Norse Code

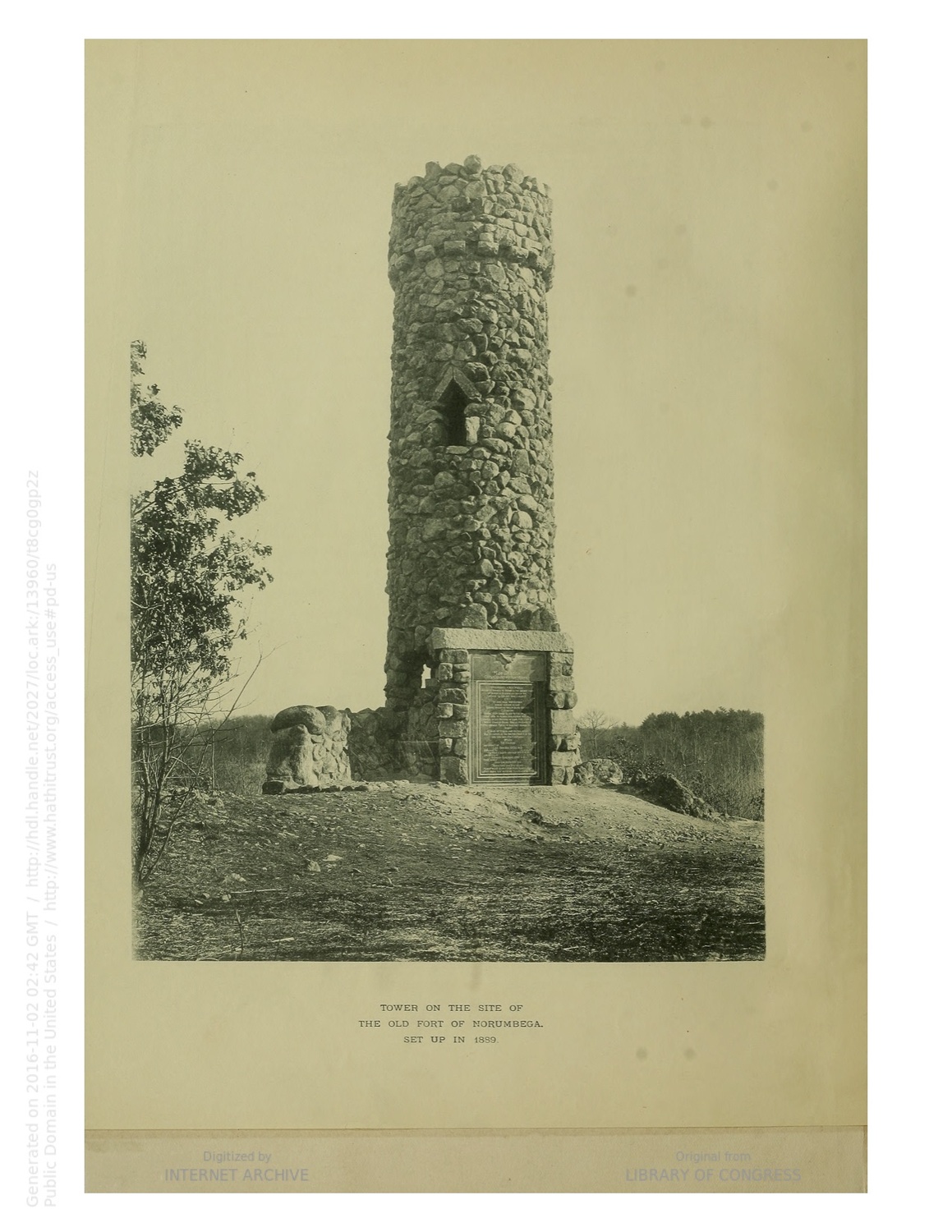

The only even remotely Viking feature at Norumbega Tower in Weston, Mass., is the plaque carved out of what appears to be an entire kitchen counter. You could just about pretend that the teenaged couples’ engravings along the tower’s flanks are traces of skirmishes past, and that the roar of the cars through the trees is the rushing of a mighty river—but the illusion doesn’t last long. You might begin to feel bad for being so distinctly un-transported to any Norwegian township. Thankfully, you don’t have to worry. There never was a Norwegian township here.

It was Harvard professor Eben Norton Horsford who commissioned all 40 feet of the tower to be built and wrote the immense plaque commemorating the Viking fort of Norumbega. Never mind that Norumbega didn’t exist, or, if it did, was 1,500 miles from the corner of Weston that he chose as its site. This didn’t stop him from commissioning a statue of Leif Erikson which stands today in the middle of Commonwealth Ave., from installing a six-foot-wide plaque on Memorial Dr. to mark the spot of Leif Erikson’s house, or from publishing several books on the Viking settlements of New England. This was a man on a mission, so much so that the mission’s complete and utter lack of evidence was the tiniest of setbacks.

Horsford is better known as the co-founder of Rumford Chemical Works. The ubiquitous shiny red containers of baking powder are Horsford’s packaging and his formula. He co-founded Rumford Chemical Works in 1854 after patenting his “double acting” baking powder, a huge hit because—according to Pia Sorensen, the preceptor of the popular class Science and Cooking—baking had hitherto been an expensive and inconvenient process, involving fermented milk or tartaric acid to aid in leavening. Horsford’s stable, portable reformulation was lauded by the American Chemical Society as one of the “seminal achievements in the history of the chemical sciences” in 2006; it made him a fortune.

Not all of Horsford’s worth, though, is so well respected. Stephen Mitchell, Robert S. and Ilse Friend Professor of Scandinavian and Folklore, discusses the “phony science” that catalyzed Horsford’s fanciful ideas. Having grown up near the Seneca tribal region of western New York, Horsford picked up some Iroquoian; as such, he “thought he knew maybe more than he actually knew about native languages.” His first mistake was interpreting Norumbega, an El Dorado-like settlement that appeared in the stories of an English sailor, to be a Native American corruption of Norvegia, the Latin term for Norway. Once Horsford had made up his mind that Norumbega was Norwegian, he fell victim to confirmation bias. Mitchell says, “I get the impression sometimes that he just went out for buggy rides on a Sunday and would see things and go, ‘Ah, must be an ancient fort.’”

One of Horsford’s disciples, Elizabeth Shepard, published the highlights of his theories in “A Guidebook to Norumbega and Vineland, or The Archaeological Treasures along Charles River.” She describes Norumbega Tower as a “magnificent and graceful monument to his convictions.” Shepard really did her homework, going so far as to provide page after page of maps crowded with contour lines and tiny serifed labels of the imagined fort and surrounding fishery—but even armed with these, it’s impossible to recognize much more than the river junction and Horsford’s commemorative tower in the modern day.

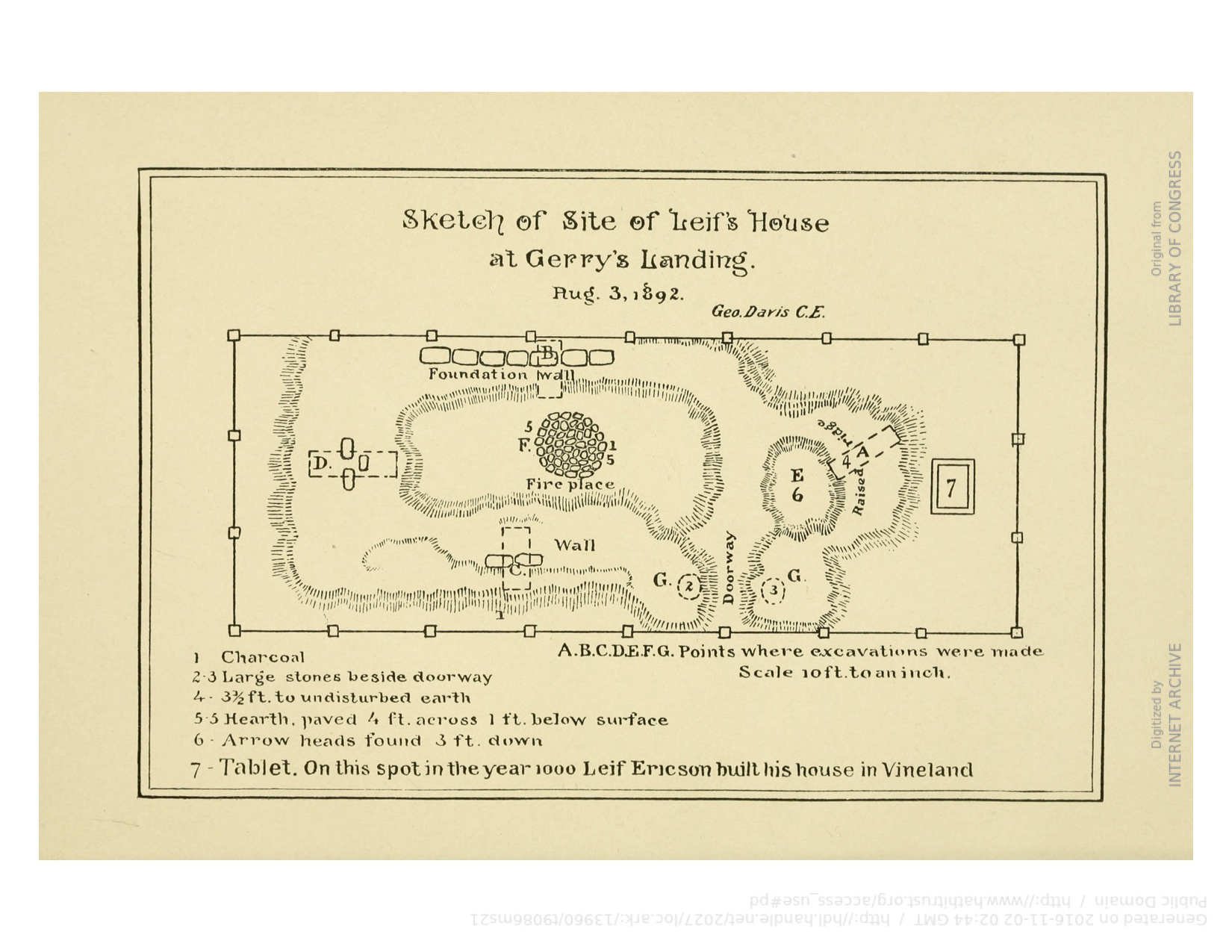

That might be because there’s not a whole lot to see. Upon excavation of the foundations of a house that (he had already decided) was Leif Erikson’s, Horsford uncovered colonial artifacts instead of Viking remnants. No evidence? No problem, with a little imagination. He insisted that Leif Erikson’s ho use was inhabited by colonial settlers many years later, and erased any room for doubt by installing a plaque there: “On this spot in the year 1000, Leif Erikson built his house in Vineland.” The excavation was inconclusive, but his phrasing sure doesn’t sound like it.

Gloria Greis, Director of the Needham Historical Society, views Horsford’s certainty as a vestige from his career as a chemist. In chemistry, “a reaction happens or it doesn’t, something precipitates or doesn’t precipitate, something combines or doesn’t combine.” Where science provides answers, philosophy and history give more questions, and as such, Horsford’s background of scientific rigor did not help him so much as it hindered him.

Horsford lived during the scientific upheaval caused by the publication of Charles Darwin’s “On the Origin of the Species” in 1859 and the social turmoil from the influx of Catholic immigrants in the latter half of the 19th century. The academic community was seeking to redefine the biblical truths it had previously taken for granted, and the Protestant upper class was seeking an American icon besides the Catholic Christopher Columbus. Both parties found what they wanted in the Vikings.

Horsford was relatively progressive, according to Greis: He “saw his wealth as a vehicle for assisting others,” commissioning a public library for Shelter Island in a time when libraries were largely private institutions, donated to Wellesley College even though women’s education was highly controversial, and supporting the suffragette and abolitionist Anne Whitney, the sculptor behind the Leif Erikson statue on Commonwealth Ave. “In all ways, it seems, Horsford is admirable,” Greis says. She pauses. “But then he goes down this strange little path.”

He’s not alone. L’Anse aux Meadows, in Newfoundland, Canada, is these days accepted to be the Vineland that Horsford so wanted to find. Loretta Decker, the Visitor Experience and Product Development Officer for Parks Canada, recalls visitors in full Viking costume paying their respects to L’Anse aux Meadows; once, a woman directed the site’s archaeologist to excavate a certain area in which she claimed to have lived in a previous life.

Decker herself grew up in L’Anse aux Meadows, immersed in Icelandic sagas. The excavation site was uncovered in her grandfather’s backyard. “We used to go up in the hills above the site and berry pick, and I remember looking out and scanning the horizon for those red and white sails.,” she remembers. “I thought that if the Vikings came back, we’d have to get home quick.”

The strange little path from Harvard to Leif Erikson’s plaque winds its way along Memorial Dr., with the river peeking through lanes of traffic. You might find yourself looking across them for those red and white sails. On the approach to the busy intersection near the Cambridge Boat Club, the plaque is barely visible. Naked on the shoulder of the road, it’s both monumental and pitiful, 1,500 miles from home.