‘Haunted by the War’: Remembering The University Hall Takeover of 1969

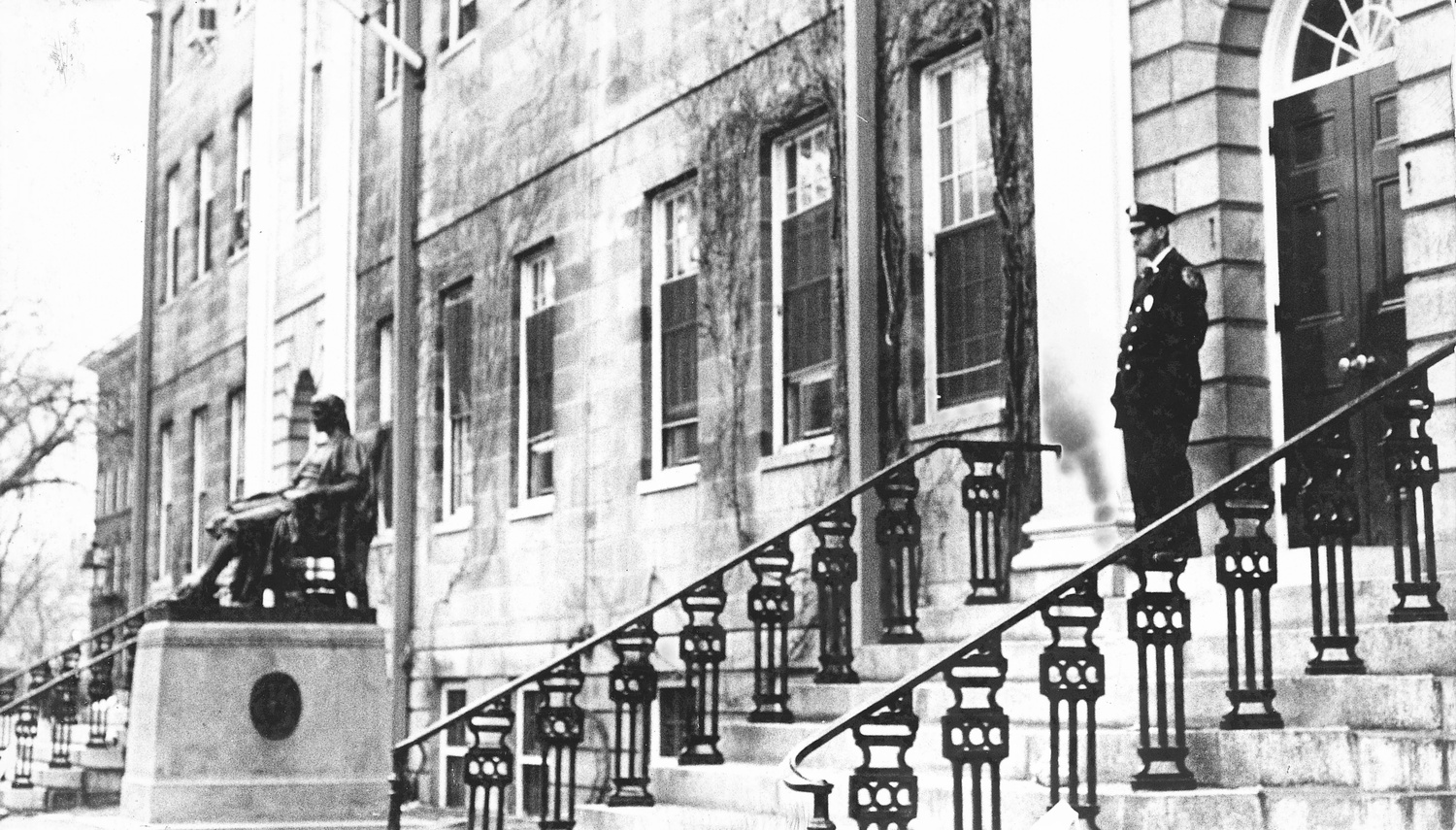

In the early morning hours of April 10, 1969, several hundred Harvard affiliates huddled inside University Hall while some 400 police officers assembled outside, prepared to storm the building.

In the early morning hours of April 10, 1969, several hundred Harvard affiliates huddled inside University Hall while some 400 police officers assembled outside, prepared to storm the building.

Former Graduate School of Arts and Sciences student Susan Schwartz Jhirad ’64 said she and other students were “rather scared” inside the building they had occupied.

“We were quite nervous,” she said. “We knew we were going to be arrested. That wasn't the question.”

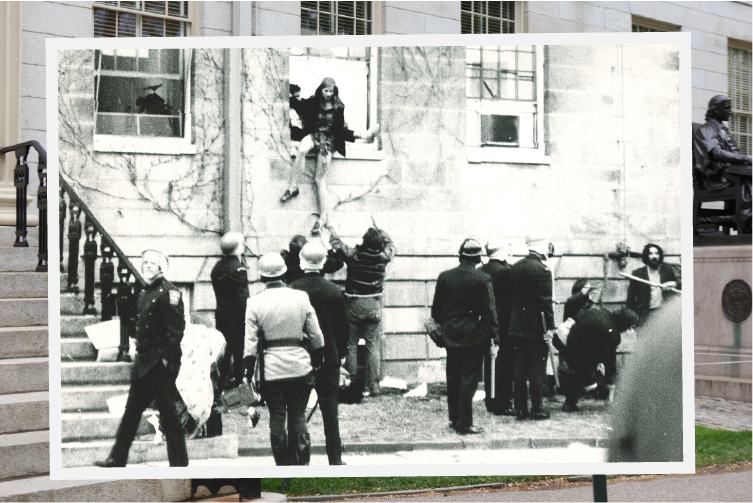

Several minutes after 5 a.m., armed with riot shields, billy clubs, and mace, the police rushed through the doors of University Hall and forcibly removed demonstrators from the premises.

The brief but violent clash resulted in between 250 and 300 arrests. Approximately 75 demonstrators and police officers suffered injuries. Arrested Harvard affiliates were rushed straight to district courts as protestors in the Yard chanted “Pusey Must Go” and “Strike, Strike” in a scene that cemented itself in Harvard’s history for years to come.

Activism Rising

The University Hall takeover was not an isolated incident, but rather the culmination of months of ramped-up student activism around local and global issues.

The Vietnam War loomed in the background of students’ lives at Harvard, according to David I. Bruck ’70 — a Crimson reporter who had been sent to cover the April occupation and raid. That anti-war sentiment permeated many of the on-campus movements at the time, he said.

“Every day was haunted by the war,” Bruck said.

In the early months of 1969, an anti-Reserve Officer Training Corps movement gained increasing traction as Students for a Democratic Society — an organization at the epicenter of much of the campus’ political action — advocated the abolition of the program at Harvard. SDS member Richard E. Hyland ’69 said the group thought the elimination of the program would have substantial effects.

“We thought if ROTC was eliminated at all college campuses across the country, that would substantially impact the number of officers that the U.S. military could recruit, and it might impact the war,” Hyland said.

The movement against ROTC — and the Vietnam War more broadly — had been brewing for months. In December 1968, more than than 100 students staged a sit-in at Paine Hall just hours before a Faculty meeting was scheduled to take place.

This demonstration forced the University to cancel the meeting, and resulted in disciplinary action to students involved. Though the Administrative Board voted to ask student protestors to withdraw from the College, the Faculty overruled that decision, instead placing 57 students on academic probation and replacing their scholarship aid with loans.

Amid rising tensions, University President Nathan M. Pusey ’28 told members of the Student Faculty Advisory Committee in March 1969 that the Harvard Corporation — the University’s highest governing body — had decided to "do everything possible to keep ROTC.” About 150 anti-ROTC students disrupted that meeting.

A month later, activists proved they had not been discouraged by Pusey’s statement. Shortly before midnight on April 9, more than 300 protesters stormed the grounds of Pusey’s home on Quincy Street.

As they marched to the president’s residence, demonstrators chanted "ROTC must go — now," and "No expansion, smash ROTC."

After some initial violent confrontation, University police officers stood down and made no further attempt to interfere with the protesters. Students tacked a list of six demands onto Pusey’s front door, which including the removal of ROTC from campus and the restoration of scholarships to the disciplined Paine Hall protesters.

Though SDS members had agreed earlier that evening to delay an occupation of University Hall, events the following day would show otherwise.

Policing Protest

Hyland said the 24 hours following the demonstration outside Pusey’s house amounted to “what may be the most important event in Harvard history.”

On the afternoon of April 9, 1969, demonstrators organized by SDS gathered in Harvard Yard sometime around noon. Organizers read out a list of demands — identical to those tacked to Pusey’s door the night prior — to the more than 100 protesters present.

And then, with chants of “Fight, fight,” the crowd flooded into University Hall. The demonstrators then demanded that Harvard administrators remove themselves from the building. Some such as Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Franklin L. Ford and Dean of the College Fred L. Glimp Jr. ’50 left peacefully while others were forcibly removed. Administrator James E. Thomas, for example, was carried out on the shoulders of one of the participants.

At approximately 4 p.m., Ford gave an order to shut the gates to Harvard Yard, and all phone lines into the building were cut off. He also told demonstrators they would be subject to criminal trespassing charges if they stayed.

The threat did not dissuade them, as demonstrators remained in University Hall. Shortly before 5 a.m. the next morning, a student arrived to warn the demonstrators that the police were en route.

Jhirad said she felt that many professors and administrators at Harvard supported the war, which motivated the students occupying University Hall to stand their ground.

“We're going to stay here and do this and get arrested,” she said, “It was civil disobedience.”

Police officers stormed University Hall using a battering ram to break down the doors and began to beat demonstrators once inside, Bruck said.

Jhirad said police officers were “really violently clubbing heads of students.”

“There were people who went to the hospital,” she said. “There are people who jumped out of windows and broke their arms.”

Pusey said that he had reached the decision to utilize the police to retake University Hall at approximately 10 p.m. on April 9 after meeting with other other administrators, including Ford and Glimp.

"It became clear in the course of the evening that the only possible alternative [to calling in police] was to take no action at all," he told The Crimson at the time.

Bruck was among those arrested by police, despite having shown press identification.

“We were all in the same lockup at Cambridge City Jail,” he said. “But I had my one phone call, and used it to call the paper and call in a report from jail.”

Though Pusey called in state police, the University’s forces wanted nothing to do with the intervention.

Robert Tonis, chief of the University Police, made his way through the crowd “apologizing” to students and pleaded to them not to try to “confront” state troopers, The Crimson reported at the time.

"As far as University Police are concerned, we didn't want to do anything about it," Tonis told The Crimson at the time. "But they're way over our heads now.”

A ‘Profound Effect’

The clash in the Yard triggered a cascade of consequential decisions in the following days and months as 2000 students voted to initiate a three day University strike later that day on April 10.

“[The strike] showed that even at Harvard, students were willing to risk their degrees and put themselves on the line to fight against the war,” Hyland said. “In other words, on that level, the goal was to try to make the country ungovernable until the end of the war.”

Jhirad said in lieu of going to clases, people would gather outside of classes to carry on academic discussions held by teaching fellows and other progressive faculty members.

The following day, the faculty voted to drop all criminal charges against the demonstrators, instead seeking academic disciplinary actions. Those arrested, however, would still be tried for criminal trespassing in May. District Court Judge M. Edward Viola found 170 of the 174 participants to be guilty.

The Faculty also voted to strip ROTC of all privileges not held by other extracurricular activities, and the Corporation endorsed that decision the next day.

The “Committee of 15” — a group charged with handing down disciplinary consequences for students involved in the takeover — announced its decisions to remove 16 students from the University while 20 others received “suspended suspension,” and 99 were given warnings.

Hyland said the consequences students faced on campus played into a larger conversation about the Vietnam War.

“Strikers played their small role in a vast tapestry of other activities,” he said. “We were trying not just to end the war of course, but to reorient the American view of foreign policy, so that we would never again be waging stupid, imperialist wars.”

He said the University Hall occupation had a “profound effect” on Harvard itself as well.

“[The occupation] jolted it out of its sleep, and forced it to try to come to terms with what education in the modern world should be like,” Hyland said.

—Declan J. Knieriem can be reached at declan.knieriem@thecrimson.com. Follow him on Twitter at @DeclanKnieriem.