News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

Under the Microscope: Life Sciences 100r

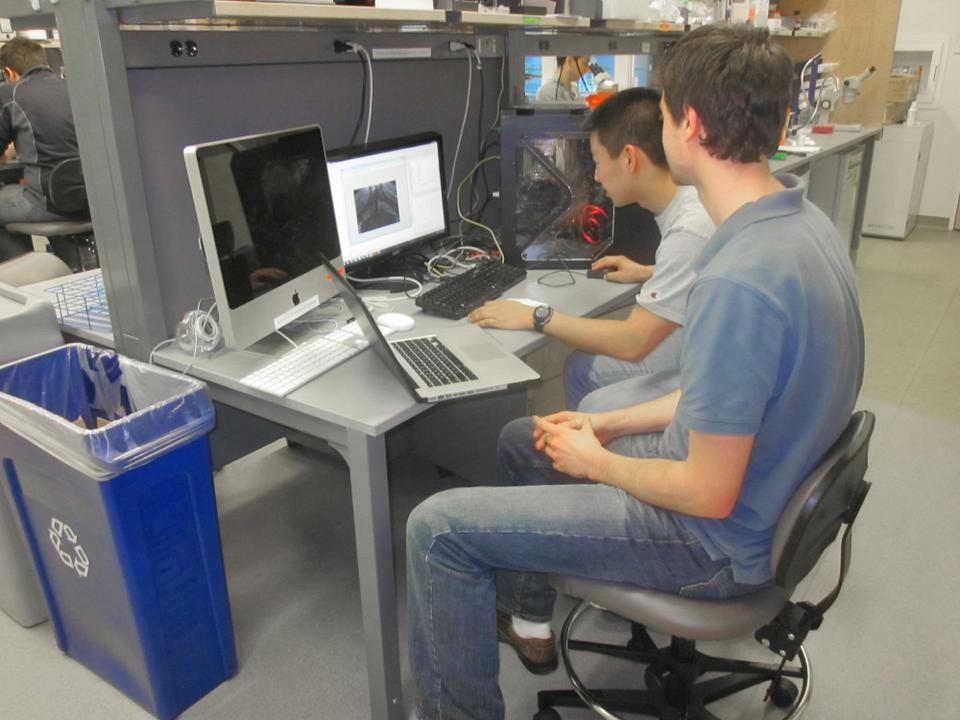

Last spring, while her peers were sitting through Life Science lectures and replicating ages-old science experiments in lab, Valentina Lyau ’15 was learning a little differently. Ten minutes down Oxford Street, Lyau swiped into the restricted-access facilities of Northwest Laboratories to construct a virtual reality as part of a research seminar called Life Sciences 100r.

LS100r is an undergraduate class through which students gain course credit for participating in hands-on research for a semester.

For her research, Lyau aided a graduate student constructing a virtual reality environment for zebra fish to measure neuron activity in response to stimuli.

“It was basically like the movie ‘The Matrix,’” says LS100r professor Alain Viel, who is also the director of the Northwest Laboratories. Viel has directed the course since it was first offered in 2004.

As a fundamental part of the course, undergraduates work with graduate students and postdoctoral researchers, known as “project leaders,” who guide them in their experimentation.

In addition to lab work, students are required to attend weekly meetings, and give three presentations over the course of the semester updating the class on their progress. At the end of the course, the students deliver a public presentation of their semester’s results.

When LS100r was conceived—then as Molecular and Cellular Biology 100r—it was the first research-based course offered for credit at the College. In the time since then, the Life Sciences has created specialized research-based classes, allowing many students to pursue research for credit in labs around the University. But LS100r remains the sole class readily available to undergraduates of all concentrations and all levels of experience.

MAKING TERM-TIME RESEARCH POSSIBLE

Robert A. Lue, head of Life Sciences Education, was part of the team that got MCB100r off the ground 10 years ago. At the time, he was serving as the executive director of undergraduate education in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, and the course was the first at the College to offer class credit for Life Sciences research.

“I knew of no other school that was dedicated to creating a class like that,” Lue says of LS100r. The for-credit class replicated a professional research environment, in which students engaged in projects that appealed to them and worked on a self-determined schedule.

Undergraduate research had been ingrained in the University for years prior to 2004, but LS100r represented the first class to award students course credit for independent research. Following LS100r’s creation and quickly escalating popularity, other concentrations have integrated similar research seminars into their course catalogue, like Chemistry 99 and Psychology 910r.

For many students, offering course credit makes research during the semester a more viable commitment.

One student planning to take advantage of these research opportunities is Doug G. Evans ’15, who intends to enroll in Chemistry 99 next fall in order to invest time in his research without sacrificing from his other schoolwork. This semester, he says, his course load makes it difficult to spend enough time in lab.

“The fact that I will get credit for working in my own lab will definitely be a plus,” Evans says.

Kyle G. Krueger ’14, an applied math concentrator pursuing a psychology secondary, says she enjoys the chance to integrate research into her course load without detracting from her concentration. She is taking Psychology 910r in the process of fulfilling her secondary and says that Harvard’s practice of offering research courses for credit makes it easier for her to engage in the field.

“It’s definitely helpful to get credit for doing psych research,” Krueger says.

LEARNING THROUGH DISCOVERY

“When you do a hands-on experiment and hear something similar in class, then it clicks,” Viel, the director of Northwest Laboratories, says. “It’s putting a face to the concept.”

This approach to learning represents an increasing emphasis on experiential learning as a part of the undergraduate experience. Currently, all nine Life Science concentrations both require a research component and offer independent advanced research seminars.

This curricular requirement demonstrates the high value the Life Sciences Cluster has placed on undergraduate research.

“Just like writing, research is a skill we’re learning by practicing and doing,” says Nicholas K. Lee ’15, an organismic and evolutionary biology concentrator who is currently enrolled in LS100r. “It’s similar to Expos in that we’re learning a skill set, but it’s much more fun than Expos.”

Research classes differ from the type of lab work students see in required or introductory level classes, like Life Sciences 1a and 1b, where students often replicate experiments that have been conducted many times over, and that have specific expected results.

“These are not cookbook projects,” says Lue. “This is current, ongoing research.”

Steve A. Buschbach ’16 is studying mating practices in C. Elegans, a commonly researched nematode, in LS100r this spring. Enrolling in this class, Buschbach’s experience is a far cry from the time-tested drills and tasks most would expect in their freshman science course—the results produced and analyzed by Buschbach and the rest of the student team on the project could shed new light on previously unknown areas of biology.

Lee, the sophomore OEB concentrator, is one of Buschbach’s teammates.

“We’re exploring and asking questions that haven’t necessarily been asked before,” Lee says.

Buschbach agrees, saying, “The idea that we’re finding something that is new to science is awesome.”

Both the students and Viel, their professor, agree that this experience in a lab is essential to a proper understanding of science.

“You don’t really get a sense of how the story unfolds unless you’re in the lab,” Viel says. “Doing research is learning how to combine a certain number of facts into a narrative.”

TRYING OUT RESEARCH

From the beginning, Viel intended for LS100r to be as widely accessible to the Harvard student body as possible.

LS100r alone among research-based classes does not demand any prerequisite courses or research experience. Even non-science concentrators can enroll for a semester.

“It is important to give some students that will ultimately not be scientists the opportunity to experience research,” Viel says. “We’re open to every student regardless of field of concentration or year.”

In the past, the class has had social sciences concentrators as well as a law student who wanted to better understand the experience of lab work before going into the field of patent law. Even within the life sciences, however, many students have never worked in a lab or been exposed to research, so LS100r provides an avenue to explore research without joining a lab officially.

“It’s a great way for students to decide whether or not research is for them,” Viel says.

Buschbach had never done research before coming to Harvard this fall, so he jumped at the opportunity “to know what it was like to do research here,” he says.

And while students in most introductory classes will be exposed to lab reports and learn scientific principles through textbooks and basic lab work, Lue says that any sort of science education is incomplete without a research component.

“No matter what you end up doing, research is what science is all about,” Lue says.

—Staff writer Jessica A. Barzilay can be reached at jessicabarzilay@college.harvard.edu. Follow her on Twitter @jessicabarzilay.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.