News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

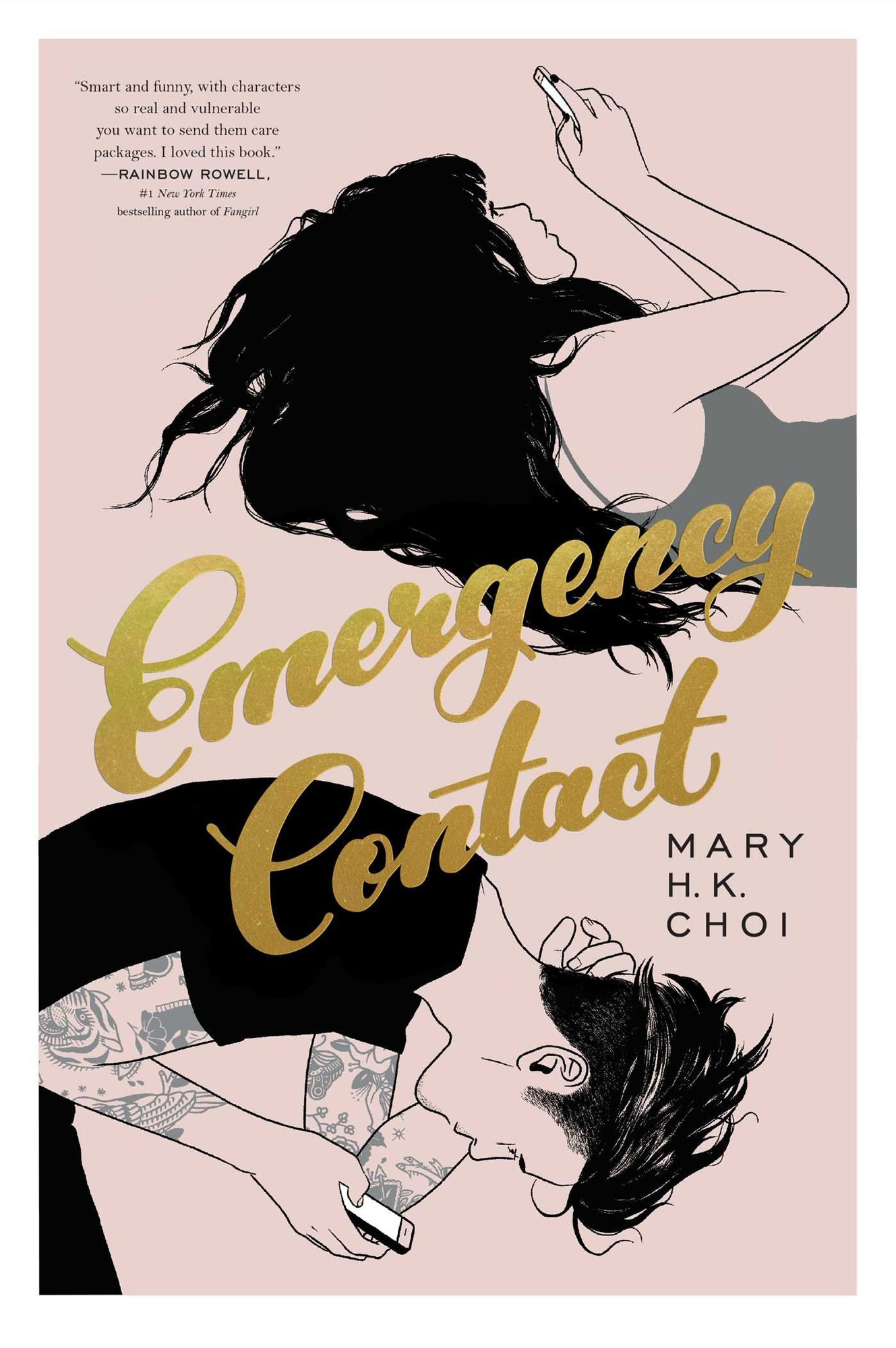

‘Emergency Contact’ Redefines Millennial Romance

3 Stars

It’s clear from the early pages of Mary H.K. Choi’s debut young adult novel, “Emergency Contact,” that Penny and Sam are perfect for each other. Penny, a freshman at UT Austin, navigates a turbulent relationship with her teenage-wannabe mother, Celeste (“the mom equivalent of a feather boa”), while Sam, a heavily tattooed 21-year-old holed up in the attic of the on-campus cafe where he works, grapples with the sudden news of his ex-girlfriend’s unexpected pregnancy. They’re obviously compatible: Both are young, both are passionate about their art (Penny is an aspiring writer, while Sam daydreams about becoming a documentarian), and both struggle to connect with people in their lives.

The twist? They rarely see each other in real life, despite being digitally inseparable and intensely codependent. Although they originally meet in person (Sam suffers a public panic attack, and Penny, coincidentally nearby, comes to his rescue), the scaffolding of Penny and Sam’s entire relationship is built and maintained via text—a romance whose unconventional narrative is starkly apparent to its main characters. “Is it crazy that we don’t hang out?” Sam texts Penny, halfway through the book. “Hang out? Like for real?” Penny replies, after some thought. “And ruin this?”

But while “Emergency Contact” purports to be a novel about romance, it’s primarily a novel about technology—more specifically, the way its integration into modern life engenders a new brand of intimacy, one whose progression is more rapid and its emotional gratification far more immediate than ever before. Choi, whose reporting for Wired includes an in-depth look on the way teens use social media, has a finger to the pulse of millennial psychology: When the book’s prose does not explicitly report Penny and Sam’s text-lingo-laden conversations, it’s propelled by a particular adolescent energy, one fraught with the anxieties of self-discovery and romantic tension. Who texts first? How frequently? What’s too personal to be revealed, and when does it become acceptable to reveal it?

Though its prose is occasionally stilted, “Emergency Contact” hums periodically with life. Like text message notifications, the book’s spasmodic vibrations have the complexity of emoji-laden missives. What’s left is a freshly postmodern conceit, conveyed in a sweet, albeit simple, parable about the virtues of virtual love and the politics of desire in an evolving technological landscape.

The young adult genre tends to hem in Choi’s prose; the novel’s conversational syntax is accessible, almost to a fault. At risk of going over her (likely teenage) readers’ heads, Choi explains pop culture references. It’s not enough to say “rumspringa” and expect comprehension. Instead Choi resorts to “rumspringa, that rite of passage for Amish people.” Imelda Marcos becomes “Imelda Marcos, the kleptocrat wife of the former president of the Philippines who had hoarded three thousand pairs of shoes while her people starved.” Verbosity blunts impact. At times, the degree of separation between Choi’s adult voice and Penny’s adolescent interior one becomes palpable, and the inhabitation of the teenage voice a more apparent (and inauthentic) construct, particularly in its hyperbole. “Penny would rather eat a pound of hair than reveal her true emotions,” Choi writes in the book’s opening pages; later, Sam “briefly [considers] rolling into a ball and ugly-crying for the rest of the day,” and still later, Penny “could practically hear the AWWWWWWW in her head and Care Bear stares flying out of her eyes.” Free indirect narration operates inelegantly: Penny and her friend, Mallory are “two giggly girls with great big hair doing irrepressibly fun things,” a descriptor that reads unfurnished, like screenplay direction.

But for what it lacks in style, “Emergency Contact” makes up for in substance. Its narrative is most potent when it’s unclean, especially when Choi pays masterful attention to the messy parts of Penny and Sam’s lives. Penny’s evident social anxiety and smarter-than-thou cynicism and Sam’s all-too-real reckoning with depression and poverty lend each respective character a certain roundness. Supporting characters, though perhaps initially stock figures, grow into their roles: Celeste’s frustrating immaturity evolves from a plot device into a complex character flaw, while Penny’s rich-bitch roommates wield their privilege and status in unexpectedly benevolent (and surprisingly, un-patronizing) ways. Choi also gestures at socially valuable conversations: There’s one about race, one about class, and one that comes late in the novel about affirmative consent.

Perhaps her most valuable conversation, though, is not about technology or love or race at all. It’s the one about what it means to be an artist in the world, and this is the most urgent undercurrent of the novel. Sure, Penny and Sam have chemistry with each other, but their real chemistry—not to mention, the foundation of their interpersonal connection—is with their art. Or as Bastian, the 13-year-old subject of Sam’s documentary unwittingly conveys the book in microcosm, “It’s fucking art, man. You don’t choose it. It chooses you. If you waste that chance, your talent dies. That’s when you start dying along with it.” If that’s not love, what is?

—Staff writer Caroline A. Tsai can be reached at caroline.tsai@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @carolinetsai3

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.