News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

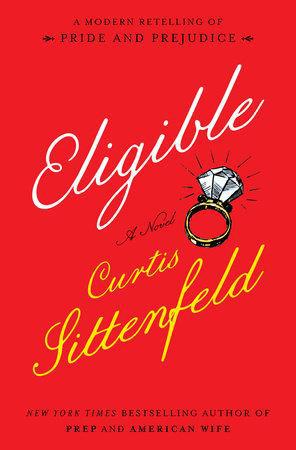

‘Eligible’ a Successful Play on Austen

"Eligible" by Curtis Sittenfeld (Random House)

Curtis Sittenfeld’s recent reworking of Jane Austen’s most famous work, “Eligible,” does not begin with the quintessential line, “It is a truth universally acknowledged,” but the question of marriage—or the lack thereof— does immediately become a topic of interest for its characters. As a modern-day take on “Pride and Prejudice,” Sittenfield’s book keeps close to its inspiration’s main points of conflict; issues of class, vanity, and love run rampant within its pages. But to weigh the thematic value of “Eligible” against that of the classic novel would be to do Sittenfeld’s work a disservice. “Eligible” does not promise to be another “Pride and Prejudice.” While its plot might be similar (albeit with much-needed contemporary twists) and its characters might possess the same names, it does not try to evoke poetic phrases or present mind-shattering commentary on the world. Instead, Sittenfeld has successfully crafted a fun, engaging romp whose greatest mission is to excite any Jane Austen fan.

“Eligible” is both familiar and not: Liz Bennet, a 30-something magazine writer, and her older sister, Jane, have not had the best of luck in love. Liz is currently in an affair-but-not with her crush of over a decade. Jane, approaching 40, is still without a husband or child, having turned to a sperm bank to fix the latter problem. When their father has a heart attack, the two sisters return from New York City to Cincinnati to care for him and find their stately home and not-so-stately family in incredible chaos. But Liz’s attempts to take control of the situation spiral out of control when the family meets Chip Bingley, a doctor and past contestant on the reality TV show “Eligible” (the book’s version of “The Bachelor”), and his brooding neurosurgeon friend, Fitzwilliam Darcy.

The updated plot allows Sittenfeld to surprise the reader by playing off well-known elements within the story of the original and adding new twists. Jane’s use of artificial insemination changes the nature of the initial fallout between Bingley and Jane, while Bingley’s past participation in “Eligible” becomes a crucial part of their eventual reunion. Wickham—the soldier who captures Elizabeth’s fancy and elopes with Lydia in Austen’s original story—becomes two different characters with surprising backstories, incredibly different from the handling of the character in “Pride and Prejudice” but well-updated for the new setting and time period. Such changes let Sittenfeld to honor the original while keeping the reader hooked and chortling at any unexpected development. Furthermore, Sittenfeld shows incredible awareness of her source material and uses the reader’s familiarity with the story to her advantage—often to comic effect. In “Pride and Prejudice,” Darcy insults Elizabeth’s family and then declares his love for her, saying “You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you.” But in “Eligible,” when Darcy shows up at Liz’s door to confess his affection for her early in the morning (“I was in my pajamas and didn’t even have a bra on,” Liz tells Jane in a comment that further highlights the awkwardness of the situation), his proclamation is just as memorably haughty, though now he insinuates that his love for her is “probably an illusion caused by the release of oxytocin during sex.” This interplay between science and romance, situated in a version of a classic novel, not only emphasizes the modernity of Sittenfeld’s tale but also adds a touch of newfound humor to the situation.

Besides revamping the story, the novel reinterprets the classic characters of “Pride and Prejudice” while simultaneously granting them a sleeker, more modern dimension. In particular, Sittenfeld endows the entire Bennet family with a certain vivacity; Mr. Bennet, for instance, is still his unforgettable wry self, but now his humor is more casual and packs a harsher punch. “A reality show isn’t unlike the Nobel Peace Prize, then…. in that they both require nominations,” he notes early on in the novel. The care with which Sittenfeld portrays the Bennet family, perhaps even greater than the care with which she portrays Liz’s romantic interest in Darcy, suggests her greater fascination with family dynamics than with romance—

and while the novel contains enough sexually intense interactions between Darcy and Liz to satisfy any Austen diehard, the duo’s interactions fill a relatively small portion of the novel’s 500 pages. Sittenfeld still considers marriage, but a family’s change becomes much more important. This decision is a successful one: Not only does it differentiate the story from its predecessor, but it also feels more suitable for the world in which the characters now exist. As a modern woman, Liz will not let a suitable marriage define the rest of her life—she already has a stable income from her work—so it is reasonable that her daily worries consist more of tending to her family and balancing her work.

To emphasize the new setting further, contemporary issues receive some attention. Mrs. Bennet is racist and anti-Semitic, and both she and her husband are unaware of what it means to be transgender. The Affordable Care Act receives several mentions throughout the story, especially when the characters discover that the Bennet parents do not have health insurance. Yet while the novel touches upon these weighty political issues, it does not philosophize; in fact, the mentions are brief sentences and phrases in a much longer dialogue or narration. Sittenfeld is not interested in making a social argument—rather, she alludes to these topics to show how the characters are now operating within more modern contexts.

The melding of gravity and flair with a rejection of all intellectual pretense also appears in Sittenfeld’s writing style. Sittenfeld does not string together poignant phrases into paragraphs, instead employing a breezy language that makes the novel quick and easy to absorb. Yet she often engages in witty wordplay: “[Love is] a condition that’s acute, not chronic,” Mr. Bennet says. The effect is an awareness of the thematic and stylistic value of the original novel, but one that does not strive to clone this appeal, instead opting for more comedic means.

Ultimately, “Eligible” is a light-hearted and hilarious read for lovers of Austen’s works or for those in search of a clever romantic comedy. The novel is not the most revolutionary book on the market, but then again, enlightenment does not seem to be Sittenfeld’s goal. Instead, she seeks to pay homage to a famous work of literature by giving it a fresh and entertaining makeover. There exist many truths in this world, but for Sittenfeld in her latest book, the greatest truth is the universality—one transcending centuries and countries—to be found in Austen’s beloved tale.

—Staff writer Ha D.H. Le can be reached at ha.le@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.