News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

Meditating on Mortality

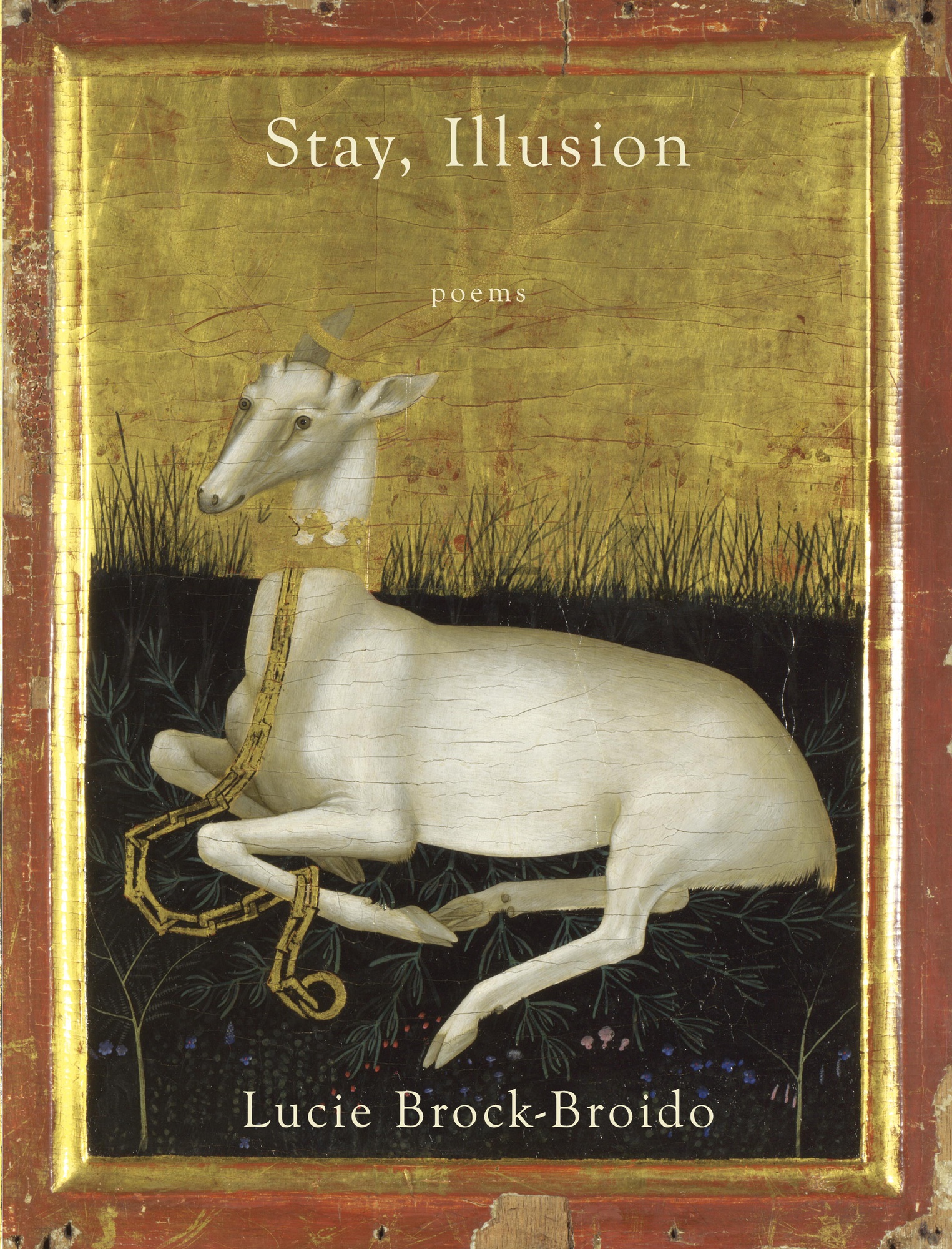

"Stay, Illusion" by Lucie Brock-Broido (Knopf)

The words of Lucie Brock-Broido’s poetry collection “Stay, Illusion” shift enticingly in and out of clarity, reminiscent of the way that the illusions of the past haunt us even as they yield to the immediacy of life in the present. Brock-Broido’s words, however, are freighted with a strong human weight that prevents them from being frivolous. Her book itself, with its insubstantial size, is also an illusion of sorts—a slim volume, coming in just under 100 pages. Most poems are only a page long, with the longest running to three pages, but “Stay, Illusion” is no less profound for its brevity. Brock-Broido writes with an impressive agility of language throughout the collection, delivering short meditation-like poems where each word stands out as an unexpected and yet resonating presence. “Stay, Illusion” performs as a series of poetic autopsies that celebrate and commiserate with the human responses to mortality.

Such autopsies span a great variety of subjects across Brock-Broido’s poems. She inhabits dead social misfits, controversial figures like Glenn Gould and Tookie Williams, and anonymous ordinary individuals like a sheltered Norman monk. In some poems the figure of the poet as herself appears; in others, it is incarnated in an animal. “For a Snow Leopard in October,” for example, is about the soul of a buried lynx who addresses a cub playing in the snow by its grave. All of the poems, despite their variety of human and non-human experiences, are illusions covering the same image: a living soul contending with the chill of death. Fantastic deathbed visions flash in the poems: a haunting example is seen in “Observations from the Glasgow Coma Scale” when a woman tells retrospectively of her comatose state in a way that recalls the uncanniness of Dickinson’s “I Heard a Fly Buzz—When I Died.”

The result, in these works, is often a profoundly empathetic re-coloring of a picture that has already bled out all its ink. One poem has Ophelia, after her death, elegantly delivering a soliloquy that could match any of Hamlet’s seven: “I have made promises I may not keep, go on with my / Soliloquy and was some kind of beautiful.” This dead Ophelia is, if deeply pained, resigned and intelligent. The acute consciousness of mortality, like the mud that sucks Ophelia down under the peaceful flower-strewn surface of the water, is the latent violence under the surface of Brock-Broido’s tranquil language.

Despite this morbid undercurrent, Brock-Broido maintains impressive control of tone throughout her poetry collection. She renders most of her sentences in the form of flat declarative statements. Every poem ends with a quiet period—there is no storming, no trailing off in indecision, no frantic question marks—all is known, as far as it can be known, and what exists is accepted.

Most remarkable of all, then, is the quiet resuscitations and life-affirmations that Brock-Broido creates at the level of her individual words. As a poet, she becomes a courageous hero who gives fresh life not only to dead beings, but also to dead meanings of words. “Stay, Illusion,” as a result, has a distinctive serenity of language. “I was uncertain of certain mythologies, / Invisible as the milk waiting to happen / To the newborn litter of opossums,” she says in one poem. The subtle pun on “certain” changes the rhythm of her sentence, yet it pearls out all the same—uncertain of how it would arrive, but natural and effortless once it appears on the page. She walks through the ages of language, reviving neglected worthy words such as “cummerbund,” “feckless,” and “spindling,” on whom dust has settled for some time, and with a wand she reanimates these words, giving each one new glories and a revivified career. Her words move with grace and solemnity, well-bred, true to their subject matter, and never arbitrary. Yet, it cannot be charged that they are “posturing” either, since they feel uncannily natural and fitting even if one cannot entirely explain or immediately comprehend all of what they mean.

At her best, Brock-Broido has a beautiful touch that is neither too heavy nor too weak—her poems have such a vigorous and historically saturated command of the English language that they might almost be said to impart a tactile sensation. This is most beautifully demonstrated in “Pax Arcana,” her portrait of an Amish maid-servant’s life:

Her linens were chenille and bumpy, worn. Her only jewels were bobby pins.

After supper, after covering the crust of the rhubarb pie with a tea towel,

She retired early to her room. She took off her cotton cap.

She undid the hooks and eyes of her stiff black apron-dress,

Stood reading the chapter from the longsome blue-bound book.

The quiet domestic tone and rich evocation of textures in Brock-Broido’s language makes this poem feel like a verbal rendering of a Vermeer painting. “Pax Arcana” translates roughly from Latin to “Mysterious Peace.” This phrase is, perhaps, the best for describing the whole of her poems—a feeling of timelessness, a reminder that the end of death is beauty.

The first lines of “Lucid Interval” fiercely evoke the wondrous tie between Brock-Broido’s words and her subjects: “Tread very gingerly; you’ve used up almost all the words.” Words, like the breadcrumbs in the tale of Hansel and Gretel or the yarn Theseus used in the labyrinth of the Minotaur, are for Brock-Broido lifelines that must be used as carefully and sparingly as possible. Though an accomplished poet, Brock-Broido has great humility: “Sphinx, small print, you are inscrutable,” she declares in “Infinite Riches in the Smallest Room,” teasing her own poetry as “inscrutable” and of tiny aspect. Another time, she interrupts her poem to say, “I could barely stand to write what I just wrote just now.” For a moment, even the poet herself confesses a fear of being overmastered by the force of her own subject matter. But she must tread bravely on. Brock-Broido is herself in awe of the power she wields through words, even afraid that she may go wrong. But, like living people, she must carry on, conjuring her little words as the only way to battle the vastness of what existed before and will exist after she has said them.

—Staff writer Victoria Zhuang can be reached at victoria.zhuang@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.