The 1976 Harvard Murder That None of Us Remember

In the fall of 1976, Yale had just declared victory, 21-7, over Harvard’s football team. Following tradition, Crimson players converged in the Harvard Club for a team dinner, where the seniors made speeches. Among them was Andrew P. Puopolo Jr. ’77, referred to by his teammates simply as “Pop,” short for his last name and a gesture to his immense popularity. Described by his teammate Mark S. Taylor ’77 as “a scrappy little guy with a lot of heart,” he was “somebody who cut a wider swath than his small stature would lead you to believe.”

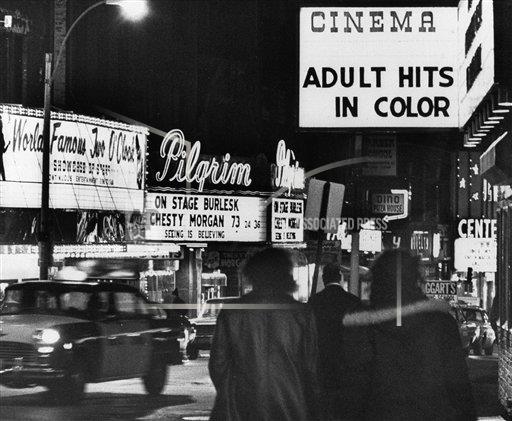

After dinner, the players set out for the Combat Zone, a nickname for what was then Boston’s burgeoning red light district, an area zoned in 1974 as a home for strip clubs, unregulated bars, and adult film theaters. Hosting dozens of thriving X-rated establishments, the area was a haven for sin in an urban fabric still soaked with the legacy of Puritanism. The events of that night — ending in a fatal encounter between Harvard football players and Zone regulars — would lead to the eventual shuttering of most of these black market businesses.

As they piled into a taxi, Michael J. Lynch ’77 recalls that “Andy was the last guy in [the car], with his leg hanging out.” He and his fellow players spent two hours at a strip joint called the “Naked i Cabaret.” They left around 2 a.m., closing time at the ominously addressed 666 Washington St. Walking to catch a ride home, a member of the team, Charles F. Kaye ’78, was solicited by a sex worker who allegedly stole his wallet. A few fights ensued between the players and the three men in the sex worker’s company — Edward J. Soares, Richard S. Allen, and Leon Easterling. During the altercation, Easterling stabbed Puopolo. Puopolo was rushed in an ambulance to a hospital where he would remain in a coma for a month. On Dec.17, he died.

Thomas J. Lincoln ’77 was stabbed as well, although he survived. He described the events of that night through an elaborate list of the factors that culminated in his friend’s death: “a chaotic mixture of unfortunate interactions between two different social cultures, questionable judgements all around, lack of clarity and understanding of the street rules in play that evening, a bit of mob-like sensibility and behavior, and a touch of tragedy in the air.”

The origins of the Combat Zone’s moniker are murky — it either alludes to the proclivity of war veterans to frequent the area or to the Zone’s high crime rates. Either way, the four-block radius of the area was legislated into existence as a response to both local priorities and national rulings. Rising crime rates, a boom in the underground sex work industry, and the city’s unique decision in 1974, just two years before Puopolo’s death, to corral adult businesses into one central location all contributed to the Zone’s creation and reputation. One central location made policing and patrolling the area that much easier. As Jan Brogan, author of a forthcoming book on the topic, puts it, the Boston Police “weren't going to be able to get rid of […] the sex shows or sex movies. So they decided to try to limit it to those four blocks.”

In a morbid coincidence, just a week prior to Puopolo’s death, a new police superintendent, Robert J. di Grazia, had commissioned an internal review of police misconduct in the Zone. The scathing report revealed what the New York Times’ John Kifner cited in 1976 as the “widespread ‘incompetence and corruption’” of the Boston Police — in one instance, it was reported that officers were given free drinks in the Zone’s bars and strip clubs, and in return allowed alcohol to flow freely with no concern for liquor licenses.

Puopolo’s death was just under a decade after the start of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Crime and only a few years after President Richard Nixon declared a War on Drugs. The media latched onto the story. The image of an Ivy League athlete falling prey to the dangers of the inner city was hard for publications to resist. A Globe column from the time illustrates the mold in which Puopolo’s story could be neatly fitted, referring to him as “a young guy whose life was going well. Young Puopolo had graduated from Boston Latin School and was playing football for Harvard, and things must have looked so beautiful until that night,” when he was “stabbed by pimps.”

Police response was equally overwhelming. Brogan recounts that directly following Puopolo’s death “the combat zone got flooded with police.” A sex worker named Corinne told the Boston Globe in 1978 that after Puopolo’s murder, “the police cracked down on us.” “‘The cops,’ she continued, ‘tightened clubs. Everything and everybody was uptight in the Zone for a long time.’” The Los Angeles Times newswire remarked in 1977 that it “began to look like a military outpost, with uniformed officers standing in pairs every 50 feet along the streets.”

While public outcry led to swift police action, the painfully slow end of Puopolo’s life made for an agonizing close to the fall semester at Harvard, especially for the football team. “It was just waiting,” Lynch describes. “Those that were religious, you know, prayed a lot.”

The mourning of friends and teammates was also met with an administrative response. A Crimson article from 2002 cites then-Dean of Students Archie C. Epps III saying, “I didn’t understand why one would go to the Combat Zone, but it had been a practice for some time.” Lynch recalls that the “silly, sophomoric tradition” of visiting the zone after the Harvard-Yale game “obviously stopped after that night.” Taylor admitted that “regretfully, we were being totally irresponsible… Full of ourselves, invincible… out in traffic.” Immediate changes in team rituals, University policy, and Zone policing in the aftermath of the murder were met by stagnation in actually adjudicating the crime, which would take two trials and many years to resolve.

The public reaction to the story was perhaps heightened by the fact that all three men implicated in the stabbing were Black, while the Harvard players involved were white. A coalition of Bostonians, including Harvard professors George Wald and Ruth H. Hubbard ’44, demanded that the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court overturn and grant retrials to the three men, noting that the prosecution was “playing up the fact that Puopolo was a white Harvard football player while the defendants were black.” Their demands were answered, and eventually upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court. Soares and Allen went free, and Easterling was sentenced to two decades for manslaughter after confessing to the stabbing.

Puopolo’s stabbing reverberated both at the University level and nationwide — yet eventually, his story stopped being told. Most current undergraduates would not know the Combat Zone existed, let alone that a Harvard student met his tragic end there. Further cementing our lack of collective memory, the Boston of that era has long since vanished: The plot of land at 666 Washington where the “Naked i Cabaret” once stood now hosts a parking garage for luxury condominiums. When asked about revisiting those same streets, Taylor expresses bewilderment: “Going back up there, I’ve wondered where the heck it was.”

— Staff writer Olivia E. Gopnik-Parker can be reached at olivia.gopnik@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @GopnikParker.