News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

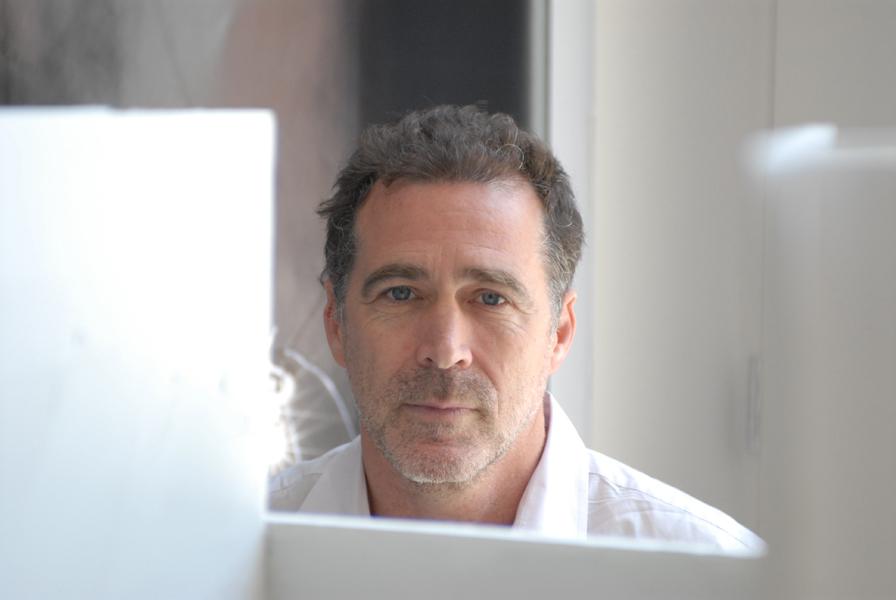

Portrait of an Artist: James Casebere

When looking at James E. Casebere’s work for the first time, one is immediately struck by a sense of puzzlement: is it real, or isn’t it? This confusion arises because his photography, which depicts hand-made miniature models primarily of architectural spaces, falls somewhere in between the realistic and the artificial. Casebere’s often stark constructions tend to tackle social, political, and historical issues, conveying his narratives solely through physical structures. His work has been shown at numerous galleries around the world, including the Whitney Museum of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the Musée d’Art Contemporain de Montréal in Montreal, and the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford, England. A visiting lecturer on Visual and Environmental Studies here at Harvard, he will be giving an Artist Talk presented by the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts on Thursday at 6 p.m.

The Harvard Crimson: All of your work seems to incorporate aspects of two different traditional genres of art—sculpture, or construction of models, and photography. Do you see yourself more as a photographer or a sculptor, and which aspect kind of drives your artistic vision for a new piece?

James E. Casebere: I’m thinking about what I’m working on right now, which is a landscape. It’s actually a model, a big sprawling model of the hills of Jamaica with a beach in the foreground, but with all the rough edges showing. And it’s really a combination of [sculpture and photography], maybe more so than other images which look more seamless. On the one hand, I want to create this illusion of a place and a time—a time of day, an atmosphere—and I want an element of illusion. But because I’m equally interested in the construction itself, I want the viewer to see all the rough edges and to see how the plaster becomes the beach, becomes the hill, or [becomes] the rocks in the water. So that there’s a point at which the illusion and the artifice are clearly a construction and you see both simultaneously, in a somewhat rougher way than some of the “Landscape with Houses” photographs that I’ve done more recently.

THC: Given that you have a recurring theme of the individual versus society, is there a reason you decide not to include any human figures in your models?

JEC: I guess I just don’t see any need for it. When I first started taking pictures, I animated some element of the image so there was an actor in each picture. For example, the first of these constructed photographs that I made was a fan sitting on a pillow in what was supposed to be a living room, and so the fan was anthropomorphized and the actor in the image. Or in another picture there was a fork stuck in a refrigerator, so to a certain extent the fork is a stand-in for...the person. But as I continued to work I wanted to take...the actor/participant out, and put the viewer in, so the viewer would project [himself] into the space instead of standing outside of it looking at someone else. That was the idea.

THC: A number of your works involve flooding your models. Would you mind explaining how this idea came about and how it contributes to the message of your work?

JEC: Sure. Well, it really came about from a trip I took to Berlin in 1998 when I visited Potsdamer Platz after the fall of the Berlin Wall when it was a vast empty plain and look[ed] at all the plans for future development on that site. I picked up a couple of books in the bookstore there that had pictures of the sewer system and the subway system of Berlin as well as the bunkers under the Reichstag, and I think what I was struck by at the time was the optimism and energy and enthusiasm about the future with the unification of Germany, and I just kept thinking about the past. I was thinking about what was lost, and forgotten, and the historic unconscious. So when I first started to make pictures using water, I actually tried to work from some of these pictures of the sewers and subways. The first one that I felt succeeded with water was a picture called “Flooded Hallway,” which looks very much like one of the bunkers of the Reichstag. Water was really about memory and loss, and all those associations—the historic loss, I guess.

THC: It seems like the use of water in your work makes your photographs look less like photographs of physical constructed models and more like paintings. Was that intentional?

JEC: When I started using water I also started using more color, and so I began to think about [the pieces] differently, because the water involved the use of movement and reflection, and in many cases the light that was reflected off the water would break down the structure itself visually. So it became less about the walls and more about the surface plane of the image itself. So yeah, they were more related to painting in that sense. Instead of being about absence and deprivation, they were just the opposite—they became more about overflow, I guess, literally. And you know kind of sensory overload. But visually, they were more about the two-dimensional surface than the three-dimensional space.

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

CORRECTION: Oct. 18

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that James E. Casebere’s talk on Thursday at the Carpenter Center was at 8 p.m. In fact, it is scheduled for 6 p.m.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.