Life of Discovery: A Conversation with Matthew S. Meselson

“This molecule is really unlike any other molecule that biologists have ever studied, before or since,” says Matthew S. Meselson, Thomas Dudley Cabot Professor of the Natural Sciences.

The biologist’s past work includes some of the most celebrated advancements in the history of biological research, and any biology textbook would be incomplete without mentioning his accomplishments. Most notably, he discovered the semi-conservative replication of DNA with Frank Stahl in 1958.

Meselson is modest. “In a sense, in this field, everything would be discovered within some short time if it hadn’t been discovered then,” he says. As he speaks, he mimics an unwinding double helix with his fingers.

After observing French biochemist Jacques Monod studying gene expression in E. coli, Meselson created a new method of density gradient centrifugation. Later, when he read about Watson and Crick’s 1953 discovery of the double helical structure of DNA, Meselson immediately saw the application of his new technique to understanding DNA replication. Meselson worked on the project with biologist Frank Stahl, whom Meselson says revolutionized the way that microbiologists study genetics, in what he considers “the most beautiful experiment in biology.”

Meselson was also on the research team responsible for the discovery of messenger RNA, a major component of protein manufacture in cells. Today, he is busy researching sexual reproduction in microorganisms called rotifers.

Meselson, who attended graduate school at The California Institute of Technology, also teaches several Molecular and Cellular Biology courses at Harvard. “I thought it was almost a duty as an American citizen that I had to know something about this very different place - the East Coast,” he says, remembering his arrival at Harvard in 1960. “It really did seem like there was a totally different culture.”

Though he originally intended to stay at Harvard for only five years, Meselson’s involvement in the world of politics kept him on the East Coast for nearly 20. Meselson joined the United States Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, working with former Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger to restrict the use of chemical and biological weapons.

Meselson rarely speaks his own accomplishments without weaving through the vast history of achievements by other great scientists of the past: Mendel, Darwin, Einstein, and his own past mentors Max Delbrück and Linus Pauling, whose black-and-white photographs hang next to Meselson bookshelf. Meselson believes that the essence of science is the ability to appreciate the great discoveries of the past.

“We’re each a link in a chain, that’s what life is,” Meselson says. “The links that preceded you and that will follow you, that’s the way to think of it. We have some idea where it came from.”

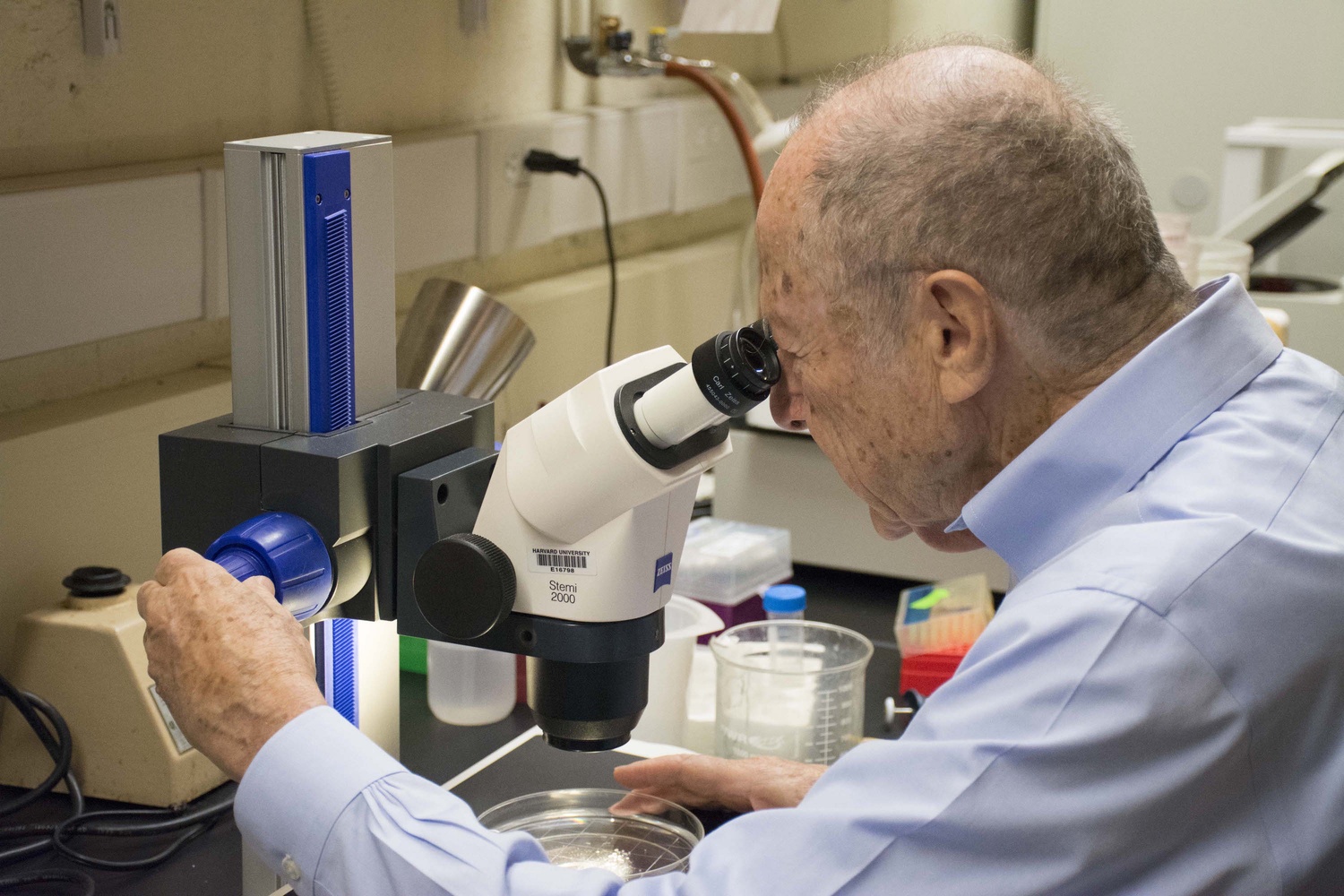

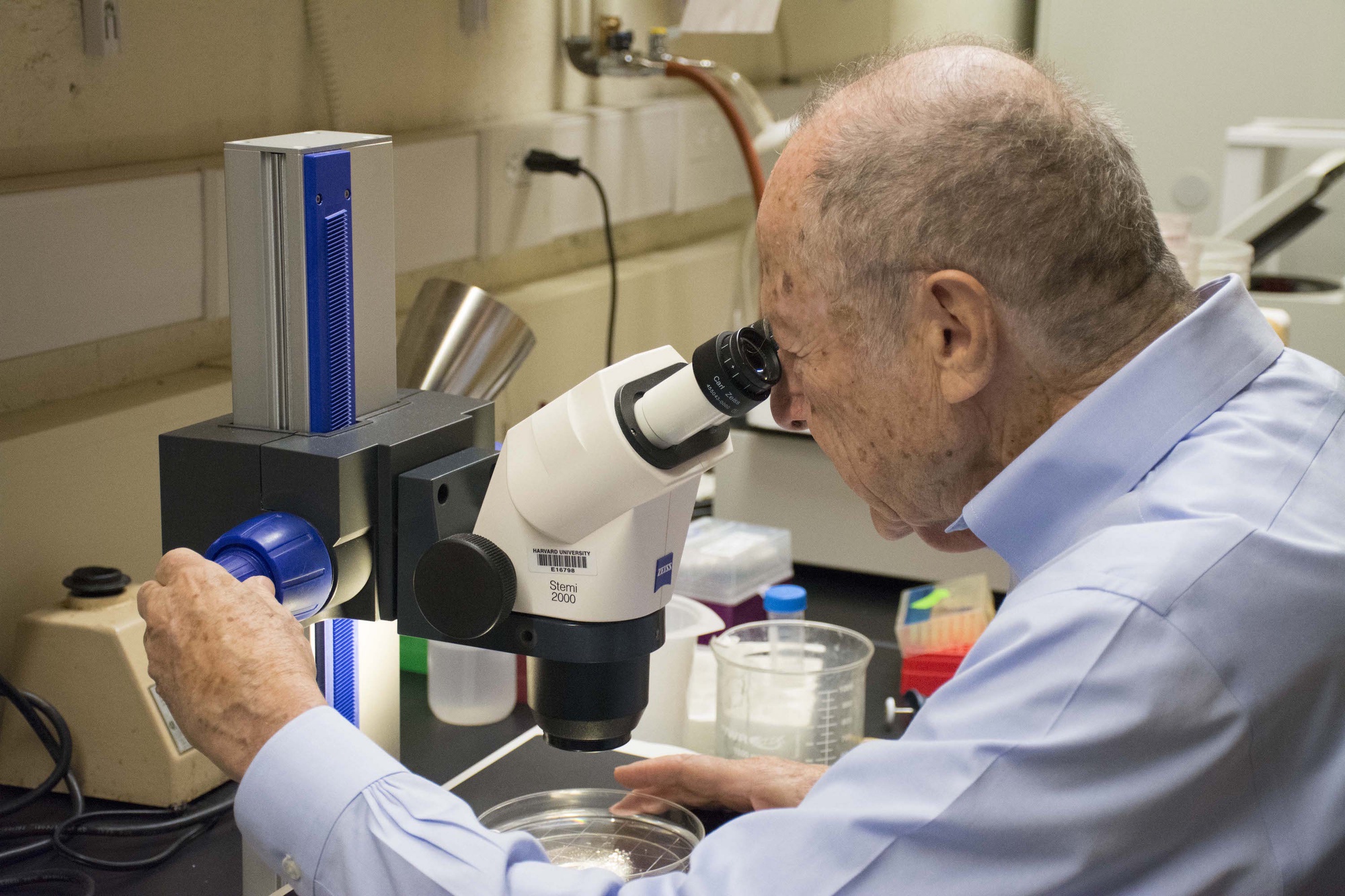

Before we part, Meselson asks me to peer into his microscope. “You want to see the little animals I work with?” he asks, indicating the rotifiers.

“Like any scientist, I’m always thinking about tomorrow’s experiment,” Meselson says. “Where is science taking us? We don’t know. We all feel very modern now, but it won’t last.”