Shopping for Scrubs and Other Traces of Normalcy

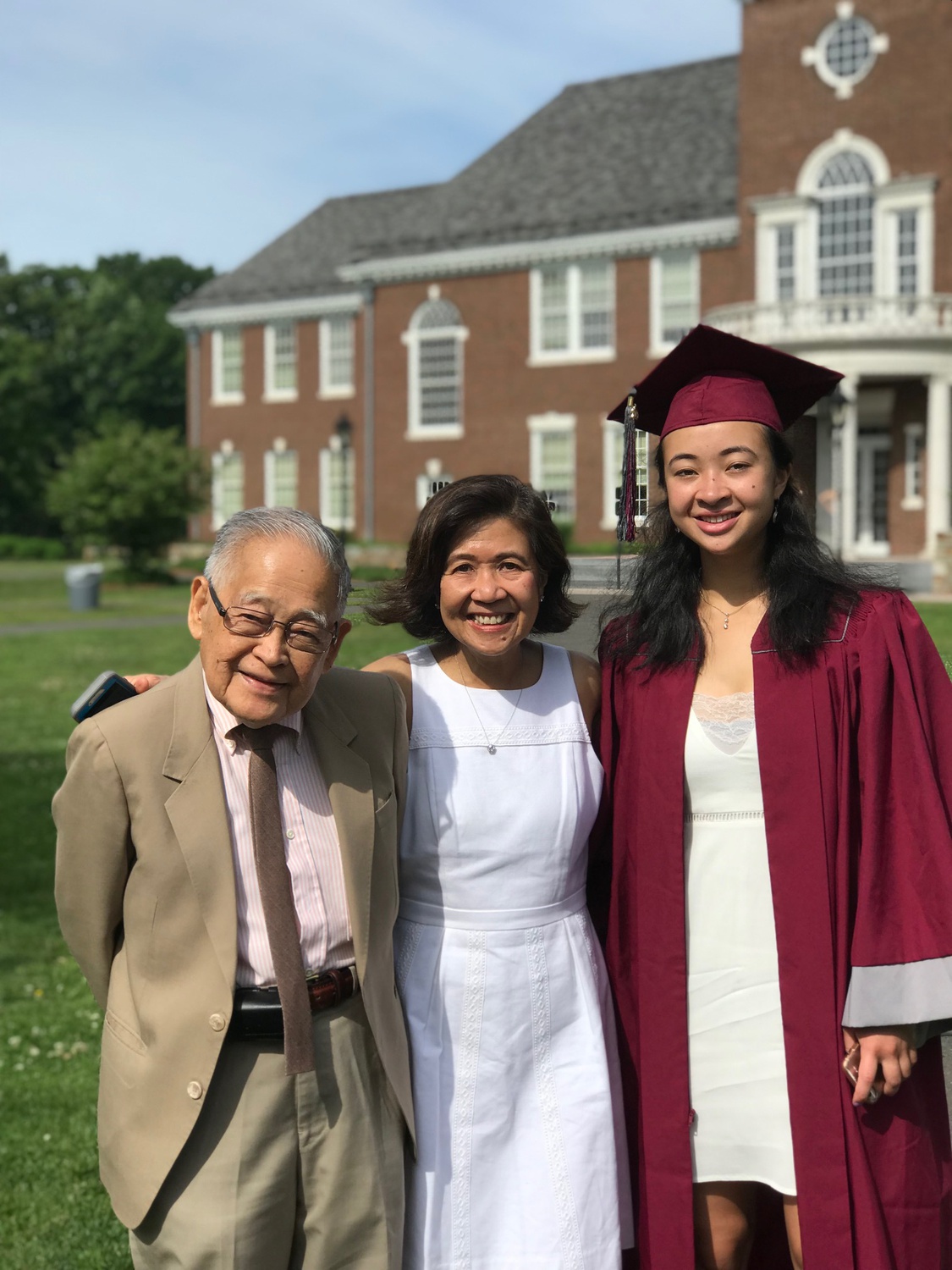

I’ve always been vaguely aware that my mom is an infectious disease doctor. There were little clues — medical jargon over dinner, horror stories about patients used to scare me into healthy eating, a skin rash-themed wall calendar — but on the whole, I simply thought of her as my mom, and beyond that, just perpetually busy.

Now, though, her profession is not just unignorable — it’s inseparable from her identity as my mom, from her very existence.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve seen the pandemic up close. I’ve seen my mother become increasingly concerned, stressed, and distant, both physically and emotionally. I’m scared.

Family dinners have migrated from the dining room to the living room. We move food from plate to mouth without looking, eyes fixed on the latest dire statistic. My mom sits in her chair to the side, blue light carving the bags under her eyes deeper.

Dinnertime is my daily news briefing. PBS provides the worldwide numbers, my mom provides the local situation. I listen, but the conversation is mostly between her and my dad, also a doctor, and the two of them speak a lexicon I can only partially understand.

N-95 — the regulation face mask all healthcare workers are supposed to wear at the hospital. Intubated — to be put on a ventilator, or more graphically, to have a plastic tube inserted into your trachea to deliver oxygen to your heart because your body can’t do it itself. Nosocomial — of an infection, to be transmitted within the hospital.

One night, my mom and I work on a Mozart piano duet. She plays primo, the treble, and I secondo, the bass. It’s been a while since we’ve done this, not since I was home for Christmas. I’m reminded of many elementary and middle school evenings spent practicing under my mother’s watchful eye, how she taught me discipline. Now, both sight-reading, we play together, apologizing and laughing when we miss a note, bumping elbows on the narrow bench.

She coughs. It’s a dry cough that cuts off the music, not just because she jerks her arms up to cover her mouth, but also because my whole body instinctively tenses at the noise. She shakes her head as if coming out of a dream, heads back to the kitchen, and leaves the piece half-finished. “We’re too close. It’s making me nervous.”

It makes me nervous, too, and sad. Lately, by necessity, my mom has felt less like my mom, more like a doctor. As the death toll rises in our state, as patients die and colleagues fall ill, she’s only become busier and more stressed. I see her only at night, when she returns from work, late, with a heaviness about her.

On weekends, when I sleep late and stretch in the sunlight, I hear my mom hurry up the attic stairs, ready to lead the daily command control Zoom meeting.

Our daily lives couldn’t be more different. I go through hours in a luxurious daze, half-present in online classes, baking sourdough, as if there’s no world beyond my front door. Meanwhile, my mom is swept up in the defining crisis of her professional career. I’ve never felt so distant from her.

One Friday, I drive up to visit my boyfriend. The weather is mockingly picturesque, all blue skies and seagulls. As I approach him, he extends his hand in a faux stop sign — as if to say: “stay six feet away!”— but then he puts down his hand and pulls me into a hug. I realize it’s been weeks since I’ve felt close physical contact.

The day is almost perfect, a sort of pre-pandemic anachronism. But as I shake sand out of my shoes and drive home, I feel a pang of guilt. My mom can’t indulge in an escape, can’t forget her role in this crisis for a second — and neither should I. Because I haven’t escaped anything, really — I’m already inextricably connected to my mom, and she to her patients and colleagues. Paradoxically, it’s because of this interconnectedness that we’ve been called to distance. When I arrive home, my mom forbids me from visiting the following week.

In the eyes of others, the connection is obvious: I’ve always been inextricably linked to my mother, now more than ever — a veritable pastor’s son of the times. I’m a conduit, both of information and of disease. “What does your mom think?” “Can my dad call your mom?” “Well, is your mom worried?” I’m spammed with requests for information from frantic group chats and concerned friends, looking for a way into this pandemic, at once ubiquitous and yet, for most, oddly far away, in news broadcasts and headlines and anecdotes. “You must have such an interesting perspective,” they say, almost enviously.

They clamor to hear my interesting perspective, or to hear from my mother directly — but only over the phone, through text, via email. I go for a run with my high school friend, taking care to stay six feet apart. Usually we stretch inside her house afterwards, but this time she says goodbye outside, hand firmly on the doorknob. “I’m sorry. My parents are nervous. You understand.”

I tell my mom about this phenomenon and she laughs, bitterly. “We’re lepers,” she says.

It’s another tragic paradox of this pandemic — healers are even more vulnerable to falling ill. Hospitals, places of recovery, can become breeding grounds for disease. Already, at my local hospital, there have been three confirmed cases among health care workers.

It’s remarkable how quickly this practice of distancing, in its physical and emotional forms, has permeated and shaped interactions, outside the house and inside. Just a couple weeks ago, my mom ate at the dinner table, sat close by on the couch, and played piano accompaniment while I sang over her shoulder. She could cleanly separate work from home — the world of white coats and patient charts from the warmth of a home-cooked meal and the touch of family. Now she doesn’t have that luxury.

At first, my parents’ discussions about the virus were charged with a perverse academic intrigue. My dad would compare the pandemic to Albert Camus’s “The Plague,” or speculate about its long-term economic impacts. My mom would talk about its epidemiological curve and transmission rate almost like a real-life word problem: If the average COVID patient infects three others, how long will it take for America’s hospital system to be overwhelmed? Justify your answer.

This academic perspective arose from another paradox: Although my parents, and especially my mom, are particularly vulnerable to the virus as doctors, they also occupy a position of privilege. They have reliable jobs, health insurance, a home to return to; they can predict the academic literature on the crisis because their socioeconomic status means they can picture stable life after the pandemic.

This post-pandemic stability is likely for our family, but not guaranteed.

These days, I brush past my mom on the stairs and hear a sharp intake of breath. I’m reminded of when I first got my driver’s permit, how she would sit in the passenger seat, white-knuckled and stiff, gasping with every lane change. A bit melodramatic, I think instinctively.

But then I remember this transmission thing works both ways: She could pick up the virus at the hospital and bring it home, but I could also infect her, and through her, jeopardize patients and other doctors. I skim the New York Times obituary page and ages of the deceased jump out at me: 75, 85, 67, 60. My mom, strong as she is, is over 60, and I can’t help but worry.

When I hear the low murmur of her 2005 Honda coming up the driveway, heels clicking to the back door, key turning in the lock — I can imagine for a second everything is normal. But I know it’s different when she takes off her shoes, sets her coat on the rack, and sits down to dinner without a word. Her end-of-the-day fatigue, always present but usually mixed with relief, now looks more like weariness. Or sometimes the purr of her car will stop in the garage, but the heel clicks don’t start for five or ten minutes. I imagine her alone in the driver’s seat with the lights out, listening to the latest figures on NPR with clenched teeth, or perhaps just sitting in the only space truly her own, in a sort of resigned reverie.

There’s little reverie to be had at home anymore. Home is no longer a safe haven from the stresses of work; the virus knows no bounds, and the home is just another possible site of contamination.

My mom’s command control meetings are all about preparedness — making beds available for the predicted influx, organizing clinical trials, ordering protective gear. But the virus is already here. In the hospital, the number of cases is accelerating. Even if my mom hasn’t brought the virus home, it’s already had a profound effect on the family.

Everything revolves around COVID. The news, the daily paper, dinner conversations. Even the small moments of joy.

We receive a package from my aunt. My mom sits on the kitchen floor in her slippers, awash in a sea of cardboard and tissue paper, like a kid on christmas morning. One by one she pulls out the gifts: Lysol wipes, face masks, Costco-sized hand sanitizer, and a box of caramel cookies. I see her weariness lift for a second: She can feel the love of family, even over a distance.

Another day, my mom calls me up to her study, smiling for the first time in days. She’s buying new scrubs and wants my advice: Should she buy aubergine or pewter, modern or classic fit? I advise her from across the room as she browses Amazon with outsized glee. In normal years, we go consignment store shopping every spring, our annual mother-daughter tradition. With a small leap of the imagination, scrub shopping is this year’s iteration. The future is uncertain, and likely dark, but we hold tight to normalcy.

— Magazine writer Maliya V. Ellis can be reached at maliya.ellis@thecrimson.com