Painting In Color

Stephen E. Coit ’71, a 69-year-old venture capitalist and entrepreneur, is working to improve the representation of people of color at Harvard—one brush stroke at at time.

UPDATED: December 19, 2017 at 9:25 p.m.

Stephen E. Coit ’71 won’t tell you which of the over two dozen portraits he’s painted for Harvard is his favorite.

“I would never answer that because my paintings are like my children,” he said.

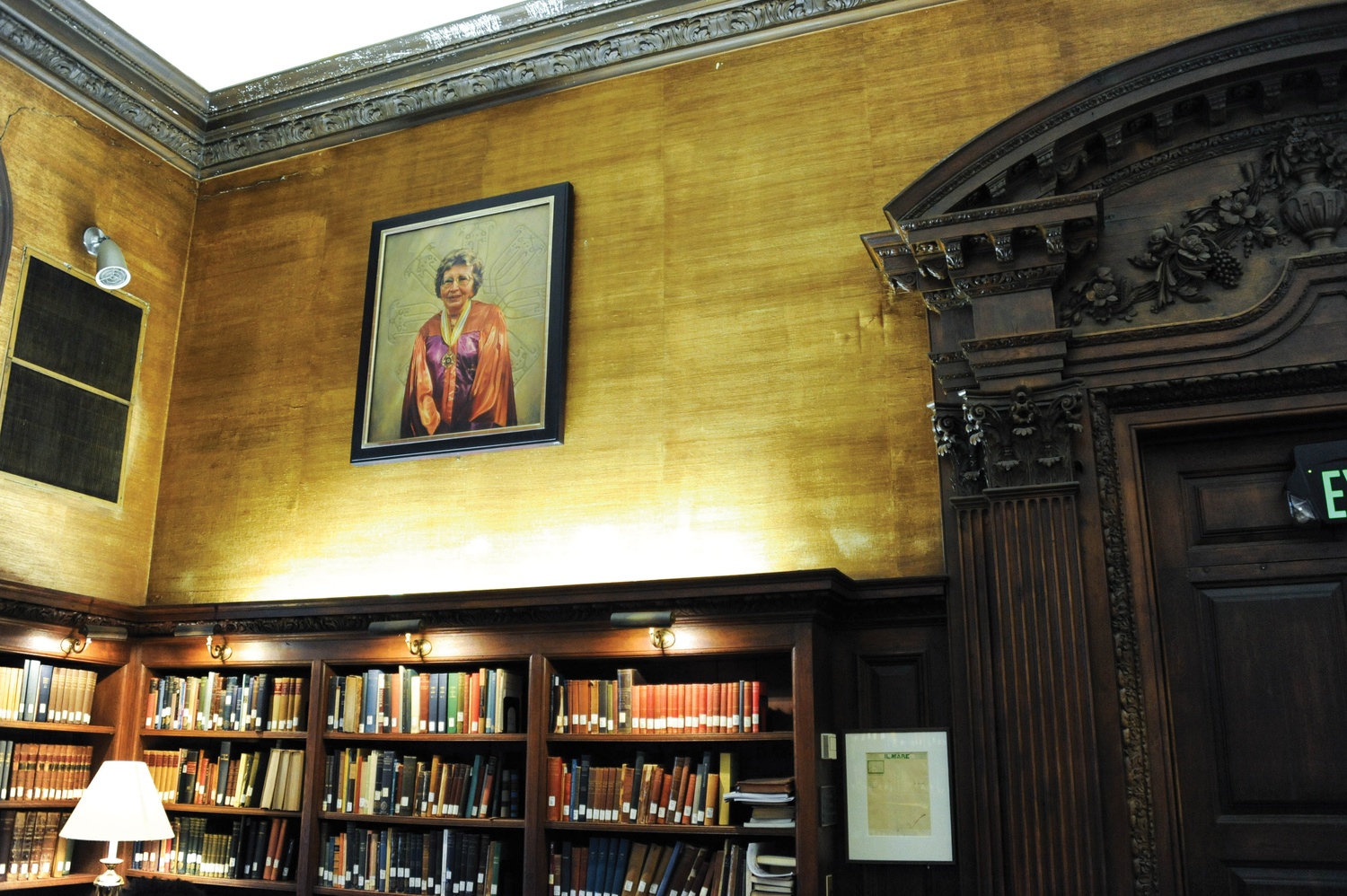

Coit, a 69-year-old venture capitalist and entrepreneur, serves as the official Harvard Foundation Portraiture Artist. In 2003, the Foundation’s Portraiture Committee commissioned him to paint portraits of prominent University affiliates of African American, Asian American, Latino American, and Native American descent who have served Harvard in some capacity for at least 25 years.

But Coit also paints portraits for other Harvard groups including the Radcliffe Institute of Advanced Study. To date, he has daubed 27 pictures of a wide range of individuals spanning University administrators, famous alumni, and prominent government staffers.

Coit has painted figures like University President Drew G. Faust, former Treasurer of the United States Rosa G. Rios ’87, and longtime College admissions officer David L. Evans.

Coit and Foundation officials say his paintings have caused Harvard’s expansive portrait collection—comprising more than 750 oil portraits, according to a 2002 inventory—to more accurately reflect the school’s diversity. But Coit said his portraits may be under threat as Harvard’s 12 residential Houses—where many of his pictures hang—undergo renovations. Further complicating the pictures’ future, the Foundation is navigating a transitional period after former director S. Allen Counter died in July 2017, leaving the organization leaderless.

Coit said he takes the danger posed to his portraits personally—he treats his paintings like people and thinks of them as friends.

“I try to make sure they have good homes and I visit them. I visit them because I live with these paintings in my studio for months,” Coit said. “I remember when [the painting of Sociology Professor] Orlando Patterson left my studio, I missed him.”

'I Can't Be This'

Coit said he often researches the subject of a painting for months before setting brush to canvas. An intense focus on a subject’s personal life and character is an important part of the process, Coit said. For example, his portrait of Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck, the first Native American to graduate from the College, took nine months of research.

Coit’s painting of Cheeshahteaumuck hangs in Annenberg Hall, the freshman dining hall.

Sandra Naddaff, the chair of the Foundation’s portraiture project, called the amount of time Coit spends researching his subjects “quite wonderful.”

“That understanding of the people he is painting and what they contributed to the College are...things that he comes to understand on a very deep level and then is able to embed in the portrait itself,” Naddaff said.

Coit said he believes intense engagement with a subject is necessary for his compositions.

“Having the ability to have a conversation with a painting, to me, is part of my artistic mission,” Coit said.

He said he hopes students who encounter his work will take part in this conversation. Coit’s paintings are currently displayed in several locations on campus including various Houses, dining halls, administrative and academic buildings, and libraries.

Coit said he first seriously tried painting—not counting the watercolors he produced in high school—when he decided to take a sabbatical from venture capital in 1992. Soon after, he “caught a bug” and decided to leave his position to begin painting full time, he said.

He started taking night art classes and traveling to Italy to attend graduate oil painting courses. Coit said he sought to perfect his technique by drawing at every possible moment.

“When I thought I could see my way financially—not some grand one percent piece of the pie, but enough to be a responsible husband and parent—I approached my venture capital fund and said, ‘I can’t be this,’” Coit said.

He officially stepped away from venture capital in 1996, and said he has never looked back. Today, in addition to takings commissions, he occasionally teaches painting courses at Lowell House. Carol A. “Kitty” Pechet, an artist who participated in one of Coit’s classes, said she admires Coit’s process and the details he includes in his work.

“He seems to be able to put the character of somebody into vision. That’s not so easy,” Pechet said. “He has a dimensional understanding of them. That’s why the paintings aren’t empty or flat.”

'On Our Walls'

When Coit, who is white, was being interviewed for the position of official portraitist for the Foundation, he said Foundation committee members like Reverend Peter J. Gomes quizzed him about his ability to represent people of color faithfully.

“I said that there are no two people that have the same color skin and that achieving the proper color of skin to me is easier than painting the color of pink granite in Maine in the morning fog,” Coit said.

Coit said he believes every person, situation, and lighting setup is different. He added “acute observation” is critical, especially when seeking to represent people from diverse racial backgrounds. Harvard students and officials say diversity at the College is increasing—and claim Coit’s portraits are more critical now than ever.

Lowell House Faculty Dean Diana L. Eck, who said she has worked at Harvard since the 1970s, said she thinks the College has made great progress on increasing diversity. According to The Crimson’s survey of the incoming class of 2021, the class is majority female and boasts a significant increase in the number of students of color from previous years.

“Now we have all of this diversity and it’s an enriching thing for Harvard College,” Eck said. “It’s important for our education, for our intellectual life and for our life with one another. Not to have that displayed in some meaningful way on our walls is a mistake.”

Coit painted Rios, former treasurer of the United States and the first Latina to have a portrait at Harvard, in 2015. Her portrait now hangs in the Junior Common Room at Winthrop House.

In an interview Thursday, Rios said Coit’s portraits are inspirational to undergraduates.

“I’m a big believer in this next generation of leadership having inspirations in order to have aspirations,” Rios said. “These types of opportunities to showcase and highlight examples of people who kind of walked through the fire, if you will, and took those strategic risks are important.”

Devontae A. Freeland ’19, an intern at the Harvard Foundation, said he sees similar value in displaying portraits of diverse figures at Harvard. He said he thinks what a prospective student likely saw on Harvard’s walls 20 years ago differs widely from what students see today.

“I think that those symbols actually make a difference and that can make a real impact on Harvard’s recruitment, on our bringing in the best and brightest talent and not having people be discouraged because they feel Harvard doesn’t value or represent their particular race or identity or gender,” Freeland said.

‘A Bit of Immortality’

After the passing of former Foundation director Counter this summer, some say the organization’s portraiture project faces an uncertain future—particularly as Harvard seeks to overhaul and renew each of its 12 undergraduate Houses.

Coit said he is worried House renovations could mean his portraits will be moved to less visible locations, something he considers contrary to the mission of the project as a whole. Lowell House, home to at least two of his portraits, will remain under construction until the fall of 2019—and Adams House, which boasts at least one of his pictures, will begin undergoing renovations in June 2019.

Apart from concerns over portrait relocation, Coit said he thinks the newly remodeled Houses may not provide the appropriate aesthetic backdrop for his paintings.

“Just because it looks modern and sleek and it’s made of glass and you can see through it and it’s got a metal frame and the light is cool, doesn’t mean it’s teaching you anything about who went before you and what your job is here,” Coit said.

Naddaff, the chair of the portraiture project, acknowledged the importance of displaying the portraits in locations where they are visible to undergraduates. But she said other locations may be more valuable than the Houses. In particular, she mentioned hanging portraits in Annenberg, Lamont Library, and University Hall.

“I think, for most us, the Houses are where we think the students are, but certainly students are in many different buildings,” Naddaff said.

The project’s future may also be in doubt due to Counter’s passing, according to Florence C. Ladd, novelist and former director of Radcliffe’s now-dissolved Mary Ingraham Bunting Institute.

“Dr. Alan Counter was instrumental in heading the project. Now that he has passed away, I don’t know where the initiative to continue the work rests,” Ladd said.

Asked whether the group would continue its work despite Counter’s death, Naddaff said she believed it would.

“I have no reason to believe that it will not be sustained as a commitment,” she said.

Regardless of the portraiture project’s fate, Coit said he thinks the portraits he has already painted leave a legacy that will last for decades.

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

CORRECTION: December 19, 2017

A previous version of this article incorrectly indicated that Rosa G. Rios ’87 is the first Latina treasurer of the United States. In fact, she is a former treasurer of the United States and the first Latina to have a portrait at Harvard.