Cribs: David N. Damrosch

David N. Damrosch, Department Chair of Comparative Literature, joined Harvard’s faculty three years ago. Soon after arriving, he purchased this home on a quiet street behind the Graduate School of Design. He only spends some time here, however: He commutes back and forth between Cambridge and New York, where his wife continues to live and teach.

THE CRIB: A relatively traditional, three-story home. Four bedrooms, three bathrooms.

LOCATION: Cambridge, Mass.

“This is my primary residence—I vote here—but I’m all over the place. I’m there [New York] as much as I am here, so the idea of this was to be a fairly modest place that would be really close to campus,” Damrosch says.

And it is. The house is beautiful and well kept, suggesting traditionalism with a pinch of exotic flair. Amidst spotless living spaces lie relics from Damrosch’s travels, which—considering he works regularly in 12 languages—have been quite extensive.

Damrosch’s travels have defined the way that he lives, taking him to places as far as Iran and North Vietnam. “As a guy of my generation, I didn’t think I’d see either of those places deliberately in my lifetime. But they were very hospitable.”“It hasn’t had time to get too messy yet,” he adds while showing me inside.

THE LIVING ROOM

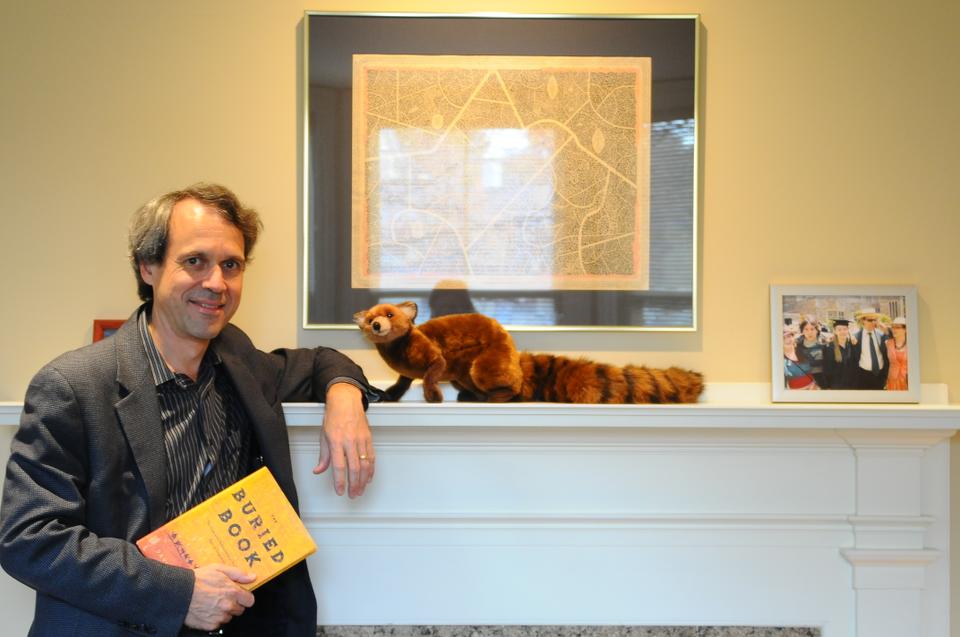

Upon entering, the first striking feature is a stuffed animal sitting on the mantle. According to Damrosch, the brown, furry creature is a mongoose, placed as a reminder of a book that he recently wrote, a discussion of the “Epic of Gilgamesh.”

“I started off a chapter with a king who is really freaked out because he is going out on his chariot and a mongoose runs underneath the chariot. So my wife gave me the mongoose to coincide with the publication of the book.”

But as Damrosch says, “in a way, the art is the most interesting.” Above the mantle, a different sort of masterpiece resides, this one made by Damrosch himself. The hand-drawn circular maze looks as if it could have come out of “The Lord of the Rings.” Perfectly straight lines intersect with each other seamlessly, and the entire design has the feel of an ancient document that should be kept behind glass.

To Damrosch it is just another memory. He drew it as a teenager. “I was obsessed at that time with Tolkien,” he tells me as he points to the ring of gibberish going around the maze. “I think this is one of his [Tolkien’s] poems that I transliterated into Elvish. It took a few weeks.”

Damrosch is next drawn to a watercolor painting on the shelf, made by his mother in the forties or fifties. He explains how he found this particular painting purely by chance. “After she had died, I was cleaning out her house. And everything was gone, and as I was walking out the door for the last time, there was this high shelf where I couldn’t see. And I just put my hand up there and there was this.”

THE DINING ROOM

It doesn’t seem like Damrosch eats in the dining room much, but this space is one of the most intriguing in the house. A series of watercolors painted by Damrosch’s great aunt Helen, his favorite relative, decorate the walls. “She was a very cool lady. Very adventurous. She used to paint underwater, because the fish would lose their color. So she would sketch them in oils wearing a diving helmet, then come up and finish painting.”

Like his Aunt Helen, Damrosch’s other family members have created works of art that are also displayed around the house. He laughs: “In our family the black sheep go into business.” Damrosch himself no longer draws or paints. “The words took over,” he tells me.

After pointing out faded photographs of his great-great-grandfather (who looks surprisingly similar to Karl Marx) and various other family members, he stops at a signed photograph of a man unrelated to the Damrosch family, given to him by Aunt Helen. “Every time I’d go see her, when she was in her seventies, she’d have another story of a different person she knew.”

Damrosch looks at the photo for another second. “So I’m using this to kind of remember her a little bit.”

UPSTAIRS

As he walks up a narrow but elegantly carpeted set of stairs, Damrosch pauses for a moment to look at a framed Gilbert and Sullivan poster in front of him. “My wife and I met in a trial production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s ‘Trial by Jury.’ For my Gen Ed course, I had to decide whether to read Plato’s ‘Republic’ or try out for this production, so I of course made the non-platonic choice. And there I met my wife.”

Turning to his left, Damrosch looks at another piece of art, a picture of a Nefertiti bust from the Egyptian Museum in Berlin. “I took the picture when I was there one time,” he tells me. “I was struck by the fact that she’s enclosed in a glass case. From a right angle it looks as if she’s contemplating herself eternally.” Nefertiti seems to be looking at her own reflection, deep in thought.

After exploring his own study, where he casually points out a framed picture of himself playing Frisbee with Jimmy Carter, Damrosch moves down the hall to the room where his wife works.“

In the Victorian houses, like our place in Brooklyn, everything is set up for the separation of the sexes—two master bedrooms, two dressing rooms. In the modern era, you want one bedroom, but two studies.” Both rooms are quite sparse, the former decorated with boxes of papers and the latter with heavy books on international law.

Yet, sparse would not be a fitting word to describe Damrosch. As chair of the Department of Comparative Literature, he reads, writes, and works with students in many languages. Damrosch makes clear the importance of working in the original language of a text.

“At a certain point, I get frustrated being separated from the text by a translation. At some point you want to get closer to the original.”

This seems to be a metaphor for Damrosch’s lifestyle—he wants to be as close as possible to what’s important, be it his family, his art, or his work. He smiles as he looks out the front window to see the towering Memorial Hall, contemplating his home.“It’s not large, not fancy, but very convenient. We get the Harvard WiFi in the front of the house. We’re really right there, you see.”