All Over the Map

Photographs of Dr. Alexander Hamilton Rice Jr., class of 1898, are pretty much exactly what you’d expect.

A sepia tint of Rice in an unnamed exotic locale portrays the quintessential turn-of-the-century explorer. Squinting eyes hovering over a full white beard and mustache, Rice sports a wide-brimmed hat to shield him from the sun beating down on the makeshift camp. Rice, a wealthy Amazon adventurer, smiles and gazes somewhere out of frame, an imperialist hero straight out of Kipling.

Rice spent much of the first quarter of the 20th century exploring and mapping swaths of the Amazonian basin, a pursuit that would bring him glory, fame, an honorary third degree from Harvard, and the hand of Titanic survivor Eleanor Elkins Widener, who met Rice at Harvard when she bequeathed the library named for her drowned son. In 1929, Rice made a donation of his own, adding Divinity Ave. to his growing list of conquests by founding the Harvard Institute of Geographical Exploration.

Over the next two decades, the Institute launched several expeditions to various unexplored corners of the world and came back with new maps. Courses in cartography, aerosurveying, field communications, and “exploration in general” were offered, reported the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Perhaps most importantly, the Institute amassed a collection of mapping tools to rival any in the world: some 102,000 maps, 20,000 books on exploration, and a variety of cartographical instruments.

In concert with Harvard’s already formidable Geography Department, the independently operated Institute put Harvard near the center of the mapmaking world. But by the late ’40s, things had changed and the department closed.

“So there’s some scandal involved and some politics,” David Weimer says, a specialist at Harvard’s Map Collection. “Depending on who you ask about it, they’ll emphasize different parts.”

There are three theories.

The first is one of divisive interdepartmental politics. At the time, the field of geography was undergoing a schism from which many believed it could not recover: While some geographers were staunch believers in a more traditional, geology- and topography-based approach to study, others, including head of Harvard’s Geography Department Derwent Stainthorpe Whittlesey, practiced “human geography”—a more blurry (and, at times, ethically questionable) discipline that attempted to more or less link racial and ethnic differences to contingencies of geographic location. (In the ’40s, Whittlesey published papers on the “Environmental Foundations of European History” and “German strategy of world conquest,” among others.) As the divide grew, professors became entrenched, and squabbling for resources and academic superiority brought the department to a close.

The second theory comes straight out of a spy novel: “People say it was a part of the Cold War—the CIA wanted to be in charge of mapmaking,” Weimer says, so the government shuttered Harvard’s department.

The third and most widely accepted theory is something uglier. In the mid-20th century, a number of Harvard’s geography professors—including Whittlesey—were gay. The story goes that, to avoid openly firing the professors, Harvard quietly disbanded their department. The closure of Geography as a study at Harvard touched off a wave of similar moves at universities across the country; effectively, for some, it was the death of a field.

To this day, the circumstances around the end of the Geography Department remain shrouded in uncertainty. The excuse given to the Crimson in 1948 seems almost comically unspecific and dismissive.

“Harvard cannot hope to have strong departments in everything,” the University is reported to have said. In any case, Geography was gone for good.

Or so it seemed.

MAP COLLECTION

The closures of the Geographical Institute and Geography Department, of course, did not signal the end of cartography-related pursuits at Harvard (just as it failed to bring an end to interdepartmental squabbling or gay professors).

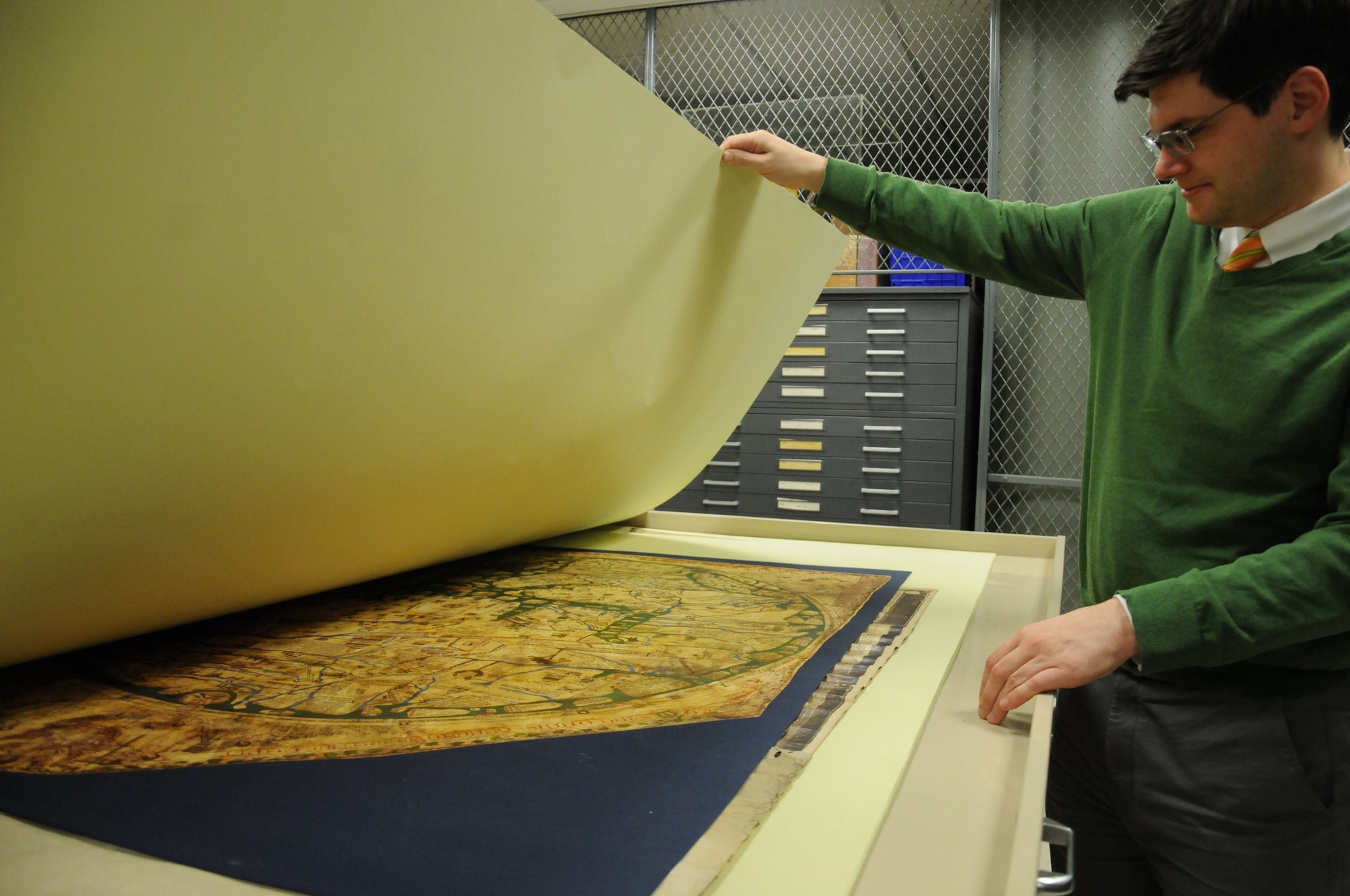

The back rooms of Harvard’s Map Collection in the subterranean levels of Lamont are a trove of all things cartographical. Shallow metal drawers (from standard to “ultrasize”) contain neat piles of maps and charts dating back as far as 1493. Rolled-up wall maps stack all the way to the ceiling, looking for all the world like ancient scrolls containing some obscure magic. One room is full of atlases—some 20,000 of them—ranging in size from a deck of cards to massive poster-sized leather tomes.

The underground archive is not without some whimsy, as well. In the atlas room, there are two boxes full of postcards from around the world and across time that no one has gotten around to reading yet. There is also, delightfully, an “Official Map of the Harvard Map Collection” hanging on one wall, helpfully discrediting the many Imposter Maps of the Harvard Map Collection which doubtless abound.

When Rice’s Geographical Institute was dissolved, its holding of maps and map-related objects were absorbed into the already formidable Harvard library collection and now make their home amongst the Collection’s half million maps and atlases. This collection started in 1818 upon the donation of a wealthy maps merchant, says Weimer.

Weimer is the collection’s newest hire. He works, he tells me, on “vision, visualizations, and space”—in part looking at maps for the blind whose mountains and valleys and borders are physically embossed into the page, creating slightly 3D maps which can be tactilely read.

Among the Collection’s holdings, there are early outlines of the Yard inked in spidery hand, maps of Africa looped over with ornamental arabic, facsimile mappa mundi depicting monstrous human-beasts in unexplored corners, globes Mercator, atlases Ptolemaic.

Today, some of those maps are being taken to new frontiers.

UNCHARTED

Harvard’s Center for Geographic Analysis is surprisingly difficult to find.

Nestled in the basement of CGIS Knafel building, the collection of monitor-lined offices is perhaps a far cry from Rice’s literal brick-and-mortar institution and even from the labyrinthine archives of the Map Collection.

But here, too, there’s cartography at work which that likely astound Rice. Monitors at the Center’s main entrance display brilliantly lit, pulsating digital maps. On one, feathery white lines representing wind sweep across the continental U.S. in real time; on another, world cities emit ominous spears of light at one another while a scrolling stream of data below logs the impacts.

Professor of Anthropology Jason Ur is the faculty director of the CGA, a support network for students and faculty undertaking geographic and spatial research.

“Students and faculty are interested in using these digital tools, but they don’t know how to,” Ur says. “But they have these questions. For us, we’re interested in the questions coming first.”

Ur also co-teaches Anthropology 2020, an archaeology course in which students overlay old inked maps, many from the Collection, with high-tech satellite and computer images to pinpoint potential archaeological sites. The result is a layered image where “peeling” back each layer reveals different strata of history.

In the constellation of pixels that emerges, Ur’s students are able to effectively build maps of not just place but also time. “We’re trying to bring all of this together so that we can have a very rich mapping of the modern landscape, but [also] the past landscape,” Ur says. One of his students is working on locating Aztec settlements today buried beneath the urban bustle of Mexico City, another on Viking-era settlements dotted along the edges of massive Greenland glaciers.

For Weimer and Ur, the shuttering of the Geography department in 1948 still casts a shadow.

“Geography is important,” Ur says. “This is something that you’d never guess from being at Harvard since we don’t have a geography department.”

In Weimer and Ur’s work, there are echoes of a philosophy which would have been familiar to those Harvard geography founders, even if the technologies they use would have been alien. Ultimately, Ur comes down on a side that perhaps both Rice—Panama hat and charting implements in hand—and Whittlesey—tying the peculiarities of topography to the turbulence of history—might have approved of.

“Increasingly, especially as these new digital tools become available, in the social sciences and the humanities, scholars are realizing that geography matters,” Ur says. “It’s not really possible to approach these questions without a good set of tools.”