From Fortune 500 to the Freedom Trail

Gary A. Gregory arrived at Faneuil Hall dressed in blue jeans and a black baseball cap. Ten minutes later, he returns wearing a homemade apron, mustard-brown waistcoat, white stockings, and tiny, nose-pinching spectacles. “Now I’m Superman again!”

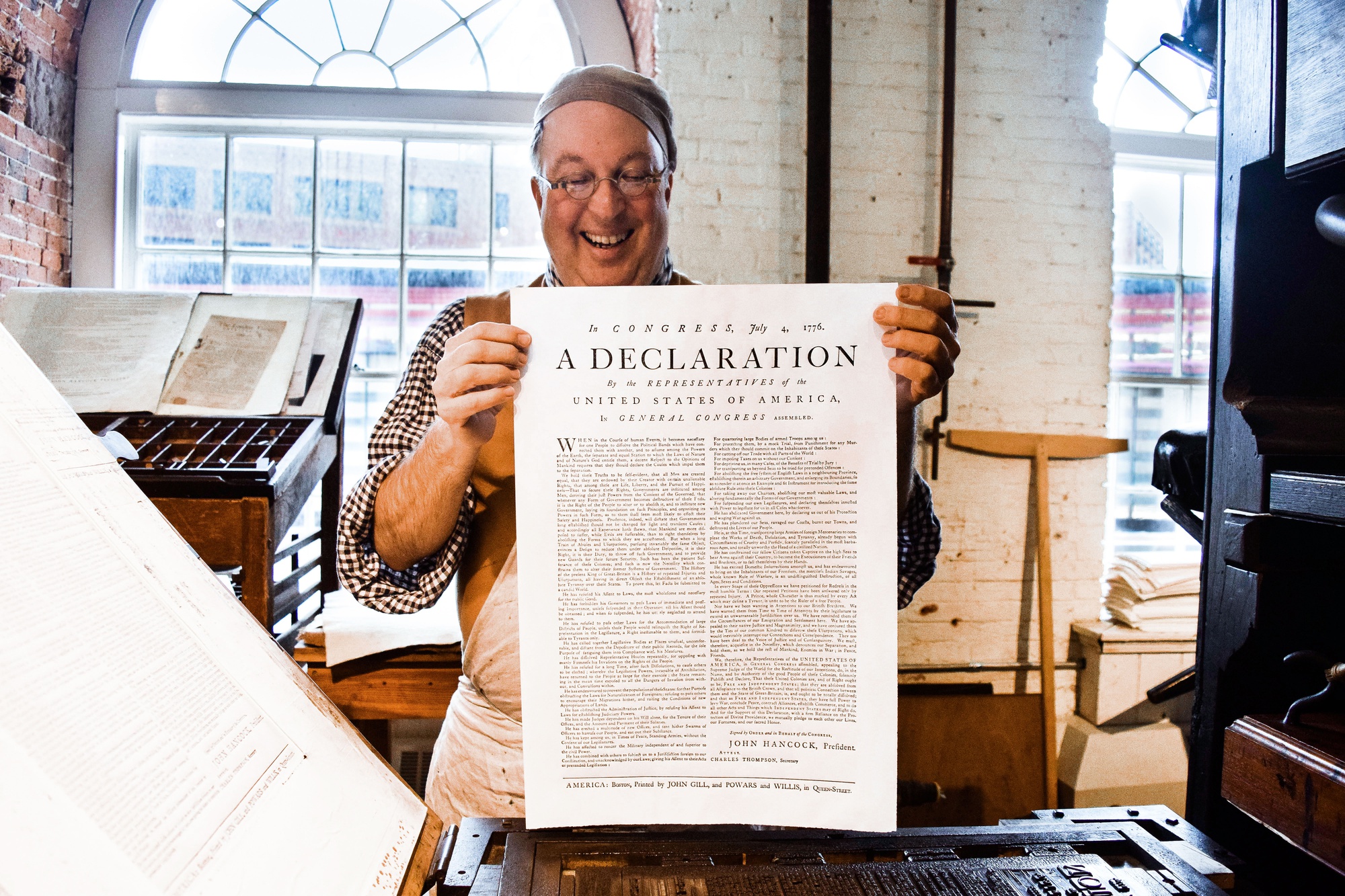

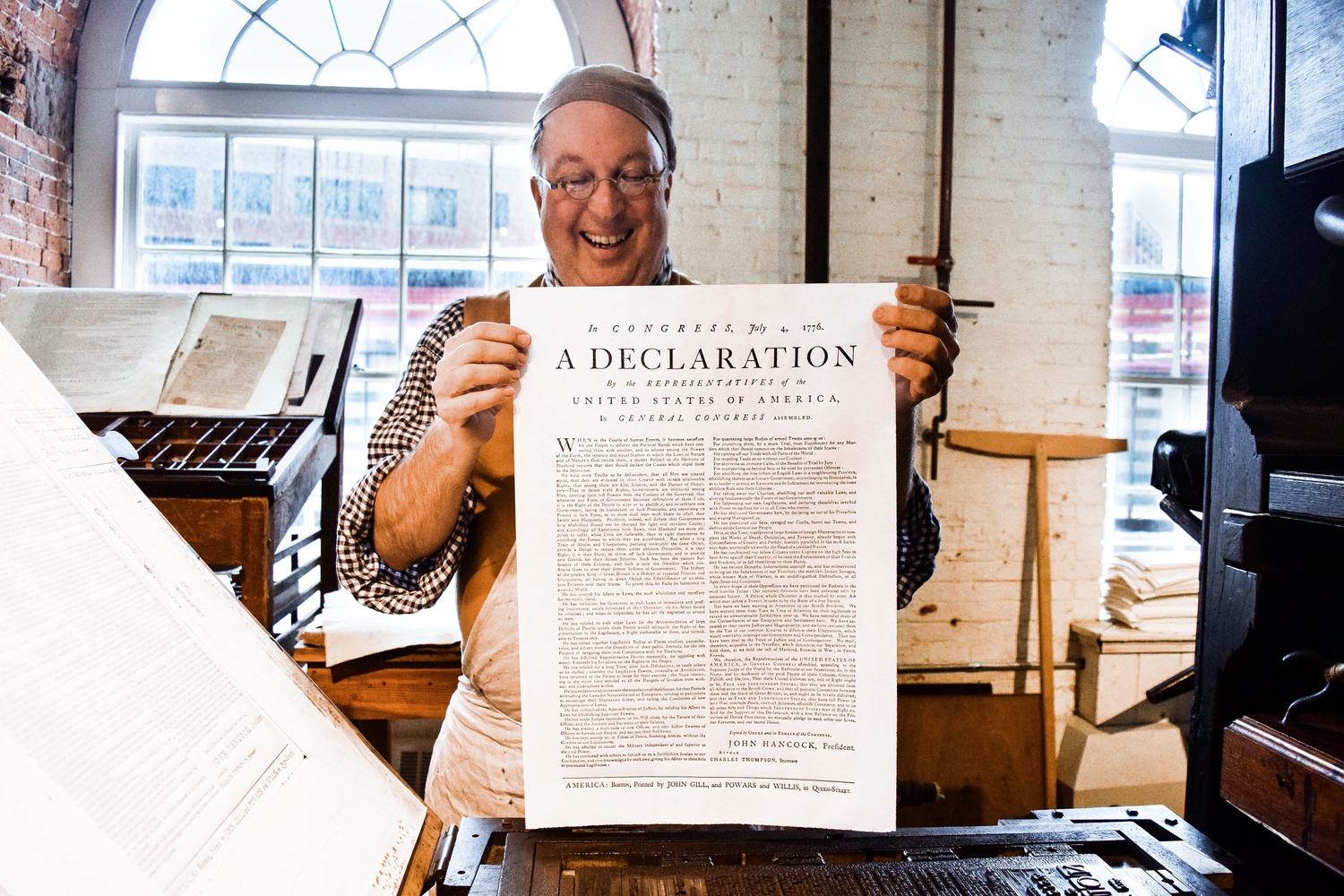

Stepping behind a towering English common press, Gregory grabs an inkball in each hand — leather stretched over sheep’s wool — and blots an array of metal type with a rapid up-and-down motion. He grunts as he pulls a long, wooden handle toward himself with a blazing grin, pushing the inked panels onto linen paper. “That’s why they call it a printing press,” he tells about two dozen tourists. The final product is the Declaration of Independence, on sale for $17.76.

But before running the Printing Offices of Edes & Gill, Gregory worked as a sales manager for a Fortune 500 corporation in Los Angeles.

“It was actually really fun.” He enjoyed travelling the globe, having access to the “best golf courses and all the best hotels,” and entertaining customers. “But about the time I hit about 27, 28 years old, I had the idea that I wanted to do more.” Unsure of what “more” consisted of, he began with the question, “Who am I?”

The beginnings of an answer arrived in 2000, when he was relocated from sleek Los Angeles to Boston’s historic streets. At a war reenactment at Minuteman Park in Concord, he rediscovered a childhood love of history.

“It was like I was being spoken to by the universe,” he chuckles. “It was a loud voice.” With his wife’s encouragement, he began reenacting. “Boy, does she regret that.” What was then only a hobby quickly evolved from colonial battle reenactment to a deep dive into the American Revolution’s intellectual history, going well beyond “the popular history books.”

“Then 2001 happened. It wasn’t a very good year for the planet.” As business took a hit, he seized the opportunity to, at age 42, leave the corporate world. “At this point it was just management at a Fortune 500 corporation. It wasn’t that fun.”

Again following his wife’s suggestion, he channeled his love of history into a walking tour company. Applying his corporate background, he “started doing heavy research” on the Freedom Trail tourism industry. “What I saw was not particularly good. A lot of good stories, and a lot of bad clothes.” Nobody was teaching the history to the level he desired.

“So I showed up on Boston Common in a $2000 handmade colonial suit. In the 18th century, you don’t go out of the shop in your shirtsleeves, it’s considered your underwear.” The suit was made by the master tailor Henry Cooke, who sews clothes for Mount Vernon and the Smithsonian. Lessons on Liberty, Gregory’s walking tour company, kicked off with a historically-accurate bang. “We started doing real, real history.”

Next on his business plan was establishing a brick-and-mortar store along the Freedom Trail. Through his research, he settled on a print shop.

“Every time you turn around it comes back to that machine.” He gestures toward his enormous press. “I’m like, ‘That’s it! Gotta be printing.’ It is the revolution.” And it was strategic. “There was nothing else like it in Boston, so I felt from a business standpoint that would be good.”

The colonial printing business presented a few barriers: namely, not owning a printing press or knowing how to operate one. Gregory found blueprints from the Smithsonian and planned to build his own printing press before eventually acquiring one from Colonial Williamsburg.

While honing his printing skills (so difficult it would have required a seven year apprenticeship in the 18th century), Gregory searched for a venue.

“I had a lot of people telling me I was nuts.” He recalls asking a prominent Boston architect if there was a space in Boston where he could set up his non-profit shop rent-free. According to Gregory, “This guy leaned back and looked at me and said, ‘You’re out of your mind.’”

Gregory was not discouraged. “When you start down a path of intention, it doesn’t matter when somebody says something like that.” And in 2010, he found the empty Clough House near Old North Church. He told the church, “What I’d like to do is turn this from a liability into an asset for you.” The deal complete, he opened in early 2011, paying no rent.

On a sunny day, while leaning against the side of the Clough House, the architect who “told me I was nuts” walked by. “I said,” — Gregory cocks his head — “Hey. Free.”

Boston itself seems to love the print shop. NBC filmed a clip of Gregory for last year’s Super Bowl for an advertisement promoting Boston’s local color. “I told all my friends I was going to be on television, and they didn’t air it. So you kind of look dumb.”

But months later, Patriots fans, tuning in to 2018’s first game and expecting to see Tom Brady or a Budweiser commercial, were instead met with a man dressed in 18th century attire and operating a colonial printing press.

With his sales acumen and a recommendation letter from history professor Jill Lepore (his second customer), he successfully pitched his business to the city of Boston and upgraded to Faneuil Hall early this year.

Gregory’s enthusiasm spills into his home. Without a television, he says, “I spend all my time doing printing research, revolutionary research.” This summer, he drove 21 hours to Deer Isle, Maine to pick up a 1,800 pound press for the print shop he is setting up in his garage (he also has a 2,000 pound hydraulic paper cutter). The messages he lives by, and that he hopes his shop can spread, are clear: learn about history, and “We need to do what we love.”

He remembers helping a blind customer do both. “She had been studying book arts in college, and she’s read about these presses through her whole academic career, and had no idea what they quote-on-quote looked like.” He brought her to the press and let her feel and interact with it. It was his first time letting a customer make a print. “I’ll never forget it, that first experience.”

Now, he loves giving the most inquisitive third graders, who have proven they “know more than the average bear,” a closer look at the press. “They walk away and the parents say, ‘That made our trip to Boston.’” He has not stopped beaming for minutes.

“I never get tired of it. Ever.”