News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

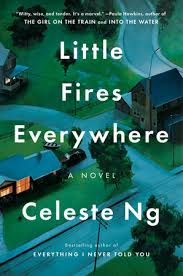

A Quiet Town Set Ablaze in ‘Little Fires Everywhere’

4 Stars

“Little Fires Everywhere” is a slow burn of a novel. Celeste Ng—author of the New York Times bestseller “Everything I Never Told You”—begins her second book with the literal combustion of the brewing racial and familial tensions in a sleepy Ohio town: “Everyone in Shaker Heights was talking about it that summer: how Isabelle, the last of the Richardson children, had finally gone around the bend and burned the house down.” From there, the novel dives into the past, tracing how a picturesque family, a nomadic artist, and a Chinese-American baby with an ever-changing name can start a fire.

Shaker Heights claims to be a model community of early 90s progressivism. At the town’s heart are the Richardsons, a white, picture-perfect family. The mother, Elena Richardson, is a small-town journalist with dreams bigger than her bylines. She and her husband have four children: Lexie (the popular high school senior), Trip (the charismatic junior), Moody (the soft-hearted sophomore), and Isabelle (also known as Izzy, the family’s rebellious, artistic misfit).

Enter the Warrens, a family of two. Mia Warren is a photographer who moves whenever she “gets the bug.” Her daughter, Pearl, has never had her own room before. Their arrival to Shaker Heights garners an obsession from their landlord—the Richardsons. Moody falls in love with Pearl, who becomes Lexie’s best friend and Trip’s secret girlfriend. Izzy hires herself as Mia’s unpaid apprentice, and Mrs. Richardson launches her own private investigation into Mia’s mysterious past, abusing her journalistic connections in the process.

This might sound like the grounds for a cheesy TV drama, but it isn’t. Characters that could easily fall into shallow tropes don’t. Ng is smarter than that. She has the deft hand of a science fiction writer, entrenching the novel with world- and character-building detail. Every now and then, she steps back to show her skill in seemingly tangential vignettes, like when she describes Izzy’s affinity for rebellion: “When they went to the pool, Lexie and Trip and Moody were allowed to splash in the shallow end, but Izzy—then age four—had to sit on a towel, coated in sunscreen and shaded by an umbrella. After a week of this, she jumped headfirst into the deep end and had to be rescued by the lifeguard.” But every line is a catalyst for the inevitable fire, thus forming a tight, coherent story within the book’s concentrated universe.

Ng devotes much of the novel’s time to tenderly and precisely fleshing out the motivations of the Richardsons and Warrens. However, because the bulk of “Little Fires Everywhere” revolves around these two families, Ng ends up glossing over the true conflict that ignites their idyllic little town—at least, the conflict that’s marketed as such on the book jacket. About 100 pages in, the Richardsons visit the McCulloughs, who are showing off their brand new one-year-old child—an adopted Chinese-American girl they’ve dubbed Mirabelle Rose McCullough. After several miscarriages, a baby is all Mrs. McCullough could have ever asked for, and it seems like their perfect lives are finally complete. That is, until Bebe Chow, Mirabelle’s—or May Ling’s—biological mother enters the picture, starting a custody battle that splits apart the town.

Theoretically, there could be more time spent on the emotional distress that comes with the question of heritage and ownership, the desperation of unfulfilled motherhood, and the power dynamics between a Chinese immigrant and a wealthy white woman. Ng does take a few chapters to explore these themes, but they are always firmly in the background of the Richardsons and the Warrens’ own discord. It’s unfortunate because it never feels like there are real stakes and crystallized characters in the custody battle, thus reducing a necessary dialogue to a plot device. It’s only disappointing if you were expecting the novel to be a full focus on racial prejudice and class privilege.

But that may not be what “Little Fires Everywhere” is trying to do, despite the marketing angle. Mia Warren’s backstory is still vivid and fascinating. The placid ignorance and “progressiveness” of Shaker Heights belies the town’s aggressive response to anyone who tries to disturb the peace. Mia’s and her daughter’s interactions with the McCulloughs definitely flare up with conflict much later in the novel, but the painstaking care Ng takes to set up the fire is nothing short of brilliant. “Little Fires Everywhere” may not be the book its plot summary suggests, but Shaker Heights and its residents are mapped out with intense sharpness, making this fully-imagined novel still worth the visit.

—Staff writer Grace Z. Li can be reached at grace.li@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @gracezhali.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.