Who Does the Celebration of Scholarships Celebrate?

By Matteo N. Wong, Crimson Staff WriterThe evening began with a cocktail hour. As waiters circulated hors d’oeuvres, Taylor and dozens of other students, all financial aid recipients, mingled with Harvard donors, some billionaires and others descendants of the namesakes of campus buildings. The students had been invited to the annual “Celebration of Scholarships,” which brings together financial aid recipients and donors.

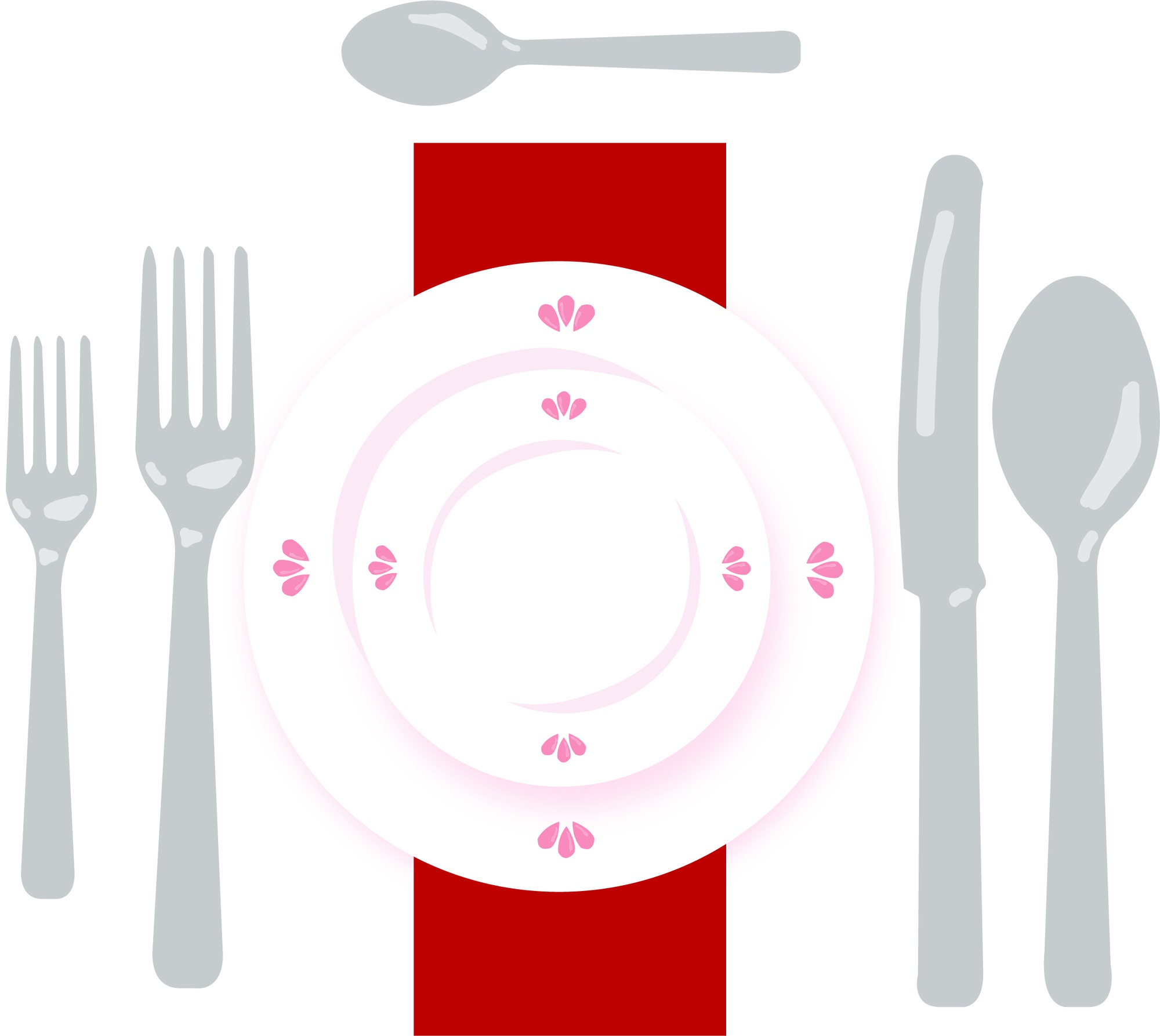

After cocktails, dividers were swept aside to reveal the rest of Annenberg, beautified with dimmed lighting, fine tablecloths, and silverware for each course — including braised ribs, pasta with mushroom sauce for vegetarians, and berry tart for dessert. “I definitely felt out of place,” Ali M. Nasser ’20 says. “I didn’t even know which fork to use for the salad.”

For some students, the opulent environment and the dinner’s nature — bringing together lower-income students and extremely wealthy donors — brought the inherent power imbalance into high relief.

“I’m on full scholarship, so knowing I’m talking to people who are wealthy enough to just donate enough money to get the scholarship named after them, and knowing that they know my socioeconomic status, it makes the whole thing uncomfortable,” Charlie recalls. Taylor and Charlie are pseudonyms; these undergraduate students spoke anonymously due to the private nature of financial aid.

The “Celebration of Scholarships” dinner has been held each spring since its creation in 2006. The event “celebrates students and the donor support that has a transformative effect on their Harvard experience,” Christopher M. Hennessy, a Harvard spokesperson, wrote in an emailed statement.

Indeed, philanthropy plays a key role in the College’s financial aid program. Approximately two-thirds of Harvard College scholarships comes from donations, and the Financial Aid Office provides more than 2,600 individual endowment funds — scholarships paid by specific donors — according to Hennessy. The Financial Aid Office is fully responsible for matching students and funds.

Fundraising requires donor stewardship, which can take the form of thank you notes and meetings between students and donors, such as at the Celebration of Scholarships. “The donors love to see all these different Harvard undergraduates who’ve gotten their money,” says Patricia Albjerg Graham, a professor emerita at the Graduate School of Education who studies the history of education and previously served as Dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

“From the donors’ point of view, having a big dinner like this is a Harvard event,” Graham adds. “They tell all their friends...‘I went to Harvard and I met the one who we’re supporting and he [or] she is just delightful.’” And, Graham adds, events such as the Celebration of Scholarships dinner encourage more donations.

Some, such as Maureen Tang ’20, enjoyed the opportunity to meet and thank their donors. “I think for me, personally, it was really cool knowing that the people making my higher education possible were real people,” she says.

Others, though not opposed to philanthropy, took issue with the dinner’s framing and execution.

“The attitude was very much like, ‘Oh, look how much we’ve helped these poor kids get out of their shitty poor neighborhoods where they weren’t safe,’” Charlie says. “‘And imagine where they would be if they didn’t have all these great Harvard opportunities they’re being offered.’ Which is really reductive to a lot of the communities first-gen and low-income students come from.” Harvard spokespeople declined to provide further comment on specific criticisms.

First generation and lower-income students benefit enormously from financial aid; they are also the only students asked to attend the Celebration of Scholarships and navigate the potentially uncomfortable social situations within. To celebrate “scholarships” is ambiguous — does the dinner celebrate beneficiaries, or benefactors? There should be a way, some students expressed, to do both; to reconcile the importance of attracting donors to Harvard with the needs and perspectives of the students whom their donations are meant to help.

‘A Brilliant Stroke’

Thomas J. Schneider ’73, who has donated to Harvard financial aid since the early nineties, first attended the Celebration of Scholarships several years ago. “It was just a great opportunity to get to know [my donees],” he says of the dinner. “There was some sharing of their stories, and also getting to hear what they were doing at Harvard, and, you know, thinking back to my own experience.”

From a modest family in western Michigan, Schneider attended Harvard on a nearly full scholarship. This act of generosity left a deep impact, and he wanted to give back.

Schneider describes the dinner as “a brilliant stroke” of fundraising — meeting donees is like “putting your name on a building” because it personalizes the donor’s gift, he says. Many donors, who were also previously on financial aid as undergraduates, are able to identify with the recipients of their scholarships, and are thus motivated to give more. Schneider says that in part because of interactions with students at the dinner, he decided to endow a scholarship at the Law School.

Though Harvard started working to become more financially accessible after World War II, it has been over the past 20 years, Graham explains, that financial aid has significantly expanded. The undergraduate student body is still disproportionately wealthy, but is a far cry from the Harvard of the early 1900s dominated by graduates of a few preparatory schools.

Philanthropy is central to making a Harvard education more accessible. “Philanthropy has helped Harvard grow the budget for financial aid from $53M in 1999 to over $200M today, and has made it possible for Harvard to increase the average award from $16,766 in 1999 to $55,750 in 2019,” Hennessy wrote.

The Celebration of Scholarships, as Graham and Schneider noted, plays a key role in facilitating student-donor meetings, which encourage donations. The dinner “is an opportunity for all who attend to learn about the many ways financial aid has a significant and lasting impact on students and the critical importance of the continued support of financial aid,” Hennessy wrote.

A robust financial aid program is undoubtedly good. “Now there’s a significant fraction of students whose families do not have the funds to support them, but students who can do well at Harvard,” Graham says. “The trick is, how do we help those students feel they are just as much a part of Harvard as the youngster whose father is the chairman of the Board and was educated at St. Paul’s after having gone to Trinity in New York?”

Schneider, when he attended Harvard, arrived “with nothing” and made friends from elite preparatory schools. “So I’m pretty relaxed in those environments and meeting the students [at the dinner],” he says.

“But there are people at the dinner who donated that, yeah, they’re not exactly the most relaxed, laid-back people,” he continues. “And if I were a student and I were eating with them, I would feel a little uncomfortable. I could definitely understand that.” The environment of the dinner, Schneider believes, depends on the individual donors involved.

The Celebration of Scholarships dinner, however, is not only made up of individuals; it is organized by an institution. The Harvard Gazette, which is published by Harvard Public Affairs and Communications, has covered the dinner nearly every year since 2014. The Gazette’s coverage emphasizes speeches that thank donors for supporting financial aid, such as former FAS Dean Michael D. Smith’s comment in 2014, “We owe a debt of gratitude to our extremely generous alumni,” or current FAS Dean Claudine Gay’s remark in 2019, addressing donors, that “This is what you make possible.”

Every year, student speakers at the dinner share their experiences struggling against adversity — including extreme poverty and oppressive regimes — prior to attending Harvard. And, every year, the Gazette’s coverage opens by highlighting one of these students’ hardships.

“The Gazette, which is partly public relations, because it goes to Harvard people, it wants to tell the most interesting stories,” Graham says. “And if the youngster has suffered extraordinarily as a child, and is now fit for Harvard, that’s a much better story.”

“Why Am I Even Here?”

Nasser was one of those student speakers, and he was featured in the Gazette’s 2019 coverage of the dinner. He explained that his speech expressed how “Harvard has expanded my horizon, and it’s all thanks to everything that they were doing, the financial aid was doing.”

After his speech, in which he discussed the ongoing humanitarian crisis in Yemen, where he was born, several donors approached him and asked if there was any way they could help. “These people really want to help and honestly, this is crazy,” he recalls.

He did experience, however, a moment of discomfort. “It just seemed like they’re saying, ‘Oh you poor child, I’m going to help you,’” Nasser recounts. “It was only for a split second I thought that, but then I got over it and I was like, ‘they’re trying to do good’” — the event, he says, was overall a very positive experience.

Many of the administrators and benefactors who speak at the event highlight the transformative nature of financial aid. In Gazette articles, donors are quoted saying they are excited to see how financial aid helps lower-income students transform the world, “going back to states or countries of disrepair, hoping to solve big problems.”

Charlie perceived this framing — “Harvard is the reason you are successful, or rather the money Harvard was able to give you” — as belittling. “[It] kind of takes out the individual agency of the student, and also kind of says, ‘The communities you came from are bad or deficient,’ which isn’t true,” they say. “There might be systemic issues and exploitation surrounding those communities, but they’re not bad or deficient.”

Taylor felt the paternalism more overtly when witnessing students of color express gratitude to a room of mostly white, wealthy donors. “It had this interesting dynamic of these very rich, very powerful, very white donors patting themselves on the back for helping these poor people of color better their situations,” they recall. “[Their philanthropy] is a good thing, but I think going about it in such a way that highlights every person of color they helped, I feel like there wasn’t a lot of self-awareness.”

Student speakers at the 2019 Celebration of Scholarships received an email early in the spring semester from Harvard Alumni Affairs and Development asking if they’d like to speak at the dinner. Nasser and Jackie Y. Ho ’19, another speaker, both said they were contacted based on the content of thank you letters they had previously written to their donors. After an interview, they were officially chosen to speak. Both Nasser and Ho said they were very grateful, and they were happy to share their stories.

For donor Sangu J. Delle ’10, student speakers’ “stories have been very powerful,” and are part of what keeps him donating money and time as a fundraising volunteer to the University. “Those dinners are really a celebration of the students, a celebration of the program,” he says. “A wonderful program that allowed me to attend Harvard — the program that is the reason I'm giving back to Harvard.”

Mikael W. Tessema ’20 attended the dinner both his freshman and junior years. His first time going, he remembers feeling confused as to why he, personally, deserved to be there.

“I was like, ‘Why the hell am I in this room?’’’ Tessema recalls. “We don’t give academic scholarships at Harvard admissions. So, why am I even here?” Part-way through the dinner, it dawned on him: “[The dinner] was specifically for fundraising and donors, it really didn’t have anything to do with anything I’ve done,” he says. “I don’t think I put that together until, like, well into the dinner my freshman year.”

When he attended his junior year, aware of the dinner’s fundraising purpose, the evening was entirely enjoyable, he says. “I actually am very grateful to my donors,” he says. “I mean, yeah, would I rather not have to perform it? Yeah, I don’t think I’d want to perform my empathy all the time, on command. But I can’t say I’m not grateful, because I am, I wouldn’t be able to do any of this without them.”

Tessema enjoyed meeting other students and his donor, hearing “juicy” details from Harvard insiders, and having the opportunity to express thanks.

Though the dinner was, in part, an opportunity for students and their individual donors to meet — students were emailed an invitation saying “the donor is planning to attend” — neither Taylor, Charlie, nor Nasser’s donor attended.

“He had a little name tag at the table and everything,” Charlie says of their donor. “So clearly he just had the social capital or whatever to decide last minute that he wasn’t going to come to this, which is also uncomfortable.” The celebration, despite personalizing fundraising, still seemed to celebrate scholarships, and their recipients, in semi-abstract terms, at times detached from the actual students present.

“As a whole it was very much centered around solely being self-congratulatory,” Taylor says. “Just sort of very happy and very content with what [donors] had done.”

Charlie believes that the dinner’s intentions were good, but its execution was lacking — which to them was indicative of how Harvard, despite pushing to recruit more socioeconomically diverse students since the launching of the Financial Aid Initiative in 2004, has been slow to accommodate those students once they are on campus.

“We’re bringing all these first-gen, low-income students to Harvard, which is good, but there’s been a lot of focus on that,” Charlie says. “And very little focus on giving those students the best resources to succeed once they’re here.”

Celebrating Students?

The Celebration of Scholarships is not the only venue in which students can meet donors. Sam, who also spoke anonymously, attended a luncheon at the Harvard Faculty Club organized by their donor with 30 to 40 students last spring, they say. “Every aspect of it was just fancier than what I am accustomed to,” they say. “So I was always kind of at a loss for how to behave.” Dean of Admissions William R. Fitzsimmons ’67 and other top Harvard administrators were present.

Before sitting in smaller groups with members of the donor’s family, Sam and other students introduced themselves in a circle. Along with name, year, and concentration, they say they felt an implicit expectation to thank the donor, and most students did.

“We were somehow, like, indebted to him and had this obligation to be there to show how grateful we were,” they say. “Which is just additional emotional labor that students from different backgrounds don’t have to deal with.”

Morgan was invited to the same luncheon, though they came away with a more positive experience. They had attended the lunch their freshman year, when the format was different — one large group instead of small tables. “I felt so much gratitude, but I felt weirdly a little bit objectified,” they recall. The large, somewhat impersonal setting, they say, made it impossible to fully express gratitude or connect with the donor. Morgan is also a pseudonym.

“Naturally in this situation, I’m being used as a prop to talk about the impact of the donation,” Morgan says. “But I’m a consenting prop in that, and I also feel like it is really necessary for students to express to donors — so that they keep donating — just how important that donation was.”

For Morgan, the group format during their sophomore year worked much better, because they were able to connect more directly with the donor’s family members. They felt that execution, not the luncheon itself, had been the problem.

Nearly every student, regardless of whether they enjoyed the Celebration of Scholarships or meeting their donor, expressed discomfort at the class dynamics reinforced by meeting wealthy donors in opulent, sometimes impersonal settings — unsure of how to speak, how to eat, or how to carry themselves, and unsure of whether people of their background and from their community belonged. A better way to meet donors, some have suggested, would be in more personal and intimate settings, chosen by students.

“If you’re asked by somebody, and what you think of as the Harvard administration, to go to a dinner — for the very reasons you don’t want to go, it’s hard for you to say no,” Graham says. Hennessy emphasized in his email that attendance at these student-donor meetings is entirely optional.

Giving students the choice to set up a meeting with their donors, Graham continues, might make them more comfortable. “Some of these young people might be very pleased to be taken out for a steak dinner. But some of them would rather say, ‘I’d like tea in my dorm.’” When Graham was the Dean of the Graduate School of Education, she regularly facilitated such one-on-one meetings; she admits that, for the college, which has many more students, this may pose a logistical challenge.

Morgan, though they enjoyed the second luncheon, also sees room for improvement.

“What’s the purpose of the event?” they ask. “The purpose of the event is to express gratitude towards donors who donated to students from low and moderate income families. So why do you have students from low and moderate income families super dressed up in a really nice setting eating expensive, nice food? Instead, what if the donors came and they did a service event with a group of students who are mutually passionate about a similar social issue?” Or attend a concert, sports game, or meet in any space the student values or regularly inhabits, they add. It was speaking with and thanking their donor that Morgan, Ho, Tang, and Tessema primarily enjoyed — not the formality of a luxurious meal.

“No one is above going to a class with a student, going to a student’s game,” Morgan continues. “If they’re going to invest tens of thousands of dollars every year, and hundreds of thousands of dollars over the course of four years, to the student’s education, I think it makes a lot of sense for that donor to engage with that student in a much more genuine context.”

And fundraising, they believe, would also benefit from more personal engagement. “Showing is much more powerful than just telling, so I think from the University perspective, it would garner a lot more financial support,” Morgan says.

At the Celebration of Scholarships, students are asked to briefly enter the donors’ world, and all the disorienting power dynamics that come with it. A celebration of students, Morgan suggests, would be a win-win, though it would require asking benefactors to, rather than meeting donees under the high chandeliers in Annenberg, immerse themselves in the worlds of their beneficiaries.

— Magazine writer Matteo Wong can be reached at matteo.wong@thecrimson.com.