News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

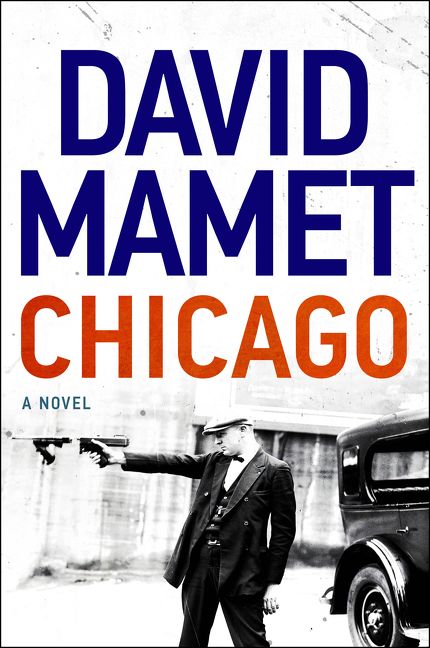

Mamet Successful Again with ‘Chicago’

4.5 Stars

“Jackie Weiss, Mike Hodge wrote, had died of a broken heart, it being broken by several slugs from a .45,” reads a line in “Chicago.” In his new novel, Mamet interweaves Mike Hodge’s love story, journalism career, and a city’s intricate Prohibition politics with witty dialogue and captivating details.

For his first novel in two decades, Pulitzer-winning author Mamet goes back to his own hometown as the setting for a complicated plot. Mamet dives into 1920’s Chicago with Al Capone’s gangs in the South, the Irish up North dispersed through the police ranks, the Jews who find themselves caught (and killed) in between, and, of course, the world of Hodge and his colleagues: the newspaper.

The archetypal hero of the story, Mike Hodge, leaves his home to fight in the First World War as a fighter pilot. He returns and settles down in Chicago as a journalist for the Tribune when he falls in love with Annie Walsh, an Irish girl more closely involved with his reporting sources than he could have guessed. Hodge’s tragedy strikes when Walsh is shot dead in his own apartment in front of his eyes, leading to a quest to find the person who killed the love of his life. His ruthless aim, along with his pain and thirst for revenge, drives his professional need to pursue the next lead, the next great story of crime to report for the paper.

As with any good crime story, “Chicago” is full of twists and surprises. The novel’s supporting characters develop as equally well as the lead characters. Amongst them is Hodge’s fellow veteran, colleague, and often accomplice, Clement Parlow. Parlow provides a contrast in humor and heart to Hodge, driving some of the novel’s best dialogue. One would expect no less from Mamet, a seasoned and renowned playwright.

Their conversations take place in settings spread throughout the city that Mamet returns to again and again, establishing familiarity. In a sense, each scene feels like the cuts of a play, as Mamet turns a stage experience to paper. There’s the City Room, the office where Hodge and Parlow write their stories, where Parlow constantly yells for the copy boy. There’s Mike’s apartment, of which readers see glimpses during Mike’s flashbacks of Annie in his room. There’s the Budapest Cafe, “a luncheon resort, sufficient superior to a coffee shop or lunch counter to appeal to the genteel, the shabby-genteel, and those who enjoyed, or did not mind, their company,” where Hodge often brings Annie during their “courtship.” There’s the Ace of Spades, a whorehouse run by Peekaboo, Hodge’s friend who knows the ins-and-outs of the city thanks to the powerful men who come through and the love affairs they bring with. The list goes on, each place holding a myriad of stories.

Even as a bystander writing about the crimes in the city, Hodge follows the “principle” of the City Room, where the reporters “felt themselves entitled to whatever copy they could convert into preference, sex, or cash.” Mamet crafts the tales and experiences of these journalists cleverly, exposing their own struggles for a claim to fame underlying their everyday struggle to get the new scoop in an age of corruption. Other ’20s era sentiments shine through in the immigrant divisions deeply entrenched in the metropolis, the racial segregation not yet questioned, and Hodge’s sexist love for Annie, lusting to “wife” her into a stay-at-home mother.

As Hodge pushes on with his own investigation, he realizes that his own attempts to link murders amidst the violent powerhouses of the city aren’t enough to uncover the truth. His discovery is dark enough to become the next exposé of the paper, but Hodge has no intention of writing that story. Instead, he seeks revenge, even though he “had not fired a handgun since France.” The answers to Annie’s death aren’t particularly important, but Mamet’s ending is nonetheless powerful.

With humor sprinkled amongst even the most dire of situations, Mamet’s “Chicago” is an engaging read. The characters draw readers in, while Mamet’s narratives on the settings in the city vividly connects them. Mamet’s new novel is a treasure, a piece of fictitious history entrenched in an era of violence and love.

—Staff writer Lucy Wang can be reached at lucy.wang@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @lucyyloo22

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.