News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

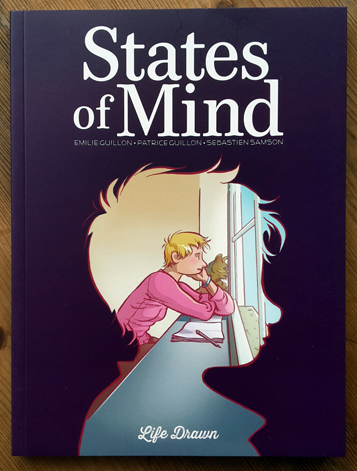

‘States of Mind’ Offers a Subtle Yet Powerful Representation of Mental Illness

4.5 Stars

“States of Mind,” is, undoubtedly, a quick read. Clocking in at about 110 pages, the graphic novel nonetheless deals with bipolarity in a way that can only be described as unflinching. Co-written by father-daughter pair Patrice and Émilie Guillon, with drawings by Sebastien Samson that seem to perfectly match the mood of the narrative, the story is told entirely in black and white — maybe it’s a stylistic choice, but it works well with the theme. Émilie, who appears as Camille in the comic, shares the many painful, intimate details of living with bipolarity. At times, it seems as though information is repeated, prompting assumptions of redundancy; one wonders, “Didn’t I already read that?” The answer is no, and that’s what makes this comic — otherwise an easily digested format — so difficult to read. The Guillon duo fully illustrates the circularity and repetitiveness of having a mental illness, showing that one step forward could lead to two steps back, over and over again.

When the story begins Camille is in Montréal with her boyfriend Julien, but soon returns home. Their separation, and his implied gaslighting, sows the seeds of the looming depression and suicidal thoughts that begin to govern her life for the next few years. One plot element largely withheld from the reader is a timeline: The story starts roughly in September 2001, and it is only near the end that another date is presented.

Camille’s journey, though chronicled through short stints in multiple facilities and six months spent working at Disneyland Paris, seems somewhat suspended in space. It’s hard to tell how much time has passed, a marker that incredibly powerful in conveying the toll mental health problems take, as well as the time needed to heal, recover, and become stronger in the face of what seems like a constant battle.

Patrice and Émilie have their own interspersed conversations throughout the graphic novel, breaking up the timeline. Through these interactions, they chronicle their decision to write a story about Émilie’s bipolarity in the first place. In these exchanges, it becomes clear that Émilie’s mental health, while much improved, is still shaky. Such a portrayal is honest: Getting better does not necessarily mean hitting a discrete point and never having to confront the problem again. Rather, it is a constant process.

The most heart-wrenching parts, are, arguably those when Camille attempts to hang herself — not confined to dialogue, these moments are shown through Samson’s illustrations — and when her mother seems to misunderstand her illness and reject her in the process. The former situation makes the abstract parts of mental illnesses real on the page for the reader, while the latter demonstrates that while support is often crucial for the struggling individual, it is difficult for family members to reconcile the illness. Yet both these moments are necessary for the story’s progression and to create an honest portrayal of Camille’s journey.

Late in the story, Camille and the reader discover that she does not have depression, exactly. Her illness is far more complex than that. Though this moment lasts for only a page, it’s striking: The doctor manages to convey to both audiences, in only a few words, how the illness manifests itself. It’s an educational moment without being obviously so.

Above all, the cyclical feeling of story likely has the greatest impact. Throughout the story, it feels as though Camille has already visited the same hospital, or seen the same doctor, or experienced the same symptoms of improvement and subsequent relapse. Such repetition is exactly the point, it reinforces the idea that working toward better mental health is by no means linear. Rather, it is an arduous process requiring time, patience, and the support of others. Even the ending itself is not decisively “happy,” precisely because there is no “end” regarding one’s health.

Perhaps one minor criticism is the perceived compression of the story: There has to be more to it, right? Such a contraction could be intended to preserve more painful details the public doesn’t need to know, but an equally plausible explanation is one that touches upon the recurring elements of the story. Were the comic to be longer, these moments, and their poignancy, would be lost. “States of Mind” succeeds not just because of its accessible format, fast pace, and dual narrative in past and present, but also because of its honesty and willingness to address a mental health issue in a way that, at times, might feel familiar to certain readers.

—Staff writer Cassandra Luca can be reached at cassandra.luca@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.