News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

Is 31 a Crowd?

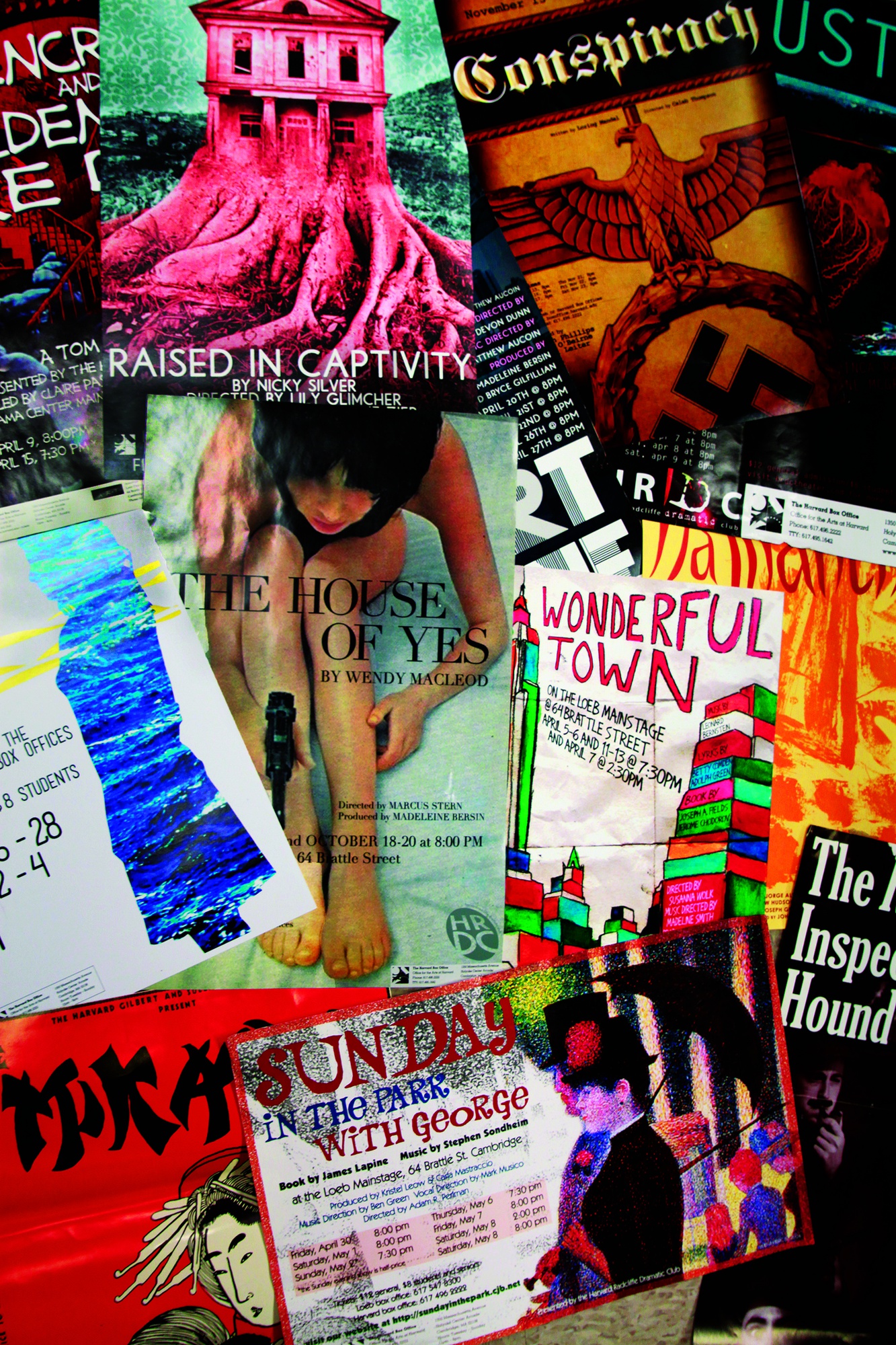

Challenges and Innovation as Harvard's Theater Scene Expands

The vitality of Harvard’s theater community is only increasing, with more shows going up this spring than in any prior semester in recent memory. The stress on the theater infrastructure produced by the unprecedented 31 shows slated for runs this semester has raised important questions about the future of student theater at Harvard: do the current processes for theater space allotment serve the current needs of the theater community? And do more productions on more stages necessarily mean better theater? Meanwhile, the difficulty of procuring space has inspired several groups of students to take their shows in new and innovative directions, seeking out unconventional venues and aiming to present the Harvard community with productions that challenge their conception of on-campus theater.

GROWTH AND CHANGE

There are two central channels for the allocation of Harvard’s stage space: the Harvard-Radcliffe Dramatic Club and the Office for the Arts. The HRDC is responsible for allocating space in the Loeb Drama Center, which has two stages: the large Loeb Mainstage, which hosts two shows per semester, and the smaller, more intimate Experimental or Ex, which hosts six to eight shows per semester. The OFA is responsible for determining which shows will receive space in Farkas Hall and Agassiz Theater, as well as allocating grant funding for productions.

The application process for the spring semester begins in late November with pre-applications, which list director and producer information alongside a synopsis of the show. A full application quickly follows in early December. It includes not only director and producer names but also a full staff list, with positions running the gamut from props mistress to assistant lighting designer. The final step is an interview with the board of the venue applied for, during which board members ask the production staff questions, in order to get a detailed handle on the look and feel of the show. These range from straightforward questions about staff members’ level of experience, to queries directed at directors and designers regarding their creative visions for the show.

“Basically, what the HRDC is looking for is shows that have a really strong vision, shows that we think people want to act in, that would benefit the community, not just the people who are excited about the show and already on staff,” President of the HRDC Alexandra M. Kiley ’14 says. Other factors taken into consideration include the practicability of a show’s design plans, the experience level of its staff, and the completeness of its staff. “One question we always ask,” Kiley says, ‘“Is ‘What is one mistake you made on your last production, and how do you plan on remedying that?’” After a show is approved, the next important step comes at the beginning of the season with Common Casting, when shows hold auditions for actors en masse.

These processes have served the Harvard theater community well for years. However, this semester has seen an explosion of productions—three times the typical number of shows applied for HRDC space, which, even accounting for the typical ebb and flow in the number of productions per semester, is unprecedented. As a result, the typical processes are being strained in terms of both personnel and space.

THE PERSONNEL SCRAMBLE

According to Allen J. MacLeod ’14, director of this spring’s “The Drowsy Chaperone,” filling up the cast of a production can be a challenge. “It’s becoming more and more competitive not just to get space, but once you have space, to get actors,” he says. But perhaps the greatest demand is for technical staff. “Whenever you feel that it is appropriate, you start emailing people trying to compile a team of producers and [a] stage manager, lighting designers, things of that nature, and it’s just sort of an arbitrary system,” MacLeod says. “There’s no set start date. So what you find is that every year people start asking earlier and earlier, ‘Will you be on my team?’”

The struggle to find personnel for productions this season has caused some to feel considerable dissatisfaction regarding the production application process. “Especially because not everyone gets space, you find people signing onto multiple projects, and sometimes it works out that they only get to do one or two, but sometimes it’s like, ‘Oh, the projects I signed onto happened to be up, and I have to set-design for four shows’—which has happened,” MacLeod says. “The system is sort of—well, that’s the problem. There is no system. There is an end goal—to have a team ready by X date—but there is no system. People find themselves overcommitted, under-committed, or scrambling to find people.”

Evan R. Schueckler ’15, stage manager for the recent Dunster House Opera production of “Così fan tutte,” is all too familiar with the demand for technical staff. “I’ve been a stage manager a number of times here,” Schueckler says. “Some semesters I’ve had as many as seven shows ask me to stage manage. The theater community is very stretched for technical staff, and it’s very stressful for people.”

Kiley concurs. “The people who do tech, people like light designers, get about a million e-mails at the beginning of the semester, and it’s a little overwhelming and a little bit stressful,” she says.

Concerns about increasingly early staff recruitment have prompted the HRDC to plan on revising the application process. “The HRDC is looking to...possibly have Ex shows apply with just a producer and director, as opposed to a full staff, and have that staff recruitment process happen after a show [gets space], so that the decision process will be based more on the tightness of the design and the director’s vision,” Kiley says. “With the shows that got space, designers would have a lot more agency.”

Sean K. Hardy ’16, director of the upcoming production “Emilie: La Marquise Du Châtelet Defends Her Life Tonight,” shared his ideas for how the process might be revised. “I feel the way technicians are recruited needs to be something similar to the common casting process…I think it might alleviate some of the stress,” says Hardy. “Right now, it’s a lot for the board, and I appreciate immensely the job they do, and I think that a large vision of the board is to make sure that, as a theater community, with so many separate shows going up each semester, we stay one community.”

BRAVE NEW SPACE

Beyond the strain on the human capital of the theater, there is a second stress: the need for the raw physical resource crucial for every production, space. While it is true that there are more shows being put on this semester, a smaller proportion of proposed productions are getting space. This phenomenon is perhaps most noticeable at the Loeb Ex. Typically, six to eight shows apply for slots in the Ex. This semester, 22 applied. Even with the addition of the “zero-slot”—an extra slot that comes right on the heels of casting and requires shows to hold auditions before winter break—a much higher percentage of shows are being rejected. “It [comes down to] space, “ director of this spring’s “Penelope,” Jacob A. Brandt ’14 says. “There are only six or seven slots in the Ex and two on the Mainstage per semester, and you quickly run into problems with how can you do all this great theater with a limited amount of space and time.”

While there is no easy remedy for the tightness of actors and staff, one reaction to the tightness of space has been to seek less conventional venues for productions. This semester will see increased use not only of the smaller traditional stages on campus like the Adams Pool Theater and the Cabot House Theater, the latter of which is running a full schedule of five shows for the first time in memory, but also the use of stage spaces that are not designed for theater at all.

One such production is Hardy’s “Emilie.” This production will go up in one of the more daring spaces on campus, the so-called “SciBox”: a large-capacity physics lab on the third floor of the Science Center with movable seating. Knowing how tight space was this season, Hardy and his producer S. Jumai Yusuf ’16 had the SciBox in mind even as they applied for space in the Loeb Ex. “We really wanted to bring the audience into this weird, abstract place with ‘Emilie,’ the importance being that we are trying to bring theater to a larger community on campus, namely the scientific community. When envisioning that, we always envisioned ways we could incorporate the space to make it more inviting for people who don’t necessarily come out to see theater,” says Hardy. “It was my tech director, [Max B. Schaffer ’17], who stated that he didn’t think the Ex would be the right space for the play, and I kind of agreed with him, but we weren’t sure what to do.” When asked if he regrets not getting a slot in the Ex, his answer was an unequivocal. “No.”

Hardy says he thinks that the use of nontraditional stages is critical to the mission of the Harvard theater community. “I’m aware that this is a project that could totally fall on its face, and I’m okay with that, because…there is a large debate in the theater community about what it means to have students putting on this art every semester. We know everyone in it, so why are we doing it? So for me, it’s about how you can stretch the confines of theater. And what safer place is there than a student setting, where we’re given all these resources and we’re allowed to fail? We’re trying to test out new questions and try out new boundaries.”

“La Ronde” is a second student production slated to go up this spring that plans to utilize an unconventional space. Directed by Julian A. Leonard ’15 and Daniel W. Erickson ’14, this version of the Austrian play will be sound-based, and will unfold not on a stage, but in a residential building: “Ideally a space with some kind of strong, singular connotation external to the university environment,” Leonard says.

Like Hardy, Erickson believes the use of nontraditional venues for theater enables productions to impact audiences in a unique way. "Bringing an audience into a residential interior, or the basement of a factory, or the backroom of a toy store gives [an] event a very specific framing apparatus to work with,” Erickson says.

The use of an unconventional space also allows a show to comment on what it means to experience theater in a given space. "Part of the appeal of a black box theater, the white cube of a gallery space, or the line of a proscenium is that in theory, these supposed blank slates allow for the world of a piece to be created from scratch,” Leonard says. “But no piece exists in isolation from its cultural contexts.”

CHANGES TO COME?

Of course, there is a second obvious response to the felt need for theater space: building or repurposing structures to meet that need.

“There just seem to be so many people coming into Harvard now that are interested in theater.... It makes sense that more and more people are applying to direct and produce plays,” says Brandt. “And I think that it’s sort of a double-edged sword because…[though] there isn’t great infrastructure for the people who want to do these plays...it’s telling the University that there’s something that needs to be done.”

Hardy agrees that while there is much benefit to using the smaller spaces on campus, infrastructure should be increased to accommodate larger shows. “Things need to change. There needs to be more on campus,” he says. “A limitation of doing shows in space like the black box at the Ex or [in] the Pool is that the seating capacity is smaller.... When you have a smaller seating capacity, and all the theater people want to go to see the shows that their friends are in, you don’t get to bring it to more people. That’s such a shame, because people put their hearts and souls into it.”

Hardy also says he thinks that there should be a change in emphasis for the technical requirement, which requires HRDC members to assist with technical work on a show every semester. In his opinion, it should be oriented towards giving real training, in order to help lighten the burden placed on the experience technical staff members. “I think tech req should be more of a mentoring program, so that if you were to tech req light design for one or two shows, you’re at the light board with the light designer, looking at how they’re plugging cues in, you’re working with them that week, so that it’s less of a ‘I’m not a part of this show, I’m just doing this as a requirement, I’ll screw some things, and that’s that’ [kind of] thing.”

THE SHOWS MUST GO ON

The recent flood of passion into the performing arts is exciting, and rather than abating, seems to be increasing among new Harvardians. “It seems like there is a move [toward] a lot of younger directors applying for space,” Kiley says. This statement is borne out by the large number of sophomore-directed shows, as well as three freshman-directed shows (not including the annual freshman musical), going up this semester.

It remains to be seen what specific measures the theater community will take to adjust to its increased size and activity. But one thing that appears certain is that the upsurge in theatrical activity witnessed this semester will not flag anytime soon. According to Kiley, an imminent academic change is poised to encourage continuing growth in the theater community. “I think [the] trend toward more theater on campus [may also be occurring] because the dramatic arts department is introducing a concentration sometime in the next few years,” Kiley says. “I’m not exactly sure how that will affect the theater scene at all, but it seems that there are more classes being offered, just more excitement on campus about theater in general.”

While the challenges posed by it are numerous, the growth of theater at Harvard is a phenomenon poised to push the bounds of art-making at the college. Student ingenuity and inventiveness has marked this growing period so far and may well continue into the future. The vigorous increase in interest during this transitional period is bound to result in dramatic changes. But the shows will go on—more of them than ever before.

—Staff writer Jude D. Russo '16 can be reached at jude.russo@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.