A ‘Counterpoint’: The Birth of Alternative Media Outlets Amid a ‘Highly Politicized’ Harvard

The rise of protest in 1968 and 1969 gave way not only to a landmark moment for student activism at Harvard, but also to the birth of new campus publications.

The rise of protest in 1968 and 1969 gave way not only to a landmark moment for student activism at Harvard, but also to the birth of new campus publications. The Harvard Crimson — the University’s independent daily newspaper — leaned increasingly left as highly political protests ramped up on campus, prompting the rise of alternative media outlets.

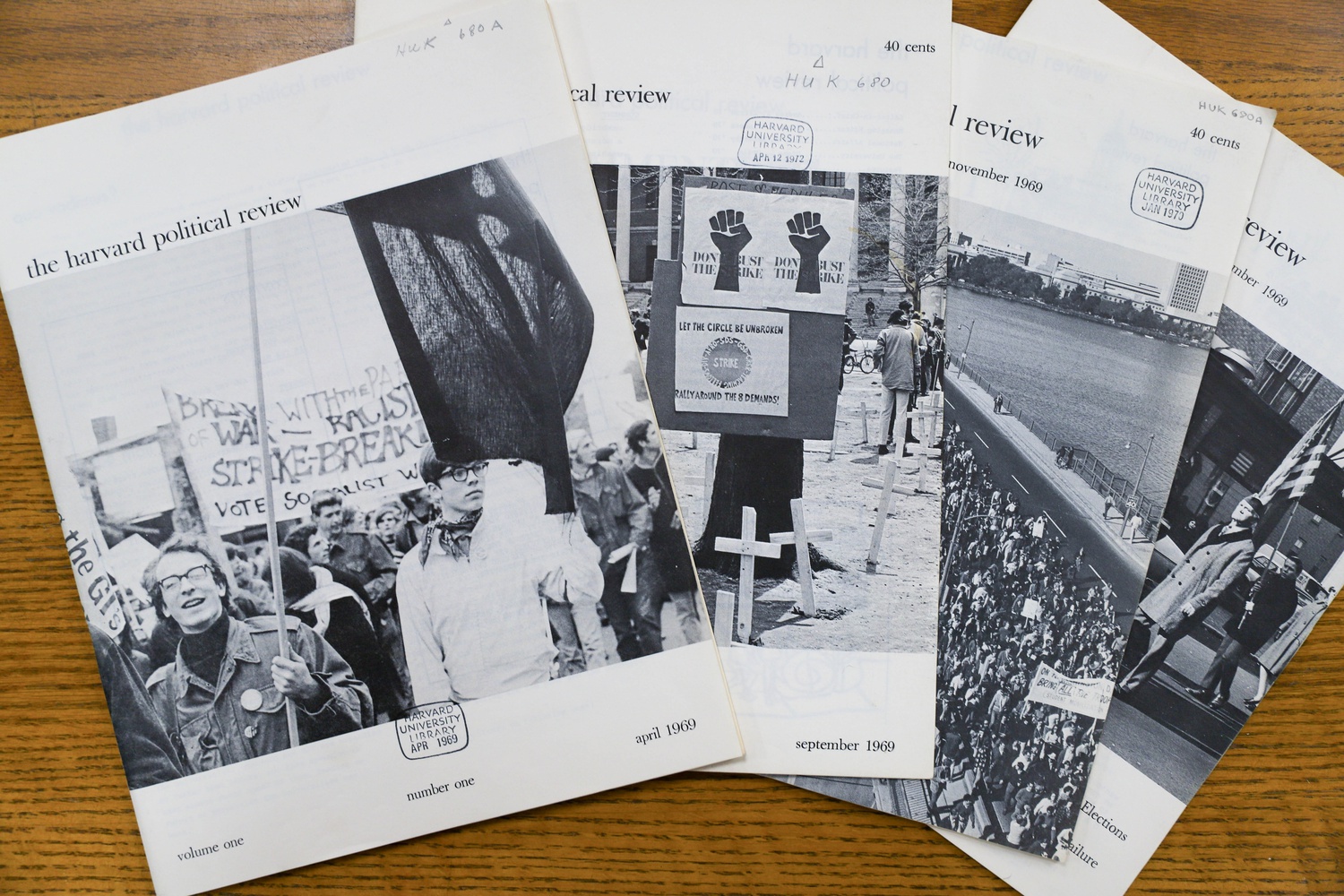

Among these outlets were the Harvard Independent and the Harvard Political Review — two student-run publications founded that academic year — and the Harvard Gazette, a publication overseen by the University’s public affairs department.

Former Crimson President James M. Fallows ’70 said The Crimson gained the reputation of being “kind of lefty” in these years. He said it was “natural” for other outlets to pop up as Harvard affiliates criticized the paper’s coverage.

Former Crimson editor Carol R. Sternhell ’71 said The Crimson had not been completely objective in its editorial decisions at the time, citing specifically the paper’s coverage of the April 1969 occupation and raid on University Hall by student protestors. Coverage of the protests — both on the news and editorial sides of the paper — heavily featured anti-administration perspectives, Sternhell said.

“If you believe journalism should be neutral, we definitely crossed that line,” Sternhell said. “I don’t remember if we ever ran a column saying why the occupation was a bad idea. We probably should’ve.”

‘It Wasn't a Game’

The fall of 1968 was a time of “extreme turmoil” both domestically and internationally, Fallows said, referencing the Vietnam War and campus protests, among other events.

Eric Redman ’70 — a former Crimson editor and Independent writer — said that Harvard’s campus was “extremely, highly politicized.”

“We had the police clubbing students. It was just a really, really politicized time, with a lot of bitter divisions on the campus,” Redman said.

Redman said The Crimson had been perceived initially as “too centered.”

“The academic year didn’t start out with the campus very radicalized. But as things went on and things occurred, it got radical pretty fast,” Redman said. “People were upset with The Crimson — they thought it was stuck in its old ways and not responding to the situation.”

Redman said the paper “tried to accommodate that [criticism]” by representing more left-leaning perspectives. “It would have been left behind, had it not veered to the left,” he added.

Sternhell said the paper’s coverage was less a response to perceived unpopularity and more so motivated by an urgent sense of responsibility.

“I remember feeling that if we didn’t stop this war, our children would ask us one day... ‘What did you do at this terrible time? Were you complicit?’” she said. “We were messianic about what was going on in the country. It wasn’t a game.”

Yet Fallows said The Crimson might have only appeared leftist to administrators and alumni. He said while the paper’s staff all opposed the Vietnam War and former United States President Lyndon B. Johnson, they did not want to take down the building for Reserve Officer Training Corps or the Center of International Affairs.

“The Crimson was — I don’t know whether it was to the left of students in general —but it was certainly to the left of the administration and to some alums,” Fallows said.

At the beginning of his presidential tenure in spring 1969, Fallows said a group called “Alumni of The Crimson and University” and the administration collaborated in efforts to rein in the paper.

In response, The Crimson assembled its own coterie of alumni — many of whom had established careers in journalism — to defend current undergraduates in order to keep the paper separate from administrative control, Fallows said. Though the effort to protect The Crimson was successful, disgruntled administration and students alike turned to other sources.

“We rallied to the graduate board to call for some alums who were in journalism to defend the students, with all the excess that students usually have,” Fallows said. “The Crimson remained student controlled, but also these other organizations arose.”

A ‘Counterpoint’

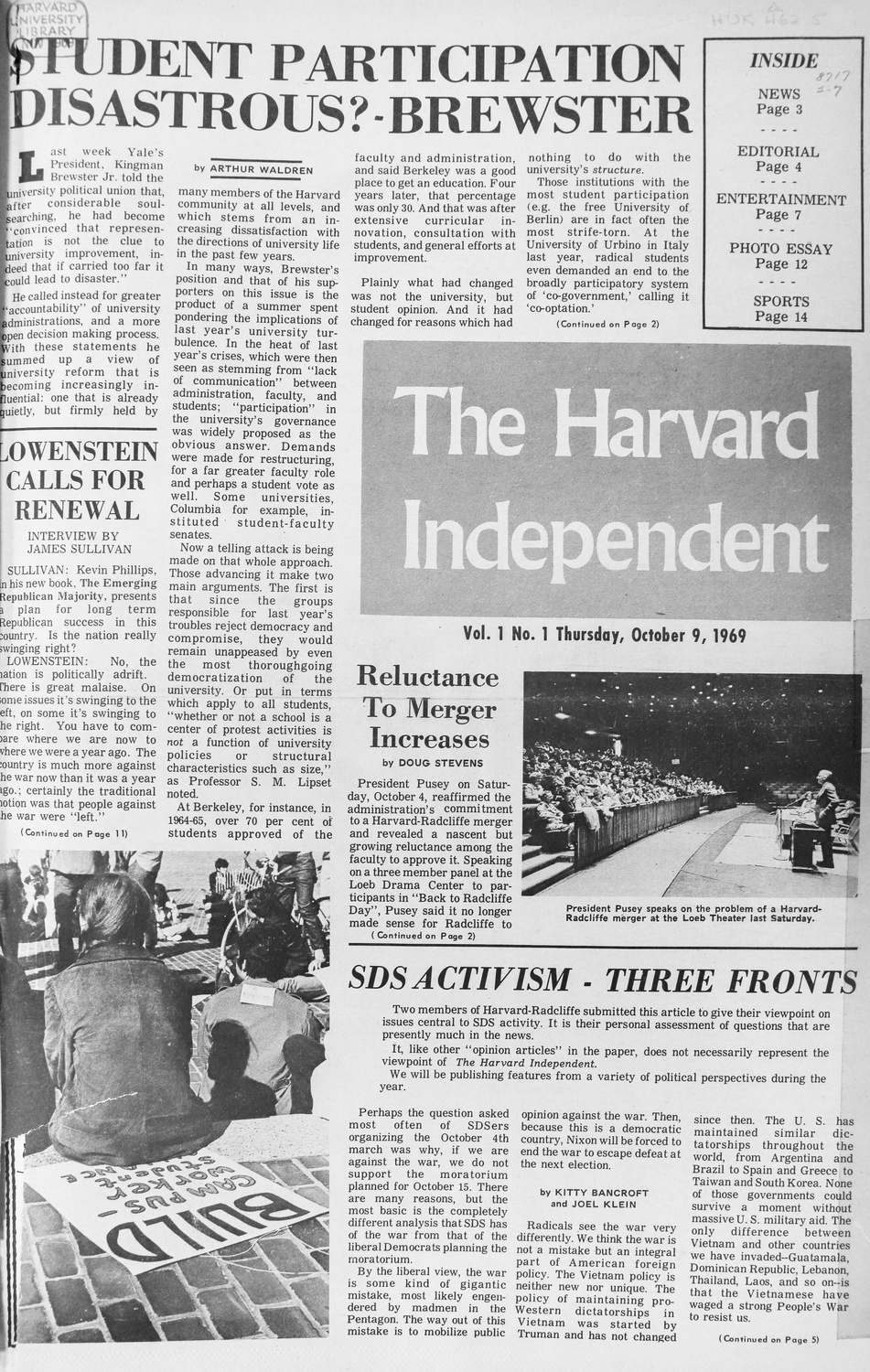

The first issue of The Harvard Independent ran on October 9, 1968, and the newly formed weekly newspaper dedicated itself to more long-form pieces from student writers than the Crimson’s daily cycle allowed for.

In its founding issue, Independent president Morris B. Abram Jr. ’71 published a letter that stated the paper had been formed to fill a “vacuum” in campus discourse and was committed to expressing “differing opinions” and covering issues with a “maximum attention to fairness and clarity.”

Former Managing Editor of The Independent Richard D. Paisner ’70, also a former Crimson editor, said the “key point” of the weekly paper was its “Counterpoint” feature — articles where two or three dissenting authors would be featured in the same piece covering the same issues.

“If you had a controversial issue, you saw multiple views of that issue. And I would say if there was a criticism of The Crimson it was that there were not multiple views, there was a right answer,” Paisner said.

Paisner said The Independent succeeded primarily because it cultivated an entirely different kind of journalism than The Crimson’s daily reporting through its more lengthy pieces.

“There was a big market in the Harvard student body for issues that deserved long thinking about and writing about,” Paisner said. “That’s the market that The Independent blundered into.”

Redman said the Independent’s conception had little to no negative impact on The Crimson.

“When The Independent started, there was more excitement about the fact that somebody had started something to the right of The Crimson than there was about anything that was in The Independent,” Redman said.

“It was something we weren’t used to seeing, but, you know, it’s a big, diverse world,” Fallows said.

Redman said though the Independent — which continues to publish weekly — was right of The Crimson, it was not a right-leaning or conservative paper.

“I would never include the word ‘right’ in The Independent,” Redman said. “All we had at Harvard was degrees of left,” Redman said. “There was really extreme left, where you would put The Crimson, then you had left, and then there was center left, which was where The Independent was.”

Meanwhile, the Harvard Gazette underwent a face lift. The Gazette — founded in 1906 — originally published a weekly calendar of events and notices.

In September 1968, the administration rolled out its inaugural newspaper version of the publication overseen by the University’s public relations department. The publishes — which still posts daily — featured stories about Harvard and its students.

Fallows said he remained unphased by the expansion.

“I think students today don’t look at The Gazette. Students then didn’t look at The Gazette,” he said.

A ‘Parallel Universe’

In April 1969, another student publication cropped up: The Harvard Political Review. HPR — founded just days before the infamous occupation of University Hall — featured political essays and was run out of the Institute of Politics at the Harvard Kennedy School.

HPR contributor Bruce C. Vladeck ’70 said the journal was the product of the newly formed IOP’s soul-searching, as the institute had been founded just three years prior.

“This was an idea somebody had to give [the IOP] a purpose, to give it a useful function,” Vladeck said.

HPR’s founding president Andrew S. Effron ’70 said he had been a member of the Student Advisory Committee at the IOP prior to establishing the journal. In a 2016 interview with the HPR, Effron said members of SAC provided feedback and recommendations to expand the IOP’s undergraduate offerings to the Kennedy School.

Effron said he asked many of his friends to write for the first edition. That edition included an essay from former United Students Vice President Al Gore ’69 when he was a student, according to Vladek.

“One of the things I remember was that one of the leading articles in our first issue was by Al Gore, and everyone was all excited that he was doing this article,” Vladeck said.

Effron said the journal was able to tap into the student discourse on wider political issues at the time such as the Vietnam War, conscription, civil rights, and the electoral campaigns of 1968 and 1970. He said this more nationally focused angle distinguished the HPR from The Crimson.

“We sought to provide a forum for articles addressing political issues at the local and national level,” Effron said. “[The Crimson] frequently addressed political issues, but as a college newspaper, it focused primarily on internal campus matters.”

On the other hand, Vladeck recalls that the publication of the HPR felt separated from The Crimson and later publications like The Independent.

“It seemed to occupy a parallel universe,” he said.

—Luke A. Williams can be reached at luke.williams@thecrimson.com. Follow him on Twitter @LukeAWilliams22.