News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

‘Younger Now’ an Unconvincing Return to Roots

2.5/5 STARS

From Lorde’s “Melodrama” to Taylor Swift’s “Reputation,” 2017 is shaping up to be quite the year of pop reinvention. Miley Cyrus, reeling from the excess of her “Dead Petz” era, is no exception to the trend. Her new album “Younger Now,” released on Sept. 29, is both foreign and familiar. In a sharp departure from her most recent work, Cyrus attempts to return to her country-pop roots in an act of artistic rebirth. Unfortunately, though “Younger Now” begins pleasantly enough, it lacks the thematic continuity necessary to establish the persona shift she seeks.

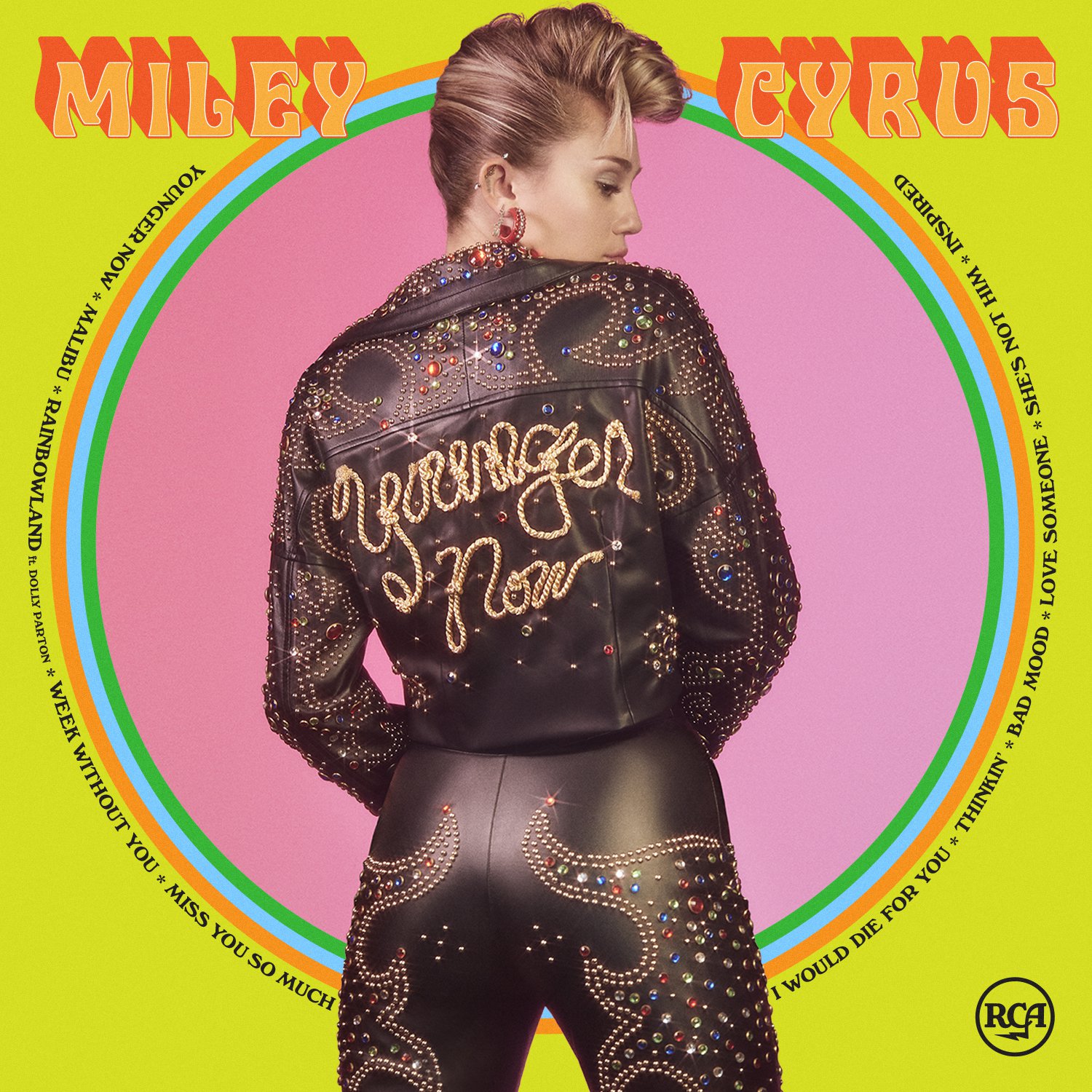

At first look, the album presents itself effectively. The title is evocative of a deep contradiction in this new Miley: To progress, she must embrace the regressive. Her cover art mirrors these sentiments. Plastered with bright, bubblegum colors framing Miley in leather greaser getup, the image is invitingly retro. It’s a thinly veiled rejection of her last two album cycles, and a marked pivot toward accessibility by the general public. Decked out in familiar apparel and referencing an older, more accepted Miley, the album presents the performer as someone we know—and perhaps even wish to get to know again.

“Younger Now” opens with its namesake, a strong start to the collection. The introduction, around 15 seconds of pure rain sounds, is an appropriately restorative break from her past work. The opening line, “Feels like I just woke up / Like all this time I’ve been asleep,” outlines this sentiment as well. Coupled with an electric guitar riff, the words are simple but honest. As a whole, the song signals an album which is introspective and reactive: Cyrus confesses in the chorus, “I’m not afraid of who I used to be.” Though the song is not groundbreakingly experimental, the pendulum has certainly swung back from the provocateur-Miley of the early 2010s.

“Malibu” is a clear musical successor to the first track, relying on an uptempo, drum-and-guitar-backed melody carried by the musician’s beautiful vocal timbre. Cyrus’s voice shines through in this album, both dreamlike and clear. “Rainbowland,” the only song featuring a different artist—Dolly Parton, her godmother, no less—is charming. Sampling a conversation with Parton, the duet’s harmonies give the track volume, and the quiet encouragement to “brush the judgment and fear aside” feels vaguely political without being divisive. The first quarter of the album is mellow, somewhat monotonously saccharine in a way that is uncharacteristic of Cyrus.

Though aptly launched by its opening tracks, the album never truly takes off past its starting point. The next stretch of the album is thematically dissonant, abandoning the cheeriness of the first three songs to instead confront the idea of loss. “Week Without You,” a breakup song which serves as a foil to the love expressed in “Malibu,” is grittier. Drawing on rock influences, the track is percussive, carefree, and dripping with attitude. “Miss You So Much,” a breathier and more emotionally distant piece, targets a different type of loss. Asking rhetorical questions such as “How can I miss you so much when you’re right here?”, the fifth track reverentially approaches the idea of memory. “I Would Die For You,” a shorter song with no intro or outro, marks the center of the album and associates great love with sacrifice. Strong as though the tracks may be in a vacuum, they represent an abrupt and frankly confusing turn from the dreamy positivity of the first tracks.

The second half of the album further diffuses its thematic energy. “Thinkin’” and “Love Someone” continue the breakup theme in an aggressive and strangely accusatory way. The former, though easy to listen to, is punctuated by repetitive single-note melodies coupled with a lack of lyrical depth. The latter, showcasing lyrics like “to make somebody stay you gotta love someone,” is vocally impressive with its belting, but the catharsis of the track feels unearned.

The album, far derailed from its earlier optimism, is unsuccessfully wrapped up by the closing track “Inspired.” The song, saturated in nostalgia, features country strings and heavy references to family. Urging the listener to “pull the handle on the door that opens up to change,” the closer echoes the transformation driven in by the rest of the album. And yet, for a conclusion to the album, the piece goes on convoluted tangents, including a warning about dying bees and overtly political undertones absent from the majority of “Younger Now.” The final lines of the album, a radical departure from the beginning, are nihilistic: “But how can we escape all the fear and all the hate? Is anyone watching us down here?” Though the songs set out to contemplate such questions, they raise a different one for the listener—how exactly did the album end up here?

“Younger Now” is not bereft of enjoyable moments—its title track and “Rainbowland” are clear evidence of Cyrus’s pop sensibilities. The the album is ultimately unsuccessful, however, in rehabilitating Cyrus’s country-pop image. The bait-and-switch of frontloading the album with her brightest tracks causes a slump in the second half. And the blatant rebrand beneath the guise of artistic reinvention—not even reinvention so much as return to an earlier style—feels forced rather than inspired. Though Cyrus manages to write several pleasing tracks, her “Younger Now” is mired in its purpose: To move forward, she tries to go back, and accomplishes neither.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.