News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

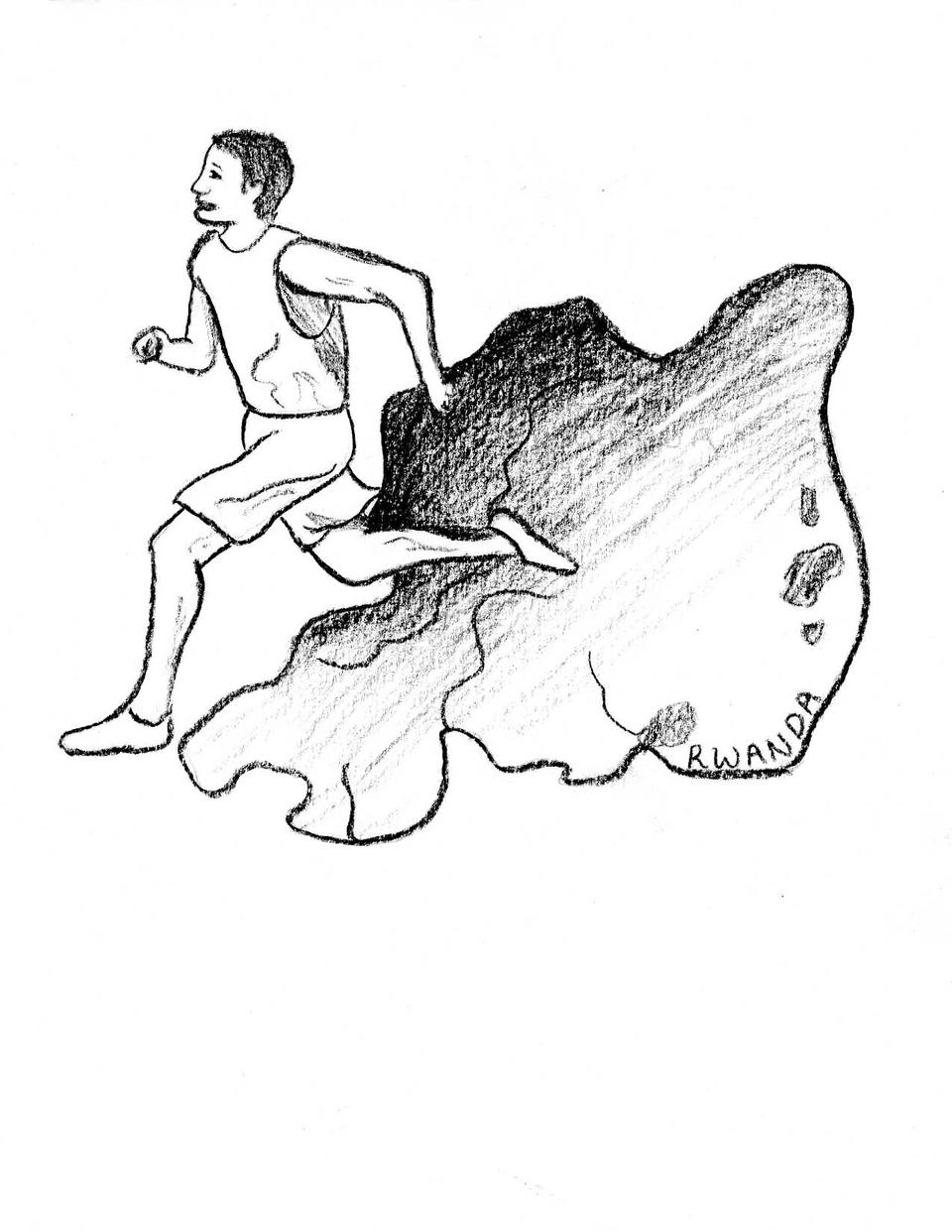

Identity and Loss Run Through Rwandan Novel

"Running the Rift" by Naomi Benaron (Algonquin Books)

It’s Rwanda, 1994, and Jean Patrick—a scientist and Olympic track hopeful—finds himself torn between abandoning his Tutsi identity and risking violence or even death.

In “Running the Rift,” author Naomi Benaron chronicles Jean Patrick’s upbringing and path to college, and through his voice, narrates a personal tale of the atrocities committed in the Rwandan genocide by both sides of the Hutu-Tutsi ethnic rift. Benaron expertly entwines the physical pain of running, the emotional pain of loss, and the somber ache of recovery, in an admirable first novel exploring the travails and resilience of refugees worldwide.

Jean Patrick is Tutsi, an ethnicity Belgian imperialists treated preferentially on account of their supposed higher foreheads, taller statures, and greater wealth. Along with the rest of the country, Jean Patrick has witnessed years of ethnic conflict following the Belgians’ departure. Even personal relationships are not safe from the tensions; Jean Patrick’s brother joins a coalition of Tutsi rebels, while Jean Patrick falls in love with a Hutu girl, thereby endangering both of their lives as well as her family. He must obtain a fake Hutu identification card in order to travel safely and leave school grounds to run, leading him to question the morality of abandoning his family’s ethnic heritage.

Themes of identity, anger, and forgiveness coalesce seamlessly in Benaron’s novel. Her background as an author of short fiction is apparent in the structure of “Running the Rift,” as the novel is composed of many short scenes, each rich with imagery, that help to connect the numerous themes. Some scenes are two lines, while others last a chapter; this literary convention allows Benaron to play with time, stretching the painful moments longer or abbreviating scenes that Jean Patrick would have wanted to block out of his memory—like when Hutu fighters drag a family of Tutsi from hiding and beat them to death while Jean Patrick hides “close enough to reach out and touch them.” Truncated in both length and description, Jean Patrick’s experience stands out as much for its violence as for his desire to forget these horrors. Benaron also lengthens time when Jean Patrick remembers certain haunting events, dwelling on particularly painful moments such as his return to his childhood home, where he unearths human bones from destroyed huts.

Jean Patrick’s track races, an integral element in the narrative, exhibit convincing dramatic depth, in part because of Benaron’s personal experience as an Ironman triathlete. She describes the peculiar feeling of pushing oneself to the fullest and also realizing the physical limitations of the human body, “as if there were two of him, the runner of his spirit, who could fly, and the runner of his body, who teetered on the edge of surrender.” This contrast—of almost escaping and of knowing the fragility of a human life—is a theme that recurs throughout the novel. Just when Jean Patrick seems on the brink of happiness or of outrunning his competitors, the civil war returns and ethnic conflict brings violence to his friends and family, irrevocably changing the world around him.

Nearly two decades have passed since the Rwandan genocide, and countless books, both fiction and nonfiction, have been written about the conflict, allowing the world time to reflect on actions taken by both factions. Benaron tries to bring closure to her characters, yet coming to terms with the murder of his countrymen will clearly haunt Jean Patrick for the rest of his life, as it likely haunts many of those who have survived the genocide.

Benaron visited Rwanda for the first time in 2002. There, she met Mathilde Mukantabana and Alexandre Kimenyi, two Rwandans who shared their stories and helped to shape many of Jean Patrick’s struggles. Despite Benaron’s limited exposure to Rwanda during the time of the genocide, Jean Patrick’s story contains a great deal of truth alongside invention: many of his experiences are drawn from Benaron’s talks with Rwandan refugees. Benaron dedicated her novel to her two vital contacts and “all the survivors...who lent me their voices.” The sheer number of voices in “Running the Rift” lends substance and authenticity to this powerful novel, artfully encompassing conflict, danger, and identity.

—Staff writer Virginia R. Marshall can be reached at virginiarosemarshall@college.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.