The Island Vibe Fix

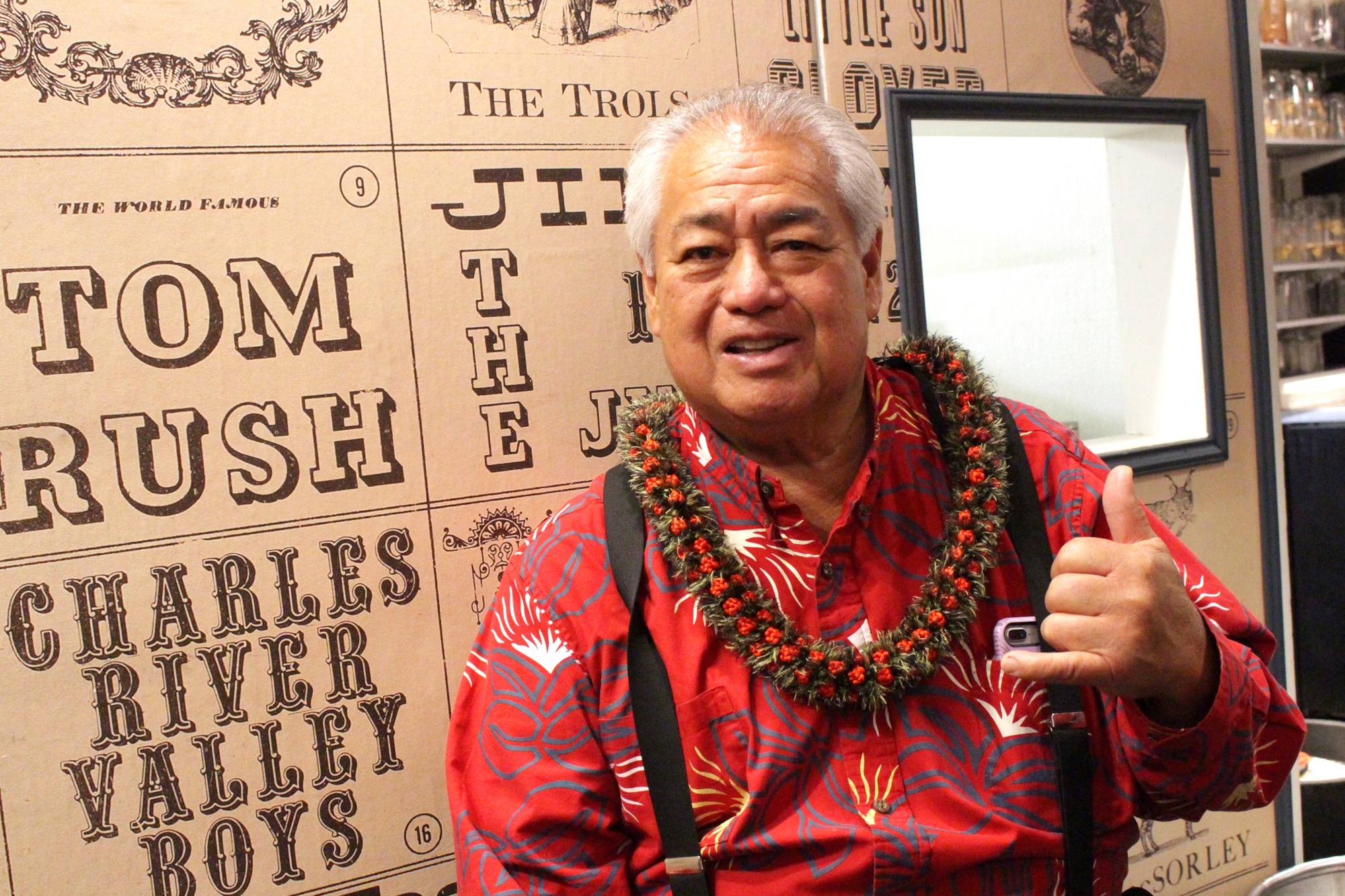

The tiny candlelit club is packed, and I have a difficult time finding a seat. Excited chatter fills the room as Cambridge residents munch on burgers and wait for the show to start. The chattering turns into cheers as a man dressed in a red Aloha shirt with a matching lei hanging from his neck trudges up to the stage. He wears a friendly smile and props open the stage door to let in some air, lamenting that, even though he’s from Hawaii, he’s hot in the crowded room. He continues to banter with the audience, making a toilet joke that is received with gales of laughter, and then he starts playing. The club goes silent as the audience freezes, mesmerized by the smooth voice emerging from such a gruff man.

This man is the three-time Grammy award winner George Kahumoku Jr. To most, he is Uncle George.

After the show, the rest of the audience files out the door. I have to fight through the crowd; I’m headed in the opposite direction. When I finally reach the stage, Uncle George smiles, wraps me in a big hug, and takes a selfie with me. It’s funny seeing him here, in the freezing cold of a Boston winter. I am used to seeing him in a tank top and muddy boots, pulling up weeds and feeding goats under the hot Hawaiian sun. He looks so out of place in cold, metropolitan Harvard Square.

How, of all places, did Uncle George end up here?

***

The last time I saw Uncle George, I was weeding his taro patch, and I was slightly unhappy with him.

Uncle George lives on a farm high up in the mountains of Maui. The drive up the mountain is terrifying, since there is only room for one car on the road, and the idea of plummeting to your death seems entirely within the range of possibility.

When my family arrived at the farm, we found everything from papayas to breadfruits to chickens to goats. Uncle George had killed six goats just before we arrived.

Through a random string of mutual friends, my family had been invited to spend a day working on Uncle George’s farm. I thought that meant we were going to feed the goats and pick papaya, which we did. But we also spent two hours weeding his taro field, laying mulch, and even spreading manure. I didn’t expect someone who sings such gentle songs to make me sweat so much.

My feelings toward Uncle George’s farm shifted slightly once the meal of ahi ahi, rooster soup, breadfruit, fruit salad, and haupia (coconut pudding) was sitting happily in my stomach. I sat to the left of some playful middle school boys, across from a woman in Alcoholics Anonymous and her sponsor, and to the right of a couple who had just moved to the area from North Carolina. We relaxed in chairs on Uncle’s lanai (porch), strumming on ukuleles like one big mismatched ohana (family).

After five hours on the farm — 7 a.m. to 12 p.m. — Uncle encouraged us to take pictures with his Grammys and then pushed us out the door so he could run to the four gigs he had that afternoon. I thanked him for the wonderful morning and hugged him goodbye. In all honesty, I never expected to see him again.

***

I was sitting in my dorm room a week ago, perusing upcoming events in Cambridge, when I came across the headline “Masters of Hawaiian Music.” It seemed so out of place on the list of local offerings that it almost felt like clickbait. I clicked it, and a picture of Uncle George popped up. I couldn’t believe that this man, so obviously an islander from head to toe, was coming to my northeastern college town. I had to go to the show.

I arrive early to interview the musicians before the show — Uncle is accompanied on his tour by Kawika K. Kahiapo and Nathan K. Aweau. I actually arrive before they do. I sit and do my homework in the empty club, feeling very much like a Type A college student and not at all like a carefree concertgoer. The men arrive and get their sound check out of the way, and then we all head into a back room of the club to chat.

I don’t know anything about Kahiapo or Aweau, so I ask them first about their backgrounds in music. As we discuss their childhoods and influences, Uncle bustles around ordering beers and burgers for the three of them.

Kahiapo tells me his father first taught him to play the ukulele when he was eight years old and slack key guitar when he was 10. His family would have jam sessions in the garage, and that’s where he was inspired to pursue music.

“Those jam sessions was like my schooling — learning the songs, learning the music, learning the chords, learning the vocals.”

The waitress hands Aweau his falafel burger as he explains to me that he started playing Hawaiian music quite a bit later in life. Both of his parents were music teachers, but they tended to play classical and jazz. It wasn’t until adulthood, when Aweau became a bass player for the legendary Don Ho — singer of “Tiny Bubbles”— that he had the chance to dabble in Hawaiian music.

“Don Ho told me, ‘You should try and write a Hawaiian song,’ so I did… and lo and behold, this song won for Song of the Year in Hawaii.”

And that’s how Aweau’s career in the Hawaiian genre began.

Learning about their childhoods gives me a sense of the Hawaiian values that inform the music they make. All three grew up in musical families, and this shaped who they became as adults. Ohana became a recurring theme in our conversation about the essence of Hawaiian music.

“Family is a big deal in Hawaii, especially in the Polynesian culture,” Aweau explains, just before the waitress interrupts us with more food.

***

My interview with Uncle George is casual, like two old friends having a conversation over dinner, with plates flying everywhere.

“To me, Hawaiian music is just part of a culture. In my life, it’s probably only about 10 percent of our culture. The other part of our culture is really living a Hawaiian life, about eating Hawaiian food, doing Hawaiian things… To eat Hawaiian food you gotta grow it. That’s how I think.”

This is why Uncle spends so much time farming, teaching, and sharing music with his local community. He tells me that he performs 20 to 30 times a week and that only two of those shows are paid. The man is busy: He gets up at 2 a.m. every morning.

We’re interrupted by a friend of Uncle’s, who brings him a ziplock bag full of homemade spam musubi — an island favorite that consists of a piece of spam on a bed of rice wrapped in nori (seaweed). My mouth starts to water.

I ask them what it’s like to play on the mainland, what kind of crowds they bring in. How is it that these musicians can pack a room when they are in a place so far their home, their values, and their culture? How does Hawaiian music translate in a place so different from Hawaii?

Kahiapo chimes in: “The real magic is that every club, every venue, every theater, every concert hall that we go to, people are drunk to come because they want the island vibe fix.”

Aweau also has an opinion on why mainlanders are so intrigued by Hawaiian music.

“Hawaiian music fans [are] everywhere... when they can hear the sound of the slack key guitar, or the ukulele, all the Hawaiian lyrics, or even just songs that describe home — the islands — it conjures up all the feeling of sunsets, moonlit nights, coconut beaches, so Hawaiian music is well-received everywhere, whether in Hawaii or on the mainland.”

What I take away from Aweau’s comment is that I am certainly not the only one with a connection to Hawaii here in Harvard Square. The rich culture that Uncle describes is received well on the mainland and abroad because people crave the feelings of ohana and aloha, which they may not feel in their everyday lives — especially not in the cold of Cambridge.

Though I am only an 18-year-old college student, and have never ever tried alcohol, I understand what Kahiapo means when he talks about people being drunk for the “island vibe fix.” As I listen to the men sing later that night, I feel something intoxicating in their voices. Their music helps me leave the stress of my day behind, and it leaves me wanting to hop on a plane and fly to Maui.

Whether people have lived in Hawaii, spent one vacation there, or even just dreamed about a visit, there is something special about the place that sticks with people. When you’re away from Hawaii, you always miss it. That’s why people come to see Uncle George and his fellow musicians. They want a taste of what they are missing.

***

As the men finish their food, I can see that they have their own little ohana on the road. When I ask Aweau who his biggest musical influence is, he points at Kahiapo without hesitation.

“When I think about Hawaii, I actually hear Kawika’s voice... I kinda think that that’s the voice of Hawaii.”

On a cold night in Harvard Square, the residents of Cambridge were able to hear the voice of Hawaii. The world is so small.

—Magazine writer Maya H. McDougall can be reached at maya.mcdougall@thecrimson.com.