News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

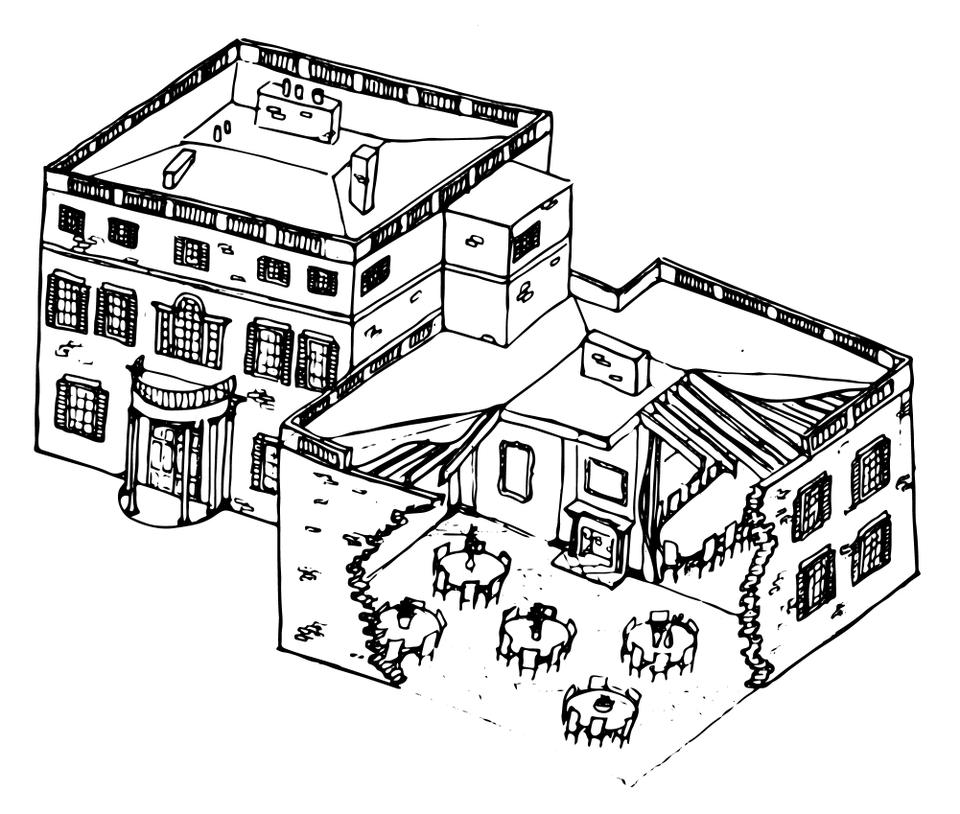

The New Oldest Corporation in America

After a three-year reform process, the first structural changes to the oldest corporate body in the Western hemisphere are nearly complete. A 13th member will join the Harvard Corporation—Harvard’s highest governing body, also known as the President and Fellows of Harvard College—this summer, rounding off reforms that leave the Corporation looking very different from the group that Harvard President Henry Dunster first called to order in 1650.

Facing criticism that the body was disconnected and too secretive, University leaders initiated changes in 2010 to increase engagement with the University community and to allow for more diverse skill sets and opinions.

“We wanted a broader range of expertise, given that the University is so much larger, more complex, incorporates many more dimensions of life than it did in 1650,” said University President Drew G. Faust, a member of the Corporation herself.

Now, with the changes nearly complete, members and university governance experts say that these reforms have been largely successful. Along with its growth in size, the Corporation has expanded its contact with Harvard’s stakeholders by adding members that are increasingly involved with Harvard life.

IN WITH THE NEW

In a December 2009 Boston Globe op-ed, School of Engineering and Applied Sciences professors Frederick H. Abernathy and Harry R. Lewis ’68 criticized the Corporation for lacking accountability, transparency, and the size necessary to govern effectively. As an example, Abernathy and Lewis blamed the Corporation for the University’s loss of billions of dollars during the financial crisis.

“The Harvard Corporation is a dangerous anachronism. It failed its most basic fiduciary and moral responsibilities,” they wrote. In addition to calling for the resignation of “some of its members,” Abernathy and Lewis attributed the body’s mistakes to an antiquated structure.

“It is too small, too closed, and too secretive to be intensely self-critical, as any responsible board should be,” they wrote.

In the spring of 2010, the Corporation launched an internal review of its policies with the creation of a Governance Review Committee. That group released a report at the end of 2010 announcing sweeping changes to the board—many of which addressed the problems identified by Abernathy, Lewis, and other members of the Harvard community.

“This was President Faust’s initiative,” Corporation Senior Fellow Robert D. Reischauer ’63 said, calling her the “prime mover” of the reforms.

That report called for increasing the body’s size from 7 to 13 members, imposing six-year terms limited to two in number, and creating three committees that include Corporation members and other experts.

Since that report, the Corporation has implemented reforms gradually by adding one or two members at a time, avoiding sudden and dramatic change that Reischauer said could have threatened the group’s cohesion.

“A kind of camaraderie develops among that group that facilitates cooperation and yet doesn’t cause people to be reticent in any way. It’s almost like family at a dinner table,” Reischauer said.

Harvard Business School professor and governance expert Jay W. Lorsch said that it is too soon to assess the success of the reforms, but that he thinks that the involvement of more people will indeed result in more productive and informed conversation.

“The intent is absolutely appropriate and I believe it will work,” he said. “I think generally I’m positive about what they’ve been doing.”

A BIGGER TABLE

With a larger group and three new committees dedicated to specific topics, the Corporation has access to a broader base of expertise, talent, and knowledge. Both Reischauer and Faust described this as the reforms’ most important contribution.

In addition to what Faust described as a “noisier conversation” in a larger room at a larger table, Corporation members said that the addition of more members has unequivocally improved the Corporation’s ability to govern.

“I always say, we learn from our differences,” said Lawrence S. Bacow, who joined the Corporation in 2011. “And having people with different perspectives and different experiences on the Corporation just enormously enriches the conversation.”

Higher education is among the areas of expertise that are now better represented.

Bacow, who served as president of Tufts University and as chancellor of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Susan L. Graham ’64, professor emerita at the University of California, Berkeley, join former Duke University and Wellesley College President Nannerl O. Keohane.

“What it means is that there are people who have the capacity to say, ‘Well, there are other ways of doing this, and in fact it’s done differently at other places. Maybe we can learn from them,’” Bacow said.

But a larger Corporation is not the only way that members said reforms have led to more nuanced, informed decision-making.

Three new committees that include Corporation members and other experts—finance, governance, and facilities and capital planning—began meeting in 2011. A committee on alumni affairs and development that works with the Board of Overseers, Harvard’s other, larger governing body, was also created.

“The structure, by allowing us to add non-Corporation members to the committees who’ve been specifically selected because of their subject matter expertise, has just enormously expanded the capability of the Corporation,” said Bacow, who chairs the committee on facilities and capital planning.

He cited Thomas P. Glynn’s participation on his committee as an example of useful non-member participation. As Chief Operating Officer of Partners HealthCare, Glynn oversaw the construction of laboratories for the not-for-profit health care system. Bacow said this experience put Glynn in a unique position to advise the Corporation on similar matters.

“There’s a level of sophistication in the conversation from having them at the table, which is just invaluable,” said Bacow.

BACK TO BOSTON

When University leaders touted governance reforms in 2010, they frequently cited access to a greater pool of expertise as the reforms’ most important goal. Since then, the reforms have improved the Corporation’s engagement with Harvard’s thousands of stakeholders in more ways than directly prescribed by planned reforms. With more members, the board has become increasingly Boston-based and Harvard-connected.

Among the Corporation’s new members are Boston attorney William F. Lee ’72, local businessman Joseph J. O’Donnell ’67, and Bacow, president-in-residence at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education.

Lorsch said that at its inception, the Corporation was composed strictly of members who lived in greater Boston. But, as time progressed and rules relaxed, members began to leave the area. As a result, intimate involvement with the University became more difficult.

With more members working in and around Cambridge and Boston and others traveling to Harvard frequently, it has become easier for the Corporation to monitor the pulse of the University in person.

“That means that they are present and able to come to sporting events [and] to be involved in a variety of activities on campus,” Faust said.

For example, she said, the Corporation’s three Bostonians spoke with staff members and deans at a farewell reception for Education School Dean Kathleen McCartney.

“It was a moment where the permeability of the Corporation was very much in evidence,” Faust said.

Members said that as reforms were being implemented the Corporation increased its communication with administrators and faculty members in more formal ways as well.

“At the completion of Drew’s fifth year as president, a number of us on the Corporation conducted interviews with faculty, staff, and some students also,” Bacow said. “Just to get people’s sense of how the University was doing, and how she was doing.”

Reischauer, who said the Corporation interviewed 106 stakeholders, added that this practice had not been employed prior to the reforms and that he found it “tremendously informative.”

The Board of Overseers—Harvard’s second-highest governing body—also has an unprecedented presence in discussions with the reformed Corporation. Until Reischauer’s appointment in 2002, no Overseer had ever been appointed to the Corporation. Now, four of the new members are former Overseers.

Renewed Corporation engagement with the greater Harvard community transcends traditional governance responsibilities, Corporation members said. They hold informal dinners with affiliates, attend conferences, and give presentations, such as one by Keohane at the second annual Harvard Initiative for Learning and Teaching conference held this May.

BACKROOM BOARDROOM

Though members said that their access to the community has increased because of the reforms, the Corporation remains largely secretive in its operations, and does not divulge its meetings’ minutes.

Corporation members, however, maintain that their counsel is more transparent than it may be perceived to be. Reischauer said that while the Corporation’s deliberations may not be immediately accessible, they are reflected by Faust’s rhetoric and actions.

“Our voice about what transpires at Corporation meetings is really Drew,” he said.

Reischauer said that the Corporation’s recent deliberations have revolved primarily around questions of the budget, facilities planning, and now, the capital campaign. The Corporation seeks to be transparent about these issues, but continues to keep some things hidden when necessary, he said.

“We certainly will try to be as transparent as we can while preserving the ability to provide the University with fiduciary decisions,” Reischauer said.

Still, Faust said that unrefined ideas must be allowed to flow freely for the Corporation to improve and build on them effectively.

“I think sometimes it’s good to be able to have conversations about issues that aren’t fully baked, that may never see the light of day, that are things on my mind that aren’t going to result necessarily in a new program or an action of any sort,” said Faust. “But I think those are conversations that one wants to have without having to have them on the front page of The Crimson. And that is a very valuable aspect of the group.”

Lorsch said he agreed that in order for Faust to fully benefit from the Corporation’s counsel, its conversations should remain under wraps.

“It’s easier to have those kinds of discussions out of the sunlight,” he said.

—Staff writer Steven R. Watros can be reached at watros@college.harvard.edu. Follow him on Twitter @SteveWatros.

—Staff writer Samuel Y. Weinstock can be reached at sweinstock@college.harvard.edu. Follow him on Twitter @syweinstock.

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

CORRECTION: May 30, 2013

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Harvard Corporation Senior Fellow Robert D. Reischauer ’63 said that while the Corporation’s actions and rhetoric may not be immediately accessible, they reflect Faust’s decisions. In fact, Reischauer said that while the deliberations of the Corporation were not immediately accessible, they are reflected by Faust’s public communications.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.