‘It’s Gifts and It’s Debt'

Between an underperforming endowment, dwindling reserves, cumbersome architectural regulations, and lukewarm support from donors, House renewal is an uphill battle.

It was the spring of 2008, and Faculty of Arts and Sciences Dean Michael D. Smith’s task was cut out for him: renovate several of Harvard’s nearly 100-year-old Houses. The homes of thousands of undergraduates at Harvard, many of the Houses were built in the 1930s and had not been significantly improved since.

By 2008, though, Smith and other Harvard administrators felt it was time to give Harvard’s signature housing system a face lift. The project, called House renewal, was set to renovate each of the 12 Houses and “reimagine” the undergraduate experience.

But that process has proved easier to imagine than to execute. Between an underperforming endowment, dwindling financial reserves, cumbersome architectural regulations, and lukewarm support from donors, the project—now in its ninth year—is shifting gears as construction on Lowell House is set to begin this summer.

Facing these barriers, the University has started to take new steps to finance the project, including incurring debt earlier than initially planned. In the final stretch of its capital campaign, which has raised more than $7 billion, the University has made the House renewal a fundraising priority as it lags behind its other goals. These issues have forced administrators to recalibrate their strategy.

“Shifting from a set annual construction schedule to one tied to the successful achievement of House-level philanthropic goals is recommended,” a 2015 report on the House renewal project read.

Overall, the project has posed a challenge to FAS administrators who must complete it.

“We’re into the projects now that are quite expensive and we’re not getting $100 million dollar gifts,” Smith said.

Uneven Ground

Smith tasked a planning committee with examining all aspects of House life in 2008 to prepare for House renewal, and what he found was troubling.

“There was, ten years ago, a lot more variability in the funds available to individual faculty deans to run the programs within their Houses, which created differences between the Houses that were not really honestly defendable,” Smith said.

Inequities between the Houses were significant. Certain Houses, especially the older residences on the banks of the Charles, generally have larger House Committee budgets, partially due to individual House endowments made possible by past donations.

“Just because historically one House got a big donation at one point and another one didn’t, House life shouldn’t be different between one House and the next House,” Smith said. “We started changing the way the College would distribute money across the Houses and took into account the fact that some Houses might have programming and others won’t.”

Aside from differences in funding, the administration was also acutely aware of an uneven landscape of accessibility across campus. The Accessible Education Office lists wheelchair-accessible social spaces in the Houses online, and River West Houses—Kirkland, Eliot, and pre-renovation Winthrop—had no spaces listed.

The fiscal disparity in House programming, along with necessary accessibility upgrades, were part of the impetus for House renewal in its early days, according to Smith. A steering committee was created to begin drafting plans for renovations following Smith’s investigative task force.

But then the financial crisis hit Harvard, and the size of the endowment plunged by almost $10 billion in a single year. As hot breakfast in the Houses was cut and construction in Allston stalled because of a lack of funds, Harvard remained committed to the House renewal project.

So far, the progress has been relatively steady. Following the smaller renovations of Quincy’s Stone Hall in 2013 and Leverett’s McKinlock Hall in 2014, more extensive projects began.

The full renovation of Dunster House was completed in time for students to re-enter in the fall of 2015 and a fully renovated Winthrop House is on schedule to open in the fall of 2017. Lowell House will begin in the summer of 2017 and is slated to be completed in the fall of 2019.

But the current plans for future renovations stop with Lowell, the most complicated renovation yet. Despite surveying both Kirkland House and Eliot House for possible renovation in 2014, administrators have been reluctant to reveal the next Houses scheduled for a makeover.

“We haven’t ever announced here’s the entire sequence of it because it depended on the financing and everything else from when the House is actually ready,” Smith said. “We don’t actually have an announcement at this time about what House will follow Lowell.”

'It's Gifts and It's Debt'

While FAS is working to raise $400 million for House renewal during its capital campaign, the magnitude and difficulty of funding the project remains much larger, with a price tag in excess of $1 billion.

Following the 2015 completion of Dunster House, Harvard’s most ambitious House renewal project yet, administrators commissioned a report on the progress of the project thus far. Released in May of 2016, the report provided the closest look at the financing of the project yet.

The picture was not entirely rosy. Under financial pressure, Harvard had started decapping—or liquidating—funds in the endowment for the project, a relatively expensive measure.

“Decapitalizations taken to date will remove approximately $25 million of available cash from the FAS operating budget by the conclusion of the Program,” according to the report.

Without cash—FAS has no more cash reserves—and grappling with a struggling endowment, Smith said he is left with only two funding sources to finance Lowell: donations and debt.

“I don’t have any reserves anymore and we’re not decapping anything from the endowment in the FAS to fund this part of this,” Smith said. “So it’s gifts and it’s debt that will fund Lowell.”

Smith declined to provide the exact percentage of Lowell that will be funded by debt, though he deemed the total “quite a bit”.

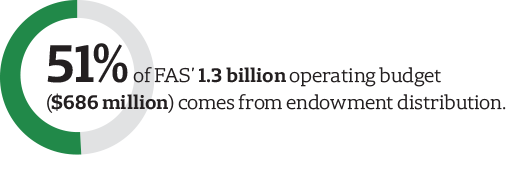

More recently, the endowment’s poor performance—Harvard Management Company returned negative 2 percent in fiscal year 2016—has further limited funds available to FAS administrators. About half of the FAS operating budget comes from endowment distributions determined by the Corporation.

“It only comes to us in prescribed amounts,” FAS dean for administration and finance Leslie Kirwan said, referring to endowment dollars. “And then, because it’s fully programmed into our budget, there’s not extra money.”

'How Do You Do It?'

On top of the difficulties Harvard finding funds for the project, several factors have complicated and raised costs beyond a more typical renovation project.

According to the report, skyrocketing costs of construction drive up the price tag of renovations by 5 to 7 percent a year, not an insignificant amount for a project costing hundreds of millions of dollars.

“Rising construction costs in the Boston market are an issue we identified early on and have continued to monitor closely,” Merle Bicknell, assistant dean for FAS physical resources, wrote in an email. “We’ve had to account for these increased costs in our financial planning and fundraising, which has been very difficult.”

Furthermore, the status of many Houses on the National Register of Historic Places includes cost-increasing stipulations for construction projects, including the preservation of the exterior.

“Just to be concrete about this, I’m not allowed to change the outside of the Houses. They’re historic, especially the Neo-Georgians,” Smith said.

Eliot, Kirkland, Winthrop, Lowell, Quincy’s Stone Hall, Dunster, and Leverett’s McKinlock Hall are all historically protected. Preserving historical standards while conducting major modernization projects is anything but simple.

“If you want to punch a hole through the roof of a historic building, how do you do it?” Smith said.

Harvard must also make the Houses, which were built well before more modern building codes were in place, accessible. The Massachusetts Architectural Access Board requires that five percent of suites, bedrooms, and bathrooms—which cannot be isolated in one area of a building and must be spread around a House—comply with accessibility laws.

“Lowell’s first floor, the number of elevation changes just on the first floor I think is like fourteen,” Smith said. “So you can imagine just how difficult it is to think through these. Our current spaces are not accessible in the ways we like to see it today.”

'Are We Going to Change the Name of Winthrop?'

Even as philanthropy has become one of the primary methods of funding House renewal beyond incurring debt, Harvard has yet to reach its fundraising goal for that category.

Donors say that House renewal is not as exciting as some other priorities.

In an interview in April of last year, Gerald R. Jordan ’61—who has donated tens of millions of dollars to the University—said donors are not enthused by renewal since Harvard is unlikely to rename Houses for donors.

“Are we going to change the name of Winthrop House? I suspect it could probably become the Winthrop-Jordan House or something, but I suspect it won’t happen,” Jordan said.

Peter L. Malkin ’55, for whom the Malkin Athletic Center is named, said that donors tend to want to donate towards House renewal projects as they happen.

“As the work began in Dunster, money began to come in for Dunster,” Malkin said.“It is not realistic to expect that someone would give money for part of the cost of his or her House when that work would not start for six or seven years, or maybe more.”

Smith has recently been doling out recognition for donors in Houses not immediately affected by the current projects as a way to interest a wider set of alumni in the project.

“We differently did the recognition,” Smith said. “You can be an alum of a House and you really want the recognition too be in a particular House and we’ll give you that recognition even though I might have used the donation for a completely different House.”

Typically, major donations have aligned with a House’s renovation. The University announced a new hall in Winthrop would be named after donor Robert M. Beren ’47 in January of 2016, as the project was set to commence months later, for example.

The University also announced earlier this month that a wing of Lowell would be renamed Otto Hall after a major gift by German billionaire Alexander Otto ’90. Construction on Lowell will begin this summer.

“I’m very optimistic ultimately it will reach its goal,” Otto said of the project in an interview with The Crimson. Otto said his memories of House life prompted to donate to House Renewal.

“I think you have to have been there to really appreciate how important life in the House is,” Otto said. “And of course I can understand that others really concentrate more on supporting a specialty in certain academic areas, or research, or professorships, but for me the housing was really particularly important.”

Although Otto’s name will be on a Lowell building, the undisclosed sum of his donation will support the entire renewal project.

Paul A. Buttenwieser ’60, who has donated to the past few capital campaigns, said administrators will approach donors based on their particular interests.

“Their major job is to run Harvard, but in their fundraising capacity, their job is to get to know people. And to bring them in on the work that’s being done,” Buttenwieser said. “It’s not like you go and fill out a questionnaire, ‘What are your interests?’”

Despite the challenges, Smith said he’s optimistic about the future of the project.

“We’re not going to give up, though, on fundraising for House renewal moving forward,” Smith said. “The good thing is, this will not be a surprise to them among that base.”

Buttenwieser certainly is not surprised.

“Harvard wrote the book on fundraising,” he said with a laugh. “They know how it’s done.”

—Staff writer Joshua J. Florence can be reached at joshua.florence@thecrimson.com. Follow him on Twitter @JoshuaFlorence1.

—Staff writer Leah S. Yared can be reached at leah.yared@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @Leah_Yared.