The People Who Stay

By Mollie S. Ames and Isabella B. Cho, Crimson Staff WritersNick J. Grieco moved to Boston in 2006 for his first year at the Berklee College of Music and relocated to Allston soon after. Fourteen years later, he’s still there. Even after watching friends move to other cities, he chose Allston as the place to build his network and launch his music career.

“I think my circles of friends that left before — they totally see me as the guy who stayed,” Grieco says.

Grieco stays for the same reasons that compelled him to settle in Allston in the first place: He recognized the opportunities a diverse neighborhood with a rich arts scene could offer a young guitarist early in his career. Allston, known by some as “Rock City,” has been a creative hub since the ’60s, cultivating a punk and alternative rock scene that bred the likes of Aerosmith.

But these days, Grieco is increasingly uncertain of his future in the area. “I’ve spent a lot of time setting up my roots here. But the relationship between myself and the city is really starting to feel love-hate,” he explains.

Six years ago, Grieco tried to establish an independent rock club in Allston’s Studio 52 building, but came up against city bureaucracy he feels stood in the way. Identifying a disconnect between local government and artists’ needs, he co-founded Artist Impact, an advocacy group that aims to connect artists with city resources and generally act as a conduit between them and Boston officials.

More and more, Grieco and Artist Impact have found themselves advocating for artists’ voices in ongoing real estate development plans. For some Allstonians, their livelihoods depend on ensuring development does not uproot what they see as the spirit of the neighborhood — clusters of mom-and-pop shops, collaborative creative spaces, even sweaty basement rock parties (pre-pandemic, of course).

Harvard is a major landowner in Allston, with a particularly strong presence in the Lower Allston area directly across the Charles River from its main Cambridge campus. The University has already spent over $1 billion on development in Allston, which has focused on building capacity in technology and the sciences. Other plans in partnership with private development companies involve a research campus with housing, restaurants, and a hotel.

While the community’s historic arts culture continues to attract and retain artists, many residents worry increased investment in science, technology, and commercial real estate will shift not only the terrain, but also the composition of Allston, pushing people out through rising rents.

“Right now, pretty much everybody in my shoes is fully prepared to have a rent raise that forces them out of their home and out of the city,” Grieco says.

Along with its development plans, Harvard has made efforts to support Allston through promises to build affordable housing and launching various “community benefits,” ranging from grants for arts organizations and public infrastructure, to open lectures and workshops. Some wonder, however, whether such initiatives can make up for rising housing and living costs.

The story of Harvard’s expansion into Allston has been told before, but often with the University at the center. Shifting the focus to the voices of Allston residents unearths a range of complex, often contradictory visions for the neighborhood’s future. As Allstonians ask whom development will benefit, the continuing challenge will be to ensure that the needs of the most vulnerable don’t end up slipping through the cracks.

Grieco describes himself as “pro-development,” yet that support is contingent upon Harvard and real estate developers incorporating artist and working-class voices into their planning processes. He, like residents across the neighborhood, must weigh the potential opportunity of development against an anxiety that the spaces he loves will become unaffordable, if not unrecognizable.

“I can’t help but wonder if I spent all this time on all this stuff somewhere else, how much further along the process I would be?” Grieco asks. “How much closer to achieving my goals would I be, as opposed to bashing my head against a brick wall trying to fight these developers?”

A Century in the Making

A middle-aged woman looks down from the second floor terrace of a three-decker, multi-family home, her elbows grazing a white poster that covers the entire front of the balcony. Anyone passing by can clearly read the message, scrawled in bold black script: “the BRA [Boston Redevelopment Authority] is evicting the people of No[rth] Harvard to make way for LUXURY APTS.”

Another 20 people of all ages sit defiantly in front of the building’s entrance, forming a blockade with their bodies and smoking, playing, and chatting with one another. A myriad of other signs pepper the scene, among them calls to “BAN RENEWAL ACTION” and warnings that “The Rich Get Richer and the Poor Get Homeless.”

In 1961, the BRA made plans to knock down 52 structures located on the 9.3-acre plot known as Barry’s Corner in Lower Allston, a neighborhood home to a unique community of over 70 families, many of them Irish and Italian immigrants.

Residents banded together over the next several years to oppose the BRA’s plans. While the BRA ultimately tore down their homes, their protests successfully disrupted plans to put up luxury apartments. Instead, between 1969 and 1970, the city constructed an affordable housing complex: Charlesview Apartments.

Meanwhile, Allston was steadily building its reputation as a thriving arts community and hub for diverse groups. Particularly in the ’60s and subsequent two decades, Allston attracted young artists, many of whom were college students or recent graduates, because of its public venues and affordable rents. Affordability and employment opportunities also attracted various immigrant groups — Irish immigrants in the 1850s, and Haitian, Cambodian, and Vietnamese people in the late 1970s.

This young, diverse population has only grown in recent decades. Brazilian, Chinese, Korean, and Russian communities have established roots in the neighborhood, among others. And as of 2017, 18 to 24 year-olds also comprised 41 percent of the Allston population, compared to 15 percent of Boston; 56 percent of Allston residents were enrolled in college or university.

But Allston’s appeal was never exclusive to potential residents. Real estate developers have increasingly recognized an opportunity to pursue institutional and commercial expansion in the neighborhood. In 2018 alone, the Boston Planning and Development Agency (BPDA) reported the approval of 651,000 square feet of development space. Notable projects including Allston Square and Allston Yards — which collectively span over 1,000 housing units — are positioned to transform the neighborhood.

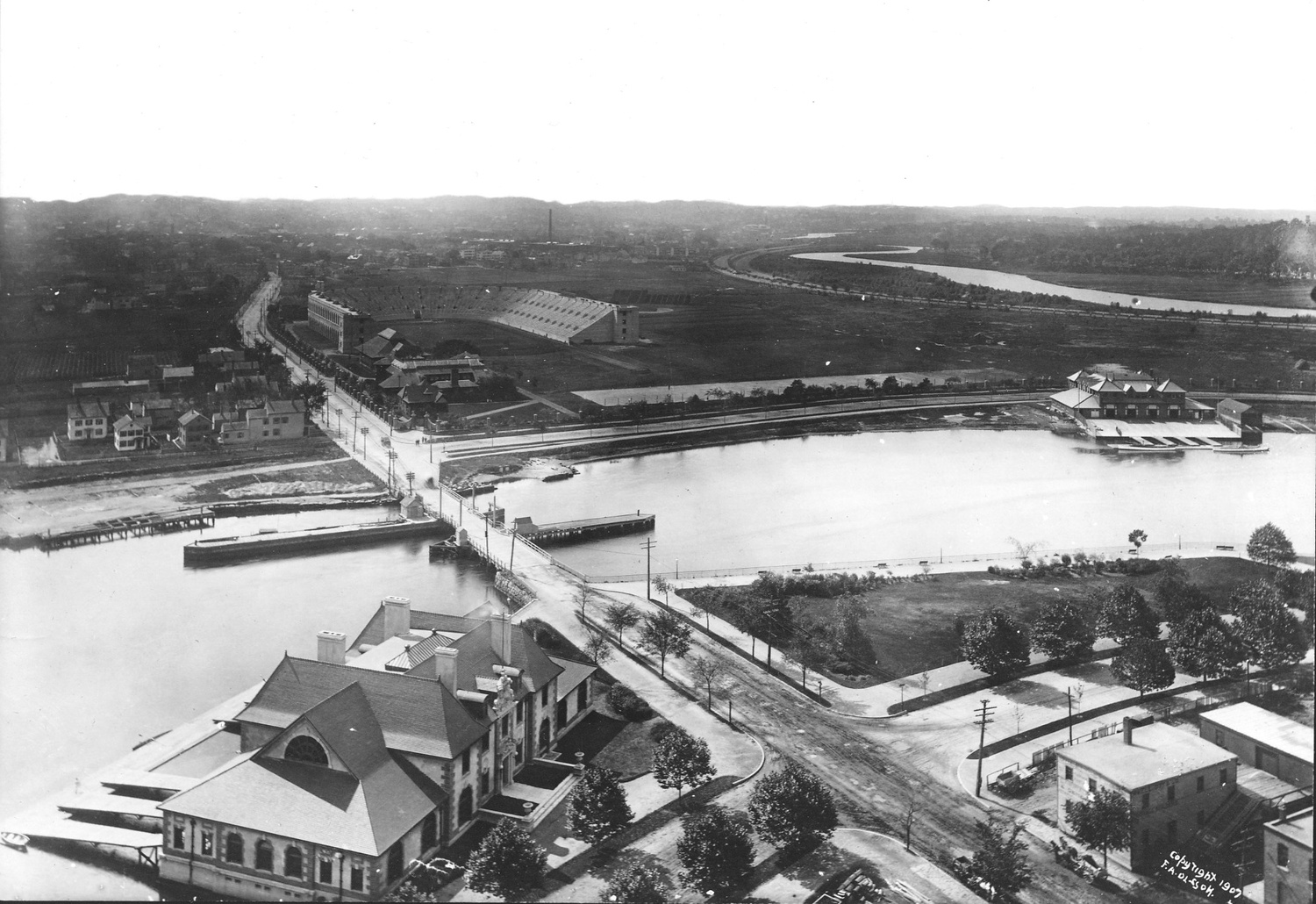

Harvard is a major player amidst the slew of developers in Allston. The University had long established itself in Lower Allston, building its athletic stadium and business school across the river in 1903 and 1924, respectively. But in 1997, the University caught some residents off guard when it covertly acquired more than 50 acres of land in the neighborhood.

“They started purchasing property under the guise of [the Beal Companies] because they were afraid that they’d have to pay a premium for the land if they knew it was Harvard University buying it,” recalls Anthony P. D’Isidoro, current president of the Allston Civic Association.

“That did not go over very well with the residents. That didn’t go over very well with Mayor [Thomas M.] Menino,” he adds. “So the relationship started in a very rocky way.”

Still, Harvard forged on in its expansion, working to mend strained community relations along the way. In 2007, the BRA approved plans for a science complex that would eventually house a new campus for Harvard’s School for Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS). Although construction on the project stalled when Harvard’s endowment plummeted during the 2008 financial crisis, the University revitalized the project in 2014. After delays due to Covid-19, the $1 billion SEAS complex was completed last month.

A year before plans for the new SEAS complex recommenced, the BRA had approved Harvard’s Institutional Master Plan (IMP), a nearly 300-page vision for the future of its growth in Allston. The IMP outlines additions to the Business School and athletic facilities, as well as an Enterprise Research Campus on Western Avenue: 900,000-square-feet of primarily office and lab spaces, in addition to living areas, restaurants, and a conference center.

That same year, the BRA also authorized Harvard’s plans for a new Residential and Retail Commons in Barry’s Corner. Harvard moved the affordable Charlesview Apartments to a new space with additional amenities down the street and partnered with developer Samuels & Associates to build a new luxury housing complex called Continuum. Today, Barry’s Corner is also home to restaurants and a Trader Joe’s.

Kevin A. McCluskey, who served as Harvard’s community relations director from 1989 to 2011, says the principle of mutual benefit was “most clearly represented” in the University’s conversations with the Charlesview community.

In anticipation of resident anxieties, Harvard made extensive efforts to address concerns over its growing presence in the area. The IMP includes a $43 million community benefits package that, among other things, would sponsor home ownership opportunities, local school improvements, and a “flexible fund” for other public enhancement projects.

“The mitigation and benefits that came out of [the IMP] have been extremely helpful in our community, and they were negotiated in good faith by both sides,” says D’Isidoro. “There’s been a lot of good things that have come out of that IMP process.”

Though Harvard’s presence in Allston looms large, the University’s identity is more complicated than many of its fellow developers. While Harvard purchases land and temporarily leases it to developers, the University itself is here to stay — so amiable relationships with its neighbors are integral for future initiatives.

With the “community benefits” outlined in the Institutional Master Plan serving as a blueprint, the University continues to devise ways of establishing trust with the neighborhood. While some residents have welcomed these partnerships enthusiastically, others doubt whether they are enough.

An “Unbalanced Confrontation”

“The artists aren’t choosing to go elsewhere,” recited BPDA Project Manager Nick Carter. “You’re kicking them out.”

Carter was reading aloud a number of anonymous comments during a public Zoom Meeting on Feb. 8 to review plans for the demolition of 119 Braintree St., a building which contains studio spaces for many artists in Allston.

Braintree Street Realty, partnered with Bracken Development, has proposed razing the current 119 Braintree building as part of a larger project to develop over 400,000 square feet into non Harvard-affiliated labs and offices, and another 86,000 square feet into residential housing.

Michael Blank, one of the landowners of 119 Braintree, assured the Zoom attendees that he and his partners have been considering the best way to protect current tenants, specifically artists, since the earliest stages of planning. “I care deeply about this community,” he said. “This is my family. I’ve been with these people for 50 years. So I’m not just looking to cast everyone aside and move on.”

Although Wayne P. Strattman, one of the 74 current tenants and roughly 27 artists with studios in 119 Braintree, says the building owners have been “wonderful,” he’s far from worry-free.

Strattman was originally drawn to Boston for its university-rich landscape. “We have, depending on who you ask, up to 60 universities here,” he says. “It’s a very educated, liberal area. It’s perfect for developing communication around the arts.”

Now, his anxiety about leaving 119 Braintree is enmeshed with a broader cultural concern. He fears that the arts are losing relevance as the neighborhood develops to accommodate ambitious STEM-centric projects — projects made possible and profitable by the very university-rich landscape he cherishes.

“The pricing per square foot for those spaces is astronomical in comparison to what artists can afford. We’re not even in the same universe, in terms of income,” he says. “What we give back to the culture is far greater, and that doesn’t compute in dollars or cents.”

For Strattman, Boston’s arts community does not merely denote a physical space, but also a shared atmosphere of collaboration and exchange. He recalls that in decades past, hundreds of people would gather in local theaters and public spaces to listen and share their work. “We built a real community,” he recalls. “But a big new biotech company is not going to do much for building community.”

“When developers come up against artists, it’s a very unbalanced confrontation. And artists are losing space all across the city,” he adds. “You can’t point to too many viable arts communities left, and what few are left are under assault.”

Concerns about affordability don’t stop with studio space. In recent years, Allston residents have witnessed a worrisome and, in the worst cases, unmanageable increase in housing costs.

Between 2017 and 2019, average rents for 3-bedroom or “family-sized” units in Allston-Brighton have risen over $600 per month, an increase of 30 percent, according to a study conducted by the Allston Brighton Civic Development Corporation. To live in a three-bedroom home, a family earning the neighborhood’s median household income of $52,795 would have to pay roughly 63 percent of their income per month.

Boston City Councilor Elizabeth A. Breadon calls housing issues in Allston “the ongoing battle.” She explains that stabilizing the cost of living in the neighborhood is critical to maintaining its socioeconomic diversity. “This has been a working-class, middle-class neighborhood for a very long time,” she adds. “And it’s very sad to see working families not be able to stay.”

Breadon is particularly steadfast about expanding the city’s Inclusionary Development Policy (IDP), which mandates that at least 13 percent of new development units are income-restricted. She would like to see new developments designate 20 percent of units as affordable.

Christine A. Varriale currently occupies one of the affordable housing units mandated by the city through the IDP. She works in the music industry and lives in Continuum Apartments, the luxury complex above Trader Joe’s in the renovated Barry’s Corner.

“To me, that’s the only reason that I’ve been able to stay in the city and live on my own and not have to have five roommates like all of my friends,” Varriale says of the opportunity to live in the building at a reduced rate.

She loves living in the building and has had a positive experience with developer Samuels & Associates, noting that they provide great service for tenants and promote public artwork. She’s not necessarily wary of new developments popping up in the neighborhood, but she hopes that going forward, as they do appear, there will be a concerted effort to include affordable housing units beyond the IDP’s stipulated 13 percent.

“Having that opportunity and making sure that other people can use that as a way to stay in Boston is important to me and [for bringing] new people who can call Boston their home,” Varriale says.

Housing advocacy is part of the reason she decided to join the Harvard-Allston Task Force, an advisory body organized by the BPDA in order to facilitate resident feedback throughout the University’s development planning process.

Varriale says she is committed to representing a new voice in the room, noting she is the youngest on the Task Force and a renter, unlike many homeowners in the group. Often, she perceives an effort among more established residents to lift up the importance of creating homeownership opportunities in Allston.

But as a young person without current plans to invest in permanent housing, she wants to refocus on the challenges of renting: “Affordable homeownership still isn’t something that I could attain, even as somebody who’s lower-middle class,” she says. “I can’t get approved for a mortgage, you know? So what good is it for me?”

For others, homeownership remains vital. Brent Whelan ’73, an Allstonian of 40 years and member of the Task Force, says Harvard’s pattern of retaining ownership and facilitating development under lease arrangements — as opposed to transferring ownership of the land — often “precludes” homeownership.

Harvard has set aside $3 million for the All Bright Homeownership Program. Through this program, the Allston Brighton Community Development Corporation — a nonprofit focused on amplifying resident voices and promoting affordable housing — purchases homes with cash to compete with investors in North Allston-Brighton, in turn reselling these homes to owner occupants.

Harvard spokesperson Brigid O’Rourke wrote in an email that the University has and continues to promote affordable housing opportunities in Allston and Boston at large.

“We are proud to continue our work with partner organizations on the front lines of addressing local housing needs and opportunities, and are incredibly proud to have helped support the creation and preservation of hundreds of affordable units in Allston-Brighton, and thousands more across the region,” she wrote.

But for some residents, concerns over homeownership opportunities persist. “Even condos can’t really be built if the landowner is not surrendering the land,” Whelan says. “This becomes a big issue for people who would like to see not a transient population, but an established community population of homeowners, and see that fostered by Harvard’s development.”

“A Good Neighbor”

Even from a distance, the sculpture resembles the shape of real coral — that is, if coral were 17 feet tall, bright white, and studded with tiny fuchsia “petals.” Closer up, however, the massive structure’s true form reveals itself: Thousands of individual laser-cut paper fragments, fastened from the inside by binder clips, converge in what is two artists’ cutting-edge visualization of “biomimicry.”

James V. Dalessandro and Jason G. Hasko are the architects behind this detailed geometric construction, aptly titled “Coralyte,” as well as co-founders of the interdisciplinary design consultancy Emergent Design. “Coralyte” was the culmination of their 30-day residency last November at Artisan’s Asylum, a non-profit that Harvard is supporting as part of its efforts to facilitate arts and community in Allston.

Artisan’s Asylum provides local artists with equipment, classes, and a collaborative workspace to facilitate their creative endeavors. It was previously situated in Somerville, but plans to transition to expanded Harvard-leased and Harvard-renovated spaces in Allston.

In November 2018, Lars H. Torres, the newly-hired executive director of Artisan’s Asylum, began a search for the organization’s next home, seeking a larger space as close to the organization’s established location in Somerville as possible. He was soon introduced to the Harvard real estate team, and in February 2020, Artisan’s Asylum signed a letter of intent to lease around 52,000 square feet from Harvard.

“Harvard stuck with us, you know? I don't know how many landlords would have done that,” he says of the University’s decision to remain in partnership with Artisan’s Asylum throughout the Covid-19 pandemic.

Recent graduates of Wentworth Institute of Technology, Dalessandro and Hasko say they appreciate being in the Boston area in part because of the institutional resources at their disposal.

“It’s all about access to tools,” Hasko says. “In Allston, there isn’t really much opportunity for somebody to walk down the street and be able to use a 3S printer or laser cutter. You have to have access to a university or have membership to more expensive shops downtown or other areas.”

While much of Harvard’s development in Allston centers on the expansion of science and engineering, Hasko believes that these goals are not mutually exclusive with the arts. Instead, he says the two can coexist in a “circular economy,” where technology finances the space and materials necessary for art, and art can help promote innovation.

The move of Artisan’s Asylum to Allston marks but one of Harvard’s initiatives to support local residents, which also include the $43 million dedicated to community benefits in the IMP.

Another notable initiative is the Harvard Ed Portal, a collaborative network that engages the local community through a slew of programming ranging from panels, career planning workshops, arts initiatives, and grants for local businesses and nonprofits. One well-established program is the annual Allston-Brighton Winter Market, an artisanal fair that allows local creatives to showcase and sell their work.

For Ross M. Miller ’77, the opportunity to partner with the Ed Portal is one of the reasons he calls Harvard “a good neighbor” to him. Miller is a longtime local artist who specializes in “landscape integrated artwork,” according to his website. A Cambridgeport resident, Miller has been based out of a studio in a building he’s owned in Allston for nearly 20 years. Through the Harvard-Allston Public Realm Flexible Fund, which funds community outreach and artists’ residencies at Artisan’s Asylum, the University has financed Miller’s current project at a park on Franklin Street in Allston.

But Miller recognizes that engaging with Harvard and its community benefits may be most helpful to those who feel comfortable enough to do so, which often entails already having some degree of privilege.

“I’ve been fortunate because Harvard seems like a familiar entity to me,” he says. “So it’s not this ‘other.’ I didn’t grow up in a triple decker in Allston and see the rents increase because people are looking to move in and work at Harvard or work in the science complex or something.”

Allston resident and tenant advocate Bonnie A. Atterstrom was interested in interfacing with the Ed Portal, but found that few of its programs and course offerings aligned with her unconventional work schedule.

“This isn’t just Harvard,” Atterstrom says. “I think universities in general forget that a lot of the times [in] the neighborhoods they belong to, the landscape of that neighborhood is very different from the landscape of a university, right?”

Miller, however, remains optimistic about the good that Harvard is doing for Allston, especially in comparison to other real estate developers in the area.

“When I look at that, rather than be upset about Harvard’s approach or the neighborhood, I go, ‘Oh my gosh, it’s really sad that that doesn’t happen in Dorchester, Roxbury, or Mattapan,’” Miller says.

He also cites some of the sustainability efforts that Harvard has made in its projects — including research on runoff water and water table replenishment — as part of what sets the University apart as a developer.

“I’m not saying that Harvard has the most perfect values,” he adds. “But I think its values are, in many cases, more progressive than other large real estate developers.”

The Journey Forward

Cindy Marchando calls her path to civic engagement in Allston a “long journey.”

“When I first came into the neighborhood, it did not feel welcoming for an outsider coming in,” says Marchando, who is originally from Trinidad and Tobago and moved to Allston in 2006. But after years of attending local meetings and making her voice heard, she came to feel that she belonged. “I had to work my way and be able to be vulnerable,” she adds, “and allow people to get to know me.”

Marchando is now a member of the Harvard-Allston Task Force, and sees her participation as a way to uplift the voices of Allstonians who may feel excluded from the decision-making process.

Marchando’s past struggles with finding affordable housing — “[I] almost got evicted from the projects because I could not even afford to live there,” she recounts — have informed her current drive to help others. “Looking at where I came from, and what I did to be able to help myself get to where I am — it’s why I’m passionate about giving back,” she says.

Other advocates for Allston’s vulnerable populations have been familiar with the neighborhood, and the University, since childhood.

“I grew up in Cambridge, and Harvard Yard was my playground. I didn’t have any context of what that meant until I went to college,” says Anna E. Leslie, one such advocate, with a laugh.

Today, Leslie is Executive Director of the Allston Brighton Health Collaborative, a public health organization focused on improving the “social determinants” of health — food access, transportation, and more — in Allston-Brighton by partnering with nearly 40 local health care providers and organizations.

Leslie perceives Harvard’s entrance into Allston as a potential opportunity to expand resources for locals — one contingent, however, upon the University’s willingness to seek out and listen to resident voices.

“A place like Allston has tens of thousands of people who already live there,” she says. “So it can’t be like Seaport; it has to be inclusive of who already is invested in that space.”

Renovating the Seaport — a neighborhood in Boston — was an expansive project that, after 10 years and $22 billion in public investment, transformed 33 acres of land into a high-end complex featuring restaurants, hotel space, boutiques, and biotech companies. Leslie says many Allstonians worry Harvard and other real estate developers will turn their neighborhood into a second Seaport, which might look shinier but would be less affordable than the historically working-class Allston.

Leslie notes that Allston has seen positive strides in recent years toward transparent communication and increased dialogue with Harvard — a trend partially facilitated by the transition to Zoom following the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as by the expansion of the Task Force. The Task Force has recently been meeting more frequently and has developed a more diverse membership. “That was a long time coming,” Leslie says. “And it was something that community members had been asking for for a long time.”

BPDA Project Manager Gerald Autler, who oversees several of Harvard’s ongoing development projects, wrote in an email that the frequency of advisory group meetings “[depend] on what proposals are being reviewed” and that in his experience many residents express concerns over there being too many community meetings, rather than too few, making it hard to attend all the sessions of interest.

Autler also emphasized that soliciting diverse perspectives remains a priority as development plans move forward, writing, “We have worked hard to dig more deeply into the population and have had a lot of success but continue to work hard at this.”

Yet for some who are struggling with food insecurity, rent, and homelessness, Marchando says civic engagement can seem pointless. She emphasizes the importance of communicating openly with these individuals, centering their perspectives, and ensuring that they feel comfortable accessing community resources, including those provided by Harvard.

She recalls her daughter’s aversion to the Ed Portal in her early years: “The first thing out of her mouth would be, ‘I would never get involved with those Harvard people,’” Marchando recalls. “Because she did not feel like that is a place for her, as a minority.”

Now, Marchando’s daughter serves as a counselor at three different high schools in the area, working to connect students with the Ed Portal’s resources. “She realized that she needed to go and bring those programs to the students,” Marchando says. Service providers need to actively reach out and communicate to residents to make such programs accessible and attractive, according to Marchando. “I think that’s really lacking in a lot of the resources that we do have,” she adds.

Jason Desrosier, the Manager of Community Building and Engagement at the Allston Brighton Community Development Corporation, describes himself as one such “liaison” between real estate developers and residents whose voices too often go unheard.

“There’s a bit of a learning curve when it comes to development meetings and community planning. If you’re a non-native English speaker, you may not feel comfortable in those spaces,” he says. While he says he often relays residents’ concerns at Harvard-sponsored meetings, his ultimate goal is for all Allston residents to feel comfortable bringing such concerns forward themselves.

Breadon, the Boston City Councilor, agrees, saying that crafting conversations in languages that reflect the ethnic diversity of the neighborhood — including Korean, Portuguese, Russian, and various dialects of Chinese — remains a pressing issue.

Additionally, despite the transition to Zoom increasing participation for some, others, particularly essential workers, have found it difficult to attend meetings during evening hours, according to Breadon.“Going forward, I think we need to be really mindful about ensuring that we do outreach to those neighbors and engage them in the process,” she says.

Whelan says he often wishes for opportunities for more substantive communication with developers and University representatives. “You reach a point which is very amicable and pleasant, but ultimately a kind of brick wall,” he says. “Harvard is cooperative with this process — they kind of have to be — but it’s not as though you can roll up your sleeves and say, ‘Let’s pull out a blueprint and talk about what would be great for us.’”

Autler, of the BPDA, wrote in an email that, although the agency is “always happy to consider ways to improve” communication processes, several avenues to collaborate and express concerns already exist, including multiple meetings and written forums for each project. He also cited Tishman Speyer’s commitment to affordable housing as an important example of how Impact Advisory Groups have been effective in incorporating community feedback.

As Grieco — the musician and co-founder of Artist Impact — contends with the complexity of the Allston development scene, he finds his mind drifting to hypothetical futures away from Boston.

Like many Allston creatives, he stands at a crossroads. It is more than a matter of growing fond of the neighborhood and its people: Allston is his home.

Despite his efforts to ensure artists’ needs are incorporated into developments that will shape the neighborhood’s landscape and culture for decades to come, Grieco admits he’s “getting tired.” He says contending with powerful developers as the neighborhood changes before his eyes can often feel like a battle of attrition.

“It’s strange,” Grieco muses, his voice colored by an ambivalence somewhere between exhaustion and wistfulness. “It’s strange to invest so much in this city, and then wonder when it’s ever going to give me something back.”

— Staff writer Mollie S. Ames can be reached at mollie.ames@thecrimson.com.

— Staff writer Isabella B. Cho can be reached at isabella.cho@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @izbcho.