News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

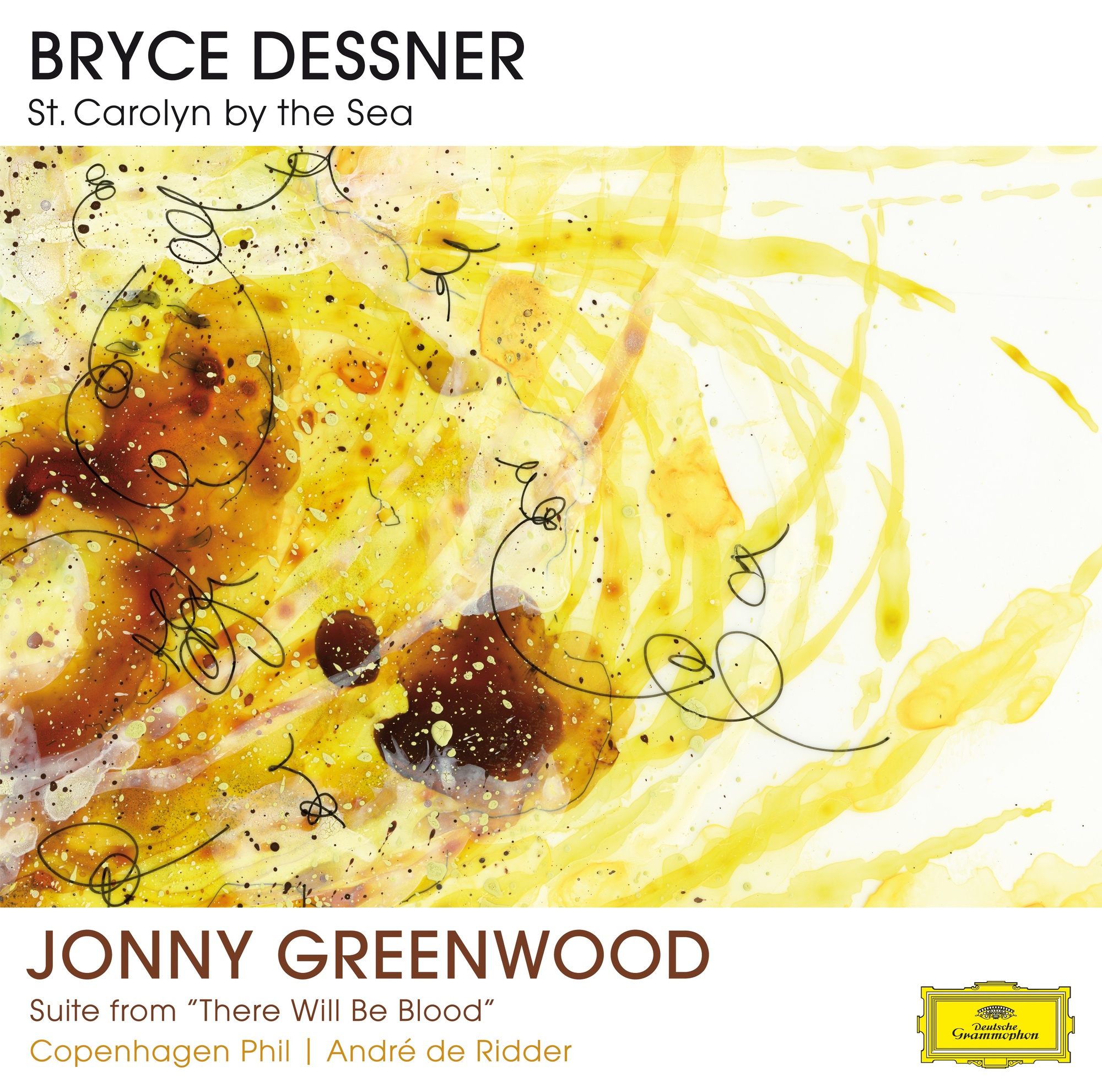

Jonny Greenwood And Bryce Dessner Shine On Classical Split LP

Jonny Greenwood / Bryce Dessner-St. Carolyn By The Sea / Suite From "There Will Be Blood"-Deutsche Grammophon-3.5 STARS

This isn’t the first time two of today’s preeminent guitarists—Jonny Greenwood of Radiohead and Bryce Dessner of The National—have delved into the world of classical music. Greenwood has composed scores for films such as “Norwegian Wood” and “The Master,” while Dessner has collaborated with musicians like Philip Glass and the Kronos Quartet. While not perfect, their upcoming split album—consisting of three orchestral pieces composed by Dessner (“St. Carolyn by the Sea,” “Lachrimae,” and “Raphael”) as well as Greenwood’s “Suite from ‘There Will Be Blood’”—truly highlights the immense possibilities in textures, colors, and emotions that can be achieved when unhindered by the limitations of the rock medium.

The concept of incorporating the electric guitar into orchestral music is not unfamiliar; artists such as The Moody Blues and Jon Lord have already attempted the fusion of classical music with rock, with mixed results. What makes Dessner’s compositions unique, however, is his use of the electric guitar to subtly explore sounds that cannot be achieved with any other instrument. While many other musicians have seemingly combined classical music with rock for the sole sake of jumbling the two together, Dessner incorporates the instrument in a much more nuanced manner. In both “St. Carolyn by the Sea” and “Raphael,” the soft-spoken, mellow guitar part blends with the orchestra so naturally that we sometimes forget the electric guitar is an unconventional instrument for an orchestral setting. At the same time, the various textures it creates are distinct and identifiable. The guitars’ chiming harmonics and surreal glissandos in “St. Carolyn by the Sea” are sounds completely unique to the instrument, providing a fresh element to Dessner’s compositions.

However, the strongest of Dessner’s pieces, “Lachrimae,” does not make use of the electric guitar. Beginning with the soft, staticky harmonics of the cello section, the piece is soon accompanied in stark contrast to this opening by the hollow and somber-sounding violins. Following this haunting introduction, the strings simulate short, heavy breaths by repeatedly playing swelling, abrupt chords punctuating the drone of the string bass section. The more fast-paced, anxious second half of the piece is precluded by the passing along of an initially quiet, increasingly frantic tremolo between each string section. Only after a period of rapid, intense perpetual motion does the piece finally conclude just as quietly and eerily as it had begun. This piece’s attention to detail and nuance makes it evident that Dessner and conductor André de Ridder make a strong team; while Dessner is the messenger, clearly articulating exactly what he wants in his music, de Ridder is the translator, realizing Dessner’s vision through his precise direction of the Copenhagen Philharmonic.

In Dessner’s piece “Raphael,” though, the influence of composers such as Philip Glass and Steve Reich is made almost painfully obvious. Like many minimalist works, Dessner’s compositions primarily rely on the elaboration of recurring ideas throughout the piece. However, its slow, drawn-out pace makes it easy for the listener to get lost or simply uninterested in the music. The development becomes hard to follow at times as well; although Dessner attempts to advance his piece by incorporating extra elements such as violin trills, rhythmic marimba lines, and incessantly rattling percussion, these ultimately distract from rather than contribute to the overall build-up of the piece. Had Dessner paced and developed this piece more gracefully and seamlessly, “Raphael” could have had the potential to be an interesting exploration of a wide variety of textures.

Similarly, Greenwood’s “Suite from ‘There Will Be Blood’” clearly illustrates just how amazingly versatile he is as a composer. From the angry, aggressive march of “Future Markets” to the nostalgic, hauntingly beautiful strings in “HW/Hope of New Fields,” Greenwood’s multifaceted piece perfectly encompasses the many aspects of the film within the duration of a 20-minute suite. De Ridder and the Copenhagen Philharmonic’s rendition of this work also adds an extra dimension previously missing from the original soundtrack—the sharp sforzando accents added to each beat of the low string figure in “Future Markets” creates an even more threatening, aggressive sound than the initial rendition of the piece. In “Proven Lands,” de Ridder also slows the tempo to give the percussive pizzicato and col legno of the strings a cooler, more playful feel that is absent from the original recording.

This album showcases the immense complexity of two musicians not commonly associated with the world of classical music. Both Dessner and Greenwood display a mastery for the orchestral medium, and while Dessner’s compositions are lacking in some aspects, this compilation will certainly be a treat for The National and Radiohead fans interested in observing a different, more contemplative side of these two musicians.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.