News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

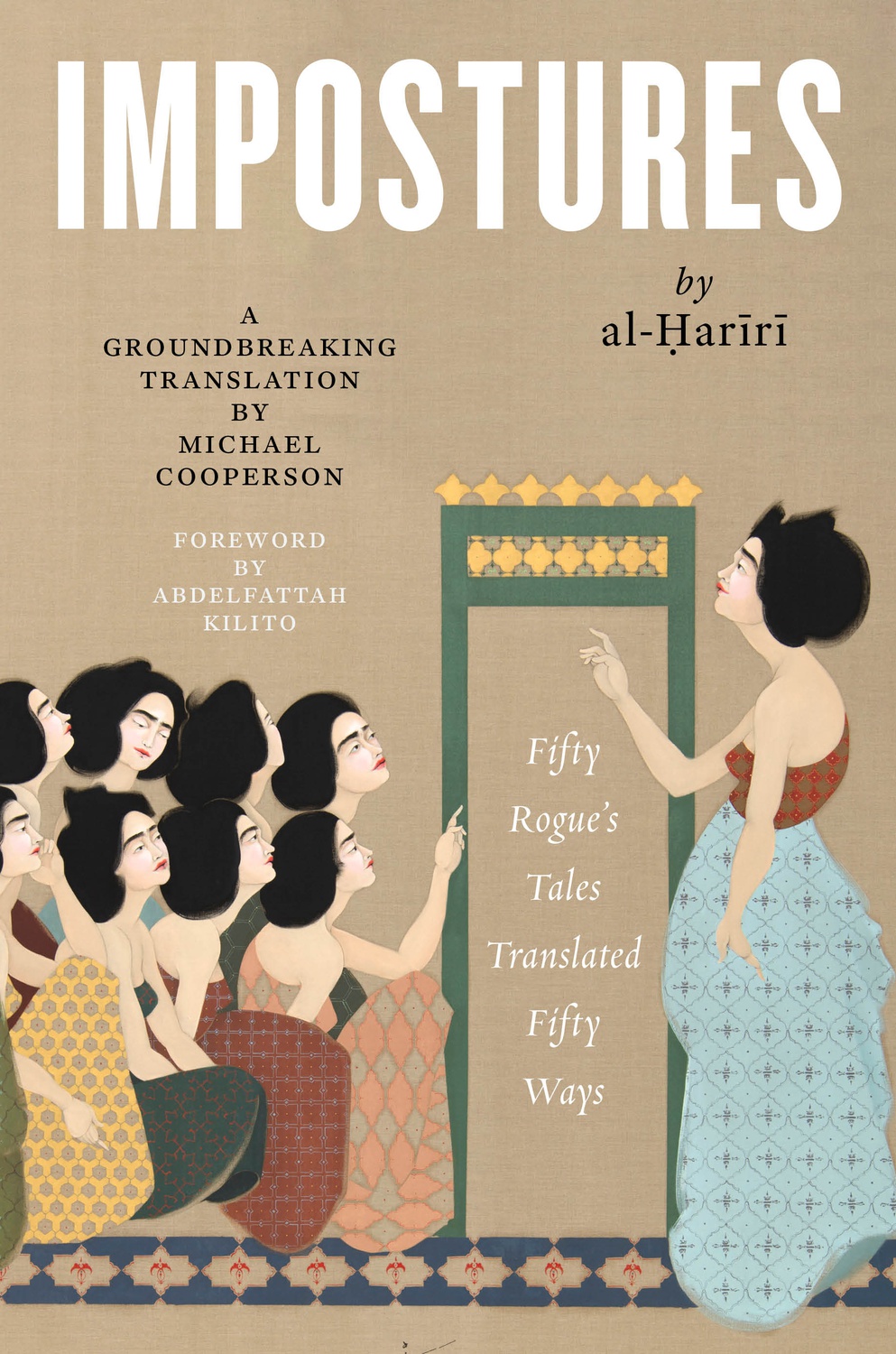

‘Impostures,’ A Literary Masterpiece In Translation

4.5 Stars

Although a crucial and intricately-crafted work of Arabic literature, al-Harīrī’s “Maqāmāt” –– set in the medieval Middle East –– is lesser known to the non-Arab speaking world. This is, in part, because many English-speaking writers have difficulty translating the linguistic intricacy and genius al-Harīrī’s “Maqāmāt” articulates. “Impostures,” as constructed by Michael Cooperson, is a new take at translating this historically and culturally-significant masterpiece.

The narrator of al-Harīrī’s “Maqāmāt,” al-Ḥārith ibn Hammām, a well-intentioned and naive traveler repeatedly encounters a man by the name of Abū Zayd throughout each of the fifty tales. Abū Zayd is an “imposture” –– as the title of Cooperson’s interpretation suggests –– posing as a different and typically penniless individual in each tale. His eloquence and way with words often fools his audience, bringing him sustenance, admirers, and coinage. It is only al-Ḥārith who eventually recognizes this trickery, usually only after he himself is fooled. Abū Zayd disguises himself behind a variety of masquerades, sometimes pretending to be a holy man, blind beggar, or victim of homicide, in order to secure the (often monetary) support of his new-found followers. Al-Ḥārith rebukes Abū Zayd for his deceit, but still treats him as a close friend.

Abū Zayd has a facility of speech that many –– including Al-Ḥārith –– admire, justifying how Abū Zayd is able to continually woo his acquaintances before he suddenly deserts them. This gift resembles Al-Ḥarīrī”s own linguistic talent. His expert implementation of many different artistic techniques, such as palindromes and constrained writing (as explored in one particular imposture in which Abū Zayd must only use undotted-letters for every second word) is truly a feat to translate from its original Arabic.

Cooperson takes a unique approach to this language problem, employing a variety of literary styles across various periods of English literature. Interestingly, he also implements other non-conventional varieties of English such as Spanglish, Singlish (Singaporean English), and even 19th century swindler lingo. In some impostures, he draws on the difficulty in comprehending some dialects of English to convey the complexities of al-Ḥarīrī’s writings. Moreover, each stylistic interpretation that Cooperson provides –– which is distinct for each of the fifty impostures –– is intentionally picked with the purpose of portraying the defining features of each tale as it was originally designed in Arabic. Nonetheless, although Cooperson expertly designs and precisely executes these stylistic choices with an incredible display of linguistic and written control, there is almost too much infusion of other literary cultures and traditions in “Impostures.”

The use of such a diverse variety of literary styles takes away from the original translation of this work of art. Although it is impossible to exactly render the precise meaning that al-Ḥarīrī intended to communicate, particularly without using the specific literary devices as originally articulated in the Arabic language, by taking from different literary traditions not related to those of the original writing, Cooperson places “Impostures” in a completely different context, leaving some readers confused. For example, by composing Imposture 10 in the style of Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales,” the tale takes on a Middle English sentiment that was not intended in the original “Maqāmāt.”

Although this can be especially disorienting for readers less familiar with Arabic and English literature from these periods, not all of the original meaning is lost in Cooperson’s translation. He is skilled at portraying the general significance and sentiment that each tale means to manifest in a unique manner that leaves readers perplexed. It is not an easy task to interpret the intricate complexities of another language that derives from a completely different culture, religion, and custom. However, Cooperson does a more than adequate job of attempting to bridge that gap.

—Staff writer Angelina V. Shoemaker can be reached at angelina.shoemaker@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.