News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

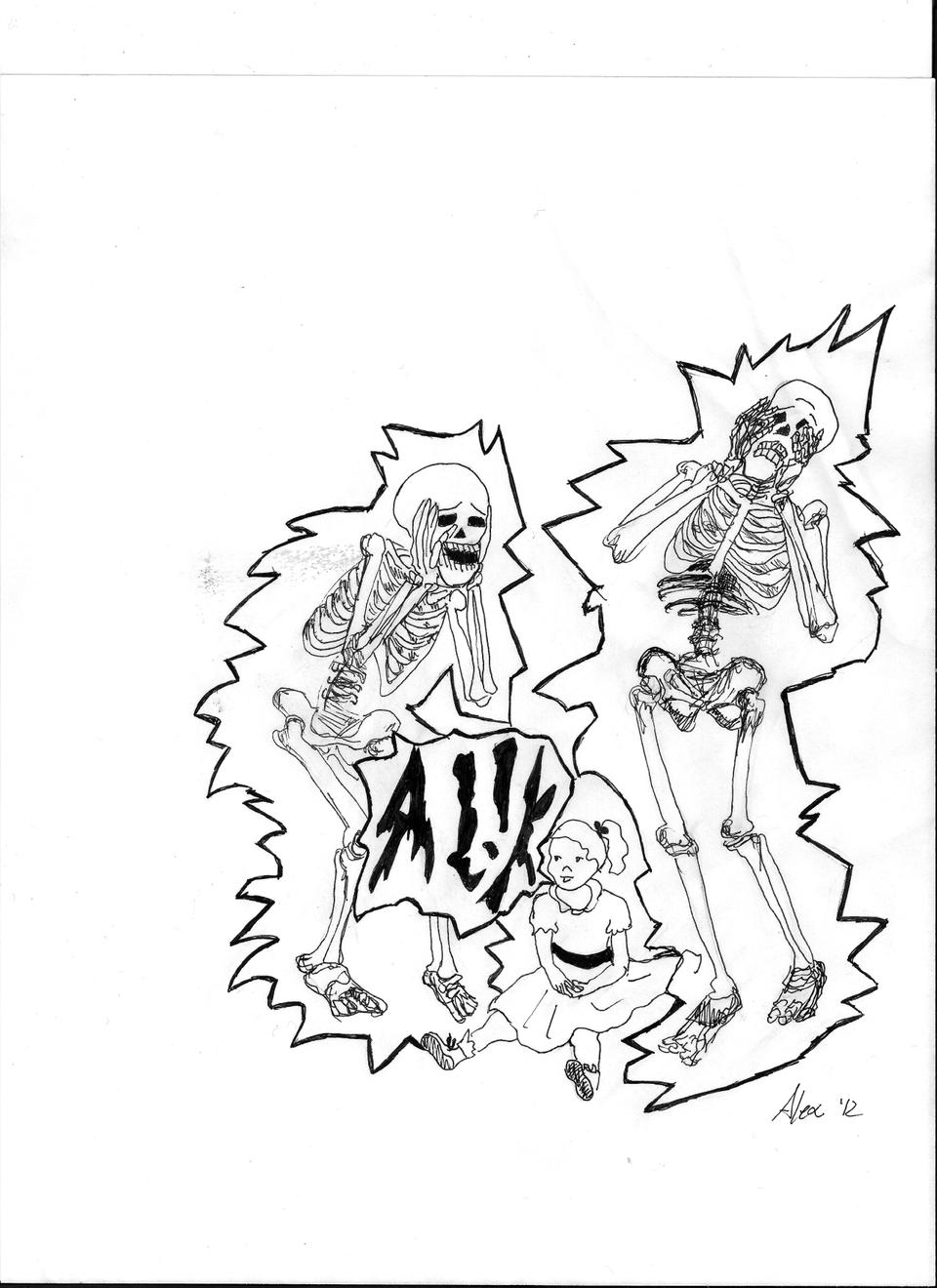

Marcus Imagines Toxic Language in Electric “Alphabet”

"The Flame Alphabet" by Ben Marcus (Knopf)

If you lived in the world of “The Flame Alphabet,” this book review could kill you. The novel opens in the midst of a language apocalypse, in which parents fall deathly ill from the speech of their inexplicably immune children. Author Ben Marcus explores the devastating story of a couple’s struggle with their carcinogenic daughter, alongside the far more complex topic of language as a barrier to religious experience. Despite some strange plot twists, “The Flame Alphabet” is a welcome break from the established dystopian novel: It is alien and complex but sacrificies none of its beautiful turns of phrase for overly scientific descriptions.

Writers of dystopian fiction usually focus on a step-by-step compilation of technical differences between our world and the brave, new one. In contrast, “The Flame Alphabet” uses as little explanation as possible. In most examples of the genre, the setting usually lies in the future so that the reader can fear the coming of a new world, and thus there are countless new technologies that the author can relish in describing—whether Orwell’s “Newspeak” or Bradbury’s wall-to-wall television sets. However, this often leads to a lack of authenticity in character interactions, as the author cogently explains device after device in order to effectively describe the world rather than the characters that move within it. Marcus’ new novel does not patronize the reader in the same way. The first page refreshingly begins with an unexplained description of Samuel’s strange sound-defense first-aid kit—filled with felt, pills, and salts—that he packs when fleeing the deathly voice of his young daughter Esther.

The numerous medical formulas—disparagingly called “painting the insides”—along with the sketchy recommendations of a mysterious expert “Le Bov” lend a foreign quality that permeates the entire novel. As language deteriorates, so does the sharing of information, and Marcus thus creates momentum as the reader knows little about the nature of the disease but more about the protagonist’s overwhelming love for his daughter.

These powerful emotions control much of the narrative focus of the novel. This beginning feels Kafkaesque in that it seems highly strange and cruel for a grown man to sneak away in fear of his young daughter, yet Marcus writes from the perspective of someone whose deviance from the societal norms of our world is self-substantiated. Cognitive dissonance exists only in the mind of the reader, not of the character, as Sam views his departure as merely the next logical step in preserving his life. Marcus explains this wild emotional reaction well, as he meticulously reveals the horrors of the months leading up to the moment where Sam picks up everything and flees. The dialogue is filled initially with the vitriol between Esther—an angst-filled teenager who displays a complete disregard for the impact of language in her interactions with her parents—and Sam, whose language is weak and obliging. His wavering barricade of silence against his daughter is emotional and heartbreaking, as well-written as it is grotesque. He can only love her from afar while he watches his wife Claire collapse from the disease caused by the sheer sound of Esther’s voice.

However, the novel falters when Marcus’ considerable research of Jewish mysticism dominates the action. Sam and Claire both belong to a sect called “Forest Jews,” who listen to the opaque musings of a rabbi through radio wires in the earth in their “Jew Hole.” Besides the dubious connection between Sam’s ability to survive in the new world and the actual Jewish tradition of not converting others—a technique that would invariably involve language—the paranoiac feeling of persecution could have been maintained just as well by the roving bands of children screaming in the streets.

The latter part of the novel is where Marcus truly differentiates “The Flame Alphabet” from other dystopian novels. Sam eventually begins research on creating an alphabet that test subjects can use without dying. It is a wonderful exercise in frustration—and Marcus’s authorial creativity—as Sam explores hundreds of different ways to get around the disease that plagues society. Marcus embellishes this sort of technical detail with the growing disappearance of Sam’s need for language in his new life and creatively imagines a community of similarly silent adults who do not gesture or think; there, Sam develops his own form of prayer. The angst present in the beginning of the book washes away with Sam’s singular goal of creating a new language that won’t hurt so much.

“The Flame Alphabet” would be a philosopher’s apocalypse, but it works well when Marcus devotes so much of the book to linguistic loopholes, keeping the universal emotions center stage. However, Marcus did not need to make a novel with such a strange starting concept overly obscure and far-fetched. As an exercise in futuristic creativity, Marcus’ novel triumphs. A world without language where the inner thoughts of a man are on display is a world fascinating enough, though, without the interspersions of magic realism that distract greatly from the action at hand.

—Staff writer Christine A. Hurd can be reached at churd@college.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.