News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

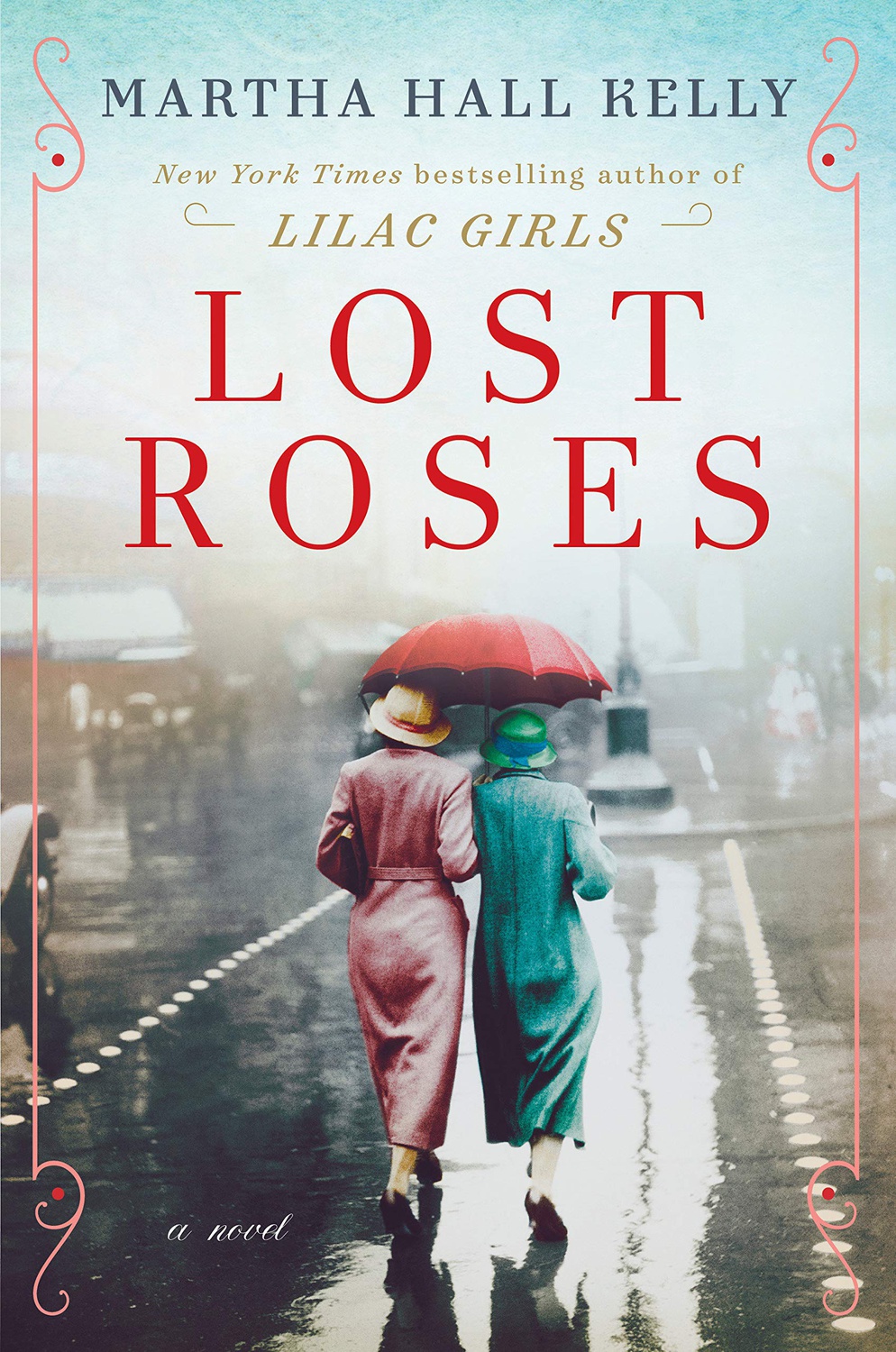

‘Lost Roses’ Brings to Life the Russian Revolution

3 Stars

Martha Hall Kelly’s “Lost Roses” weaves together the destinies of three women in an entertaining historical novel set at the brink of World War I. These women — Eliza Ferriday, Sofya Streshnayva, and Varinka — may be of different nationalities and socio-economic backgrounds, but the oncoming war is democratizing: Each must learn to survive in their own way as they face the complete upheaval of their lives.

The strength of “Lost Roses” lies in its compelling protagonists. As each woman narrates her own story, her voice and character become more distinct and moving. The portraits of these women are incredibly warm and personable, which is quite an accomplishment, considering the vast number of characters that exist within this world.

Eliza Ferriday is an American socialite and humanitarian living in New York City. Of wealthy New England stock, Eliza spends her time travelling around the world with her family until the onset of war changes her bourgeois lifestyle radically. When her best friend Sofya becomes trapped in Russia due to the war and the burgeoning Bolshevik Revolution, Eliza does all she can to aid her friend by supporting White Russian émigrées flooding into America, while also trying to track down Sofya. Eliza’s conflicts initially seem rather trivial, especially in comparison to the other women’s, yet the unexpected death of her husband Henry and building tensions between her and her teenage daughter Caroline add a lot more depth to her struggles and demonstrate just how strong of a character she really is. Meanwhile Sofya, a prisoner in her own home outside of St. Petersburg, is separated from her toddler son Maxwell and must do all she can to ensure her own survival in order to find him. She faces the most struggle, and it is her stalwart attitude which continually draws admiration. Her enduring friendship with Eliza also makes her stand out. Prone to a lack of sympathy, her love for Eliza reminds the reader just how tender she can be.

Other characters inspire just as much sympathy. Varinka is a young peasant girl who lives close to the Streshnayva estate. After the devastating death of her blacksmith father, Varinka must fend for herself and her ailing mother with the help of her father’s apprentice, Taras. Yet a stint in jail resulting from rebellious behavior has turned Taras into a cruel man who simultaneously controls, protects, and manipulates Varinka. Her job as a nanny to Sofya’s son Max initially presents itself as a great opportunity and an escape for Varinka, but with the eruption of the Revolution, she finds herself an equal to her employers at last. Though she struggles between hatred and loyalty for the Streshnayva’s, Varinka decides to take Sofya’s son, adopting Max as her own. Compared to the other women, Varinka has to grow up significantly more — but it is this arc which makes her even more interesting than the other characters.

Some of the characters, such as Eliza and Caroline, are based on the lives of real historical figures, making their stories all the more vivid. Even those who are products of Kelly’s own imagination, Sofya and Varinka, are based on diary accounts of women during this time period, formulating equally realistic characters. Kelly’s substantial research is at the core of her successful storytelling. Its sweeping images of the different cities also make use of this research, providing incredibly detailed scenes: “I urged Jarushka [my horse] along, past the captured German cannon proudly displayed in the Place de la Concorde and the Champs-Elysées and drove along the grand boulevards where the once majestic chestnut trees, thinning now, had been cut for firewood.”

While Kelly manages to captures scenes beautifully, entrenching her writing in detailed description and fact, certain big-picture elements are lacking. Though Kelly expertly inhabits the minds of each of these women, she seems to do so too effectively. It might be Kelly’s intention for the reader to experience Sofia’s naiveté in her narration, but Sofya’s committed belief to her family’s innate goodness and her belief that they are a better type of aristocrat than others is mind-blowingly naïve — to the point where her delusion is distracting. The novel doesn’t seek to be all too political, instead focusing on presenting a range of experiences, but allowing the story to be filtered through Sofya means the novel does not do enough justice to the causes of the Revolution.

The plot also relies too much on fortuitous encounters or else, reaches too far with its symbolism. This includes the roses from which the novel takes its name. Central to the story are a special breed of roses that are taken from the Ferridays’ Southampton home, which Sofya plants back in Russia. Sofya saves these from her garden while running away from the revolutionaries. Would Sofya, who is fleeing from armed men, half-starving and malnourished, really spend her time and energy saving flowers from a garden? Though they are important symbols of these women’s survival, the roses are simply unrealistic.

These kinds of issues can take away from a work that is incredibly well-researched and quite thoughtful. Even though some of the dialogue can be a bit awkward, the writing still manages to craft a profound relationships between characters. This is evident in the most complex relationship between Varinka and Sofya, which Kelly imbues with just the right amount of tension and trepidation. There are great elements to “Lost Roses,” but more often than not they are caught in the crossfire of extreme symbolism or frankly impossible coincidence.

—Staff writer Aline G. Damas can be reached at aline.damas@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.