Top 10 Books of 2019

10. “How To Do Nothing,” by Jenny Odell

Odell tells it bluntly: Looking at screens often happens at the expense of everything else. She asks what it would be like to observe the world more, take things in slowly, and feel present. It sounds like hippie mumbo jumbo, but for those familiar with the terms “burnout,” “Slack message,” and “action items,” “How To Do Nothing” is a strong antidote to the chaos and destabilizing feel of 21st-century life. It leans heavily on theory, but take it in slowly, as it was meant to be, and Odell’s urge to pay attention to the world will sink in even more deeply. —Cassandra Luca

9. “The Topeka School” by Ben Lerner

There’s a reason Ben Lerner’s newest semi-autobiographical novel is on the New York Times Book Review’s top 10 books of 2019. “The Topeka School” focuses on Adam Gordon, a 17-year-old high school debater and aspiring poet living in Kansas in the ’90s. Adam finds himself floating between two groups, a largely blue-collar crowd and an elite clique, during his senior year of high school. Lauded for its deft imagery and deep character development, “The Topeka School” is a thorough and fascinating look at masculinity and the power of language. —Aline G. Damas

We reviewed “The Topeka School” and gave it 4.5 stars. Read more here.

8. “The Testaments" by Margaret Atwood

This year, the world couldn’t get enough of Margaret Atwood. Although it’s been over three decades since “The Handmaid’s Tale” was published, Atwood returns to Gilead in her latest novel, “The Testaments.” In the wake of the book’s TV adaptation on Hulu, it’s no surprise that this novel generated so much buzz. Though one of several sequels to beloved favorites of the past published this year (think “Find Me” and “Olive, Again”), “The Testaments” stands out for its critical acclaim, even tying with “Girl, Woman, Other” to win the Booker Prize earlier this year. —Caroline E. Tew

7. "Black Leopard, Red Wolf" by Marlon James

Marlon James quipped that “Black Leopard, Red Wolf” is “an African ‘Game of Thrones.’” The end result, though, is anything but a spin-off. James demands readers’ attention as he introduces hundreds of characters in a world that leaves many things unexplained. The poetry of his sentences introduces Tracker, the protagonist, and begs the reader to listen to his story. That story isn’t entirely true, and James challenges readers to find where Tracker lies to save face. Overall, “Black Leopard, Red Wolf” demands more of its audience than “Game of Thrones” — and is all the better for it. —Jack M. Schroeder

We reviewed "Black Leopard, Red Wolf" and gave it 4 stars. Read more here.

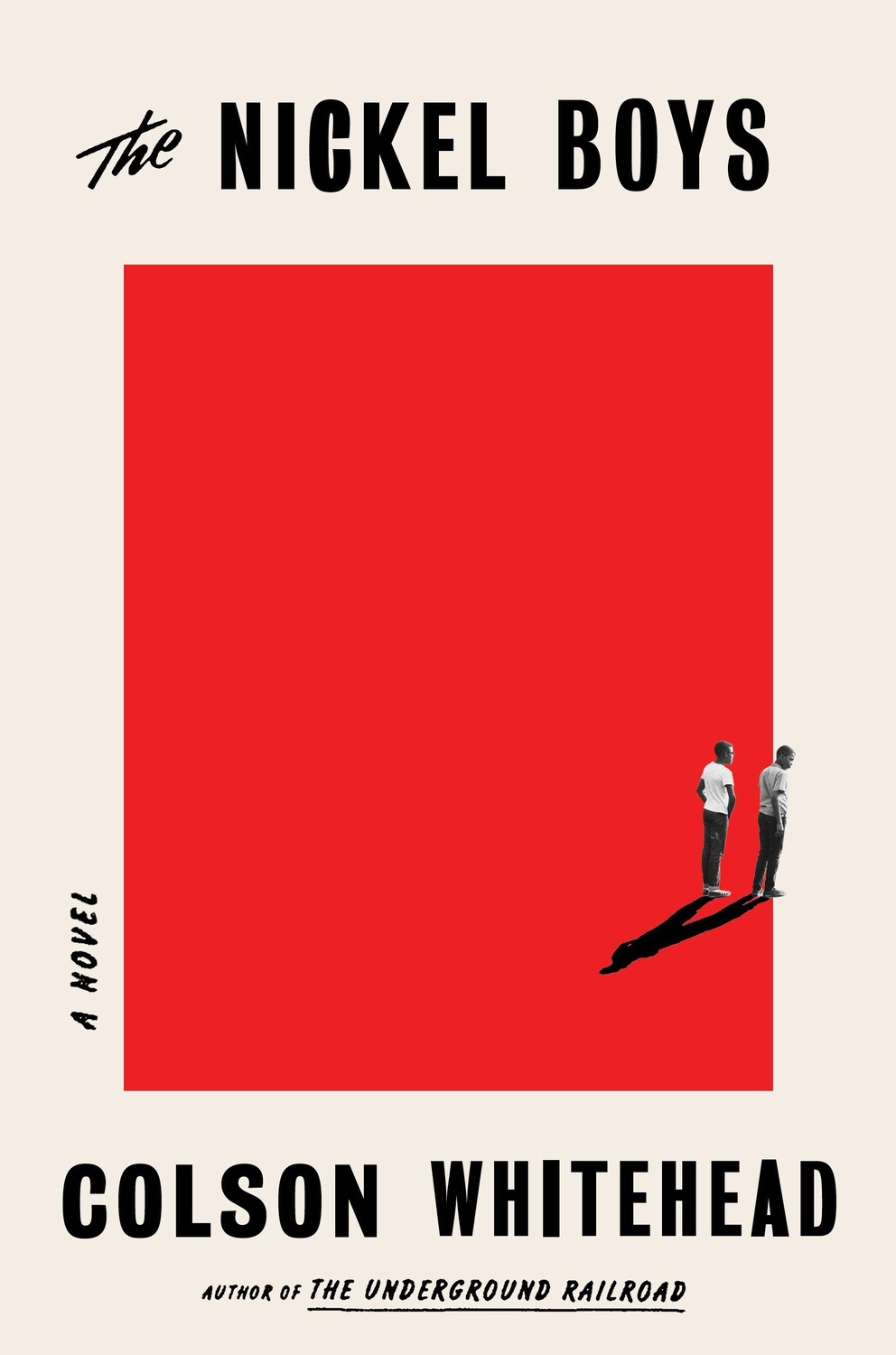

6. “The Nickel Boys,” by Colson Whitehead

“The Nickel Boys” follows the lives of young men locked away at a disciplinary institution, throwing the horrors of racism into the spotlight. The novel becomes even more discomfiting after doing some Googling: The institution in Florida on which Whitehead modeled the fictional version only closed in 2011. Whitehead’s novel is an homage to the boys who died there, and a reminder of how the past remains present. Read to the end: The twist has the effect of a gunshot. Prepare to cry and look at 21st-century America with different eyes after turning the last page. –Cassandra Luca

We reviewed “The Nickel Boys" and gave it 4 stars. Read more here.

5. “City of Girls” by Elizabeth Gilbert

Over a decade after Gilbert graced readers with “Eat, Pray, Love” comes a historical fiction novel that’s just peachy. “City of Girls” follows Vivian Morris during the 1940s as she navigates life in the NYC theater scene after getting kicked out of Vassar College, much to her parents’ dismay. Although largely focused on the years of World War II, “City of Girls” spans decades. Along with a great sense of history, this novel interrogates what it means to be a woman with sexual desires in a society that rejects exactly that. —Caroline E. Tew

4. “Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion” by Jia Tolentino

Over nine, well-syncopated essays on everything from religion to athleisure, New Yorker critic Jia Tolentino asserts herself as the preeminent bard of the raised-online generation. The 31-year-old is a bit of a wunderkind, and writes with a comforting confidence on our deep-fried digital landscape, even as she works inside it: “I don’t know what to do with the fact that I myself continue to benefit from all this,” she admits. Yet “all this” — our era’s delusions and distortions — needs Tolentino’s writing to make sense of itself. When she delivers the internet’s final exegesis, the link will certainly crash. —Amelia F. Roth-Dishy

3. “On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous” by Ocean Vuong

Poet Ocean Vuong‘s narrative prose debut takes the form of an epistolary novel: a collection of letters from a Vietnamese-American son to his illiterate mother, a survivor and emigrant of the Vietnam War. Through vignettes, Vuong explores the mother-son relationship, the aftermath of trauma, and the closeness that writing can effect, whether or not it’s read and understood: “[W]e, after all, are so close, the shadows of our hands, on two different pages, merging.” —Isabel C. Ruehl

2. “Trust Exercise,” by Susan Choi

The title of Houston, Tex., native Susan Choi’s latest novel, “Trust Exercise,” is exquisitely reflective of the book itself. A fiction novel set in a performing arts high school (like the one Choi attended) which could easily be set in the author’s hometown, it contemplates the psychological experience and trust involved in reading fiction. It exposes the ways in which it can seem that “the created world is realer than you are,” as a narrator within the text questions a fictional account of her own story. Described by The New Yorker and NPR as “thrillingly interesting” with “audacious narrative twists,” Choi’s novel simultaneously constructs and deconstructs reality. —Shruthi Venkata

1. “Normal People,” by Sally Rooney

After much buzz in the United Kingdom, Irish writer Sally Rooney — heralded “Salinger for the Snapchat generation” — became famous stateside with the publication of her sophomore novel, “Normal People.” The mesmerizing story of two Dublin university students, “Normal People” grapples with love in the time of late capitalism, specifically post-Celtic Tiger Ireland. As Marianne and Connell mature from high school to university, Rooney brings her protagonists together and tears them apart with the unforgiving frequency of natural disaster. Critics noted Rooney’s signature prose style — blunt, lucid, and conversational, it presents a modern update to the Victorian novel’s epistolary tendencies. —Caroline A. Tsai