News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

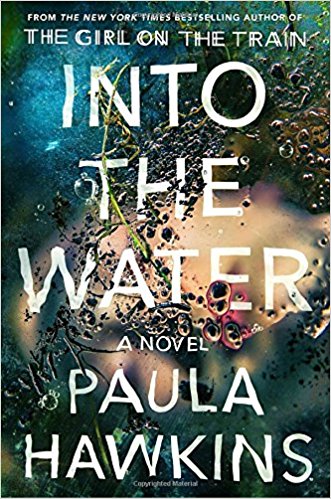

'Into the Water' Is A Diluted Thriller

2.5 Stars

“Into the Water,” Paula Hawkins’ newest thriller, takes a different path from her previous bestseller, “The Girl on the Train.” While her first thriller is a more straight-forward “who-dunnit” mystery, “Into the Water” implies that some of its supposed murders may actually have been suicides. Hawkins plays with the novel’s title by using water terminology to describe many scenes. Furthermore, the novel’s lack of likeable characters make it difficult to connect to any of them, and the problematic portrayal of suicide heavily detracts from the gripping plot.

The main mystery of the novel revolves around the inexplicable deaths of a local mother and a (seemingly) unrelated teenage girl at the legendary Drowning Pool, an area of the river where various women have died there within the same year. Police wonder if they were suicides or murders made to look like such.

While the police investigate, others in the town—especially those who were close to the victims—act in a way that creates a problematic depiction of suicide. Instead of discussing suicide as a product of mental illness, suicide is seen as an action with specific people to blame for it. Depression is ruled out almost immediately as a cause when loved ones claim the dead weren’t depressed, despite the fact that depression can often be invisible to others. The book misses an opportunity to address an important health issue.

Hawkins unfortunately relies too heavily on the unoriginal—albeit potentially interesting—use of water as imagery. At first, the imagery feels fitting considering the victims were found in a river, but it becomes cliché with overuse, like when Hawkins writes that Although initially quaint, this technique quickly gets old. Even Hawkins herself seems fed up with her own writing: “There was the water: that was it,” she writes. Aside from water imagery, general terms like “She felt bad” and “Good days and bad” reveal lazier stylistic moments, and Hawkins also relies too heavily on frank, short sentences.

However, the novel’s fatal flaw has to be the characters’ unlikeability. While the fast plot can certainly keep readers entertained, the characters are too frustrating to empathize with. They refuse to communicate despite knowing that a simple conversation would solve the entire mystery and settle conflicts between the living. This unreasonable situation is a cheap plot that might add to the mystery’s intrigue, but it significantly decreases the fun in learning each character’s backstory.

Hawkins attempts to keep her novel interesting by alternating between points of view. But because there is a sheer multitude of narrators, she ends up spreading the story too thin. With over one hundred pages left in the novel, Hawkins seems to come to a conclusion about the suspect’s identity. However, this quickly changes as the novel progresses. Because there are so many characters, all of whom are unlikeable and possible culprits. Hawkins is able to switch the blame multiple times. In theory, this sounds like an opportunity for many dramatic twists. But the novel feels more like Hawkins finished writing the book before deciding she needed to add one hundred more pages. For any thriller, the ending is crucial to the story’s success, and with its unsatisfying conclusion, “Into the Water sinks instead of swimming.

A quick read, “Into the Water” definitely has its flaws. Overplayed references to the river lies lazy writing and while the possibility of suicide adds an extra wrinkle to the mystery, Hawkins fails to address this mental health concern appropriately. The curse of the sophomore slump holds true for Hawkins, as “Into the Water” falls short as a disappointing follow-up to “Girl on the Train.”

—Staff writer Caroline E. Tew can be reached at caroline.tew@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.