News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

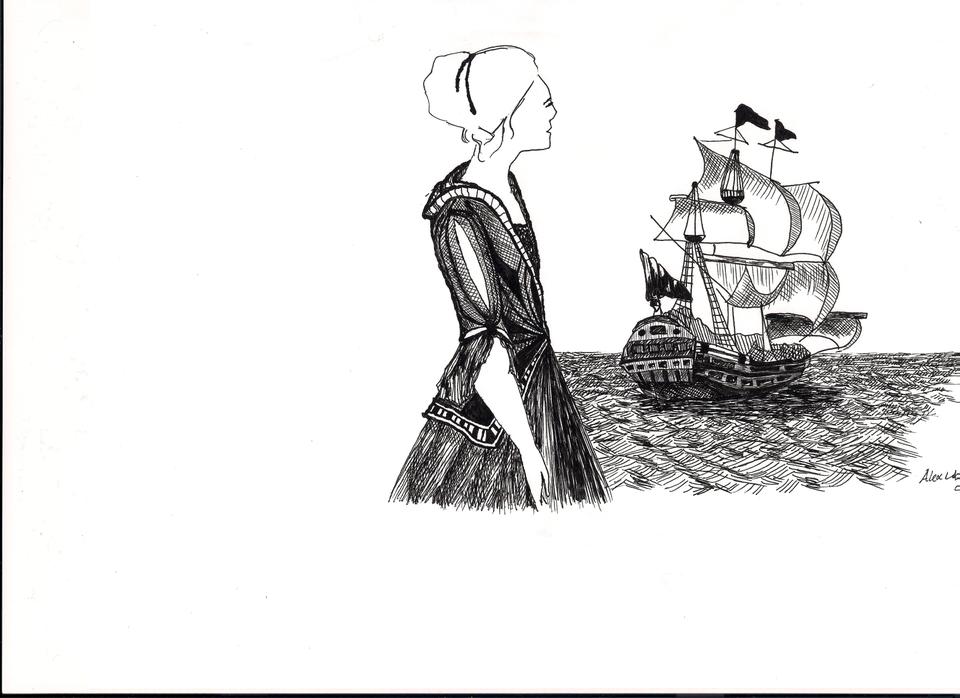

Jensen Expertly Navigates Life in a Danish Port Town

'We, the Drowned' by Carsten Jensen (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

From Denmark to America, and from Hawaii to the Congo, Carsten Jensen’s “We, the Drowned” is global in its reach. But at the center of this wide-ranging sea drama is the town of Marstal, and the stories of its native sailors, widows, and children. Translated from the Danish by Charlotte Barslund and Emma Ryder, “We, the Drowned” is not the tale of one single man or indeed of one single sea venture; the real protagonist of the novel is Marstal itself. Jensen deftly illustrates the effects of time, progress, and war on the small port town as he chronicles its generations from the mid-19th century through the Second World War.

As he recounts the lives of sailors, warriors, and boys and their mothers, Jensen narrates from the perspective of the people of Marstal—the “we” for whom the book is named. These voices are present throughout, casting judgment on the figures that loom large in the history of the town—Laurids Madsen, who flew up to heaven and came back in his boots; Madsen’s son Albert, who undertakes a Telemachus-like quest for his disappeared father; Herman, murderer of man and seagull; and Klara Friis, the widow who dooms the men of Marstal even as she tries to free them from their enslavement to the sea.

The plurality of the narratives that Jensen presents does not, however, distract from the development of his focal characters. At times, the plural voices of the Marstallers recede in favor of other kinds of narration. The most gripping single narrative of Jensen’s novel—Albert’s quest to find his father—is presented as an extract from the sailor’s private journals, and so is told in the first person. Thus Jensen is able to detail Albert’s personal reactions to the shrunken human head—“Jim”—kept by his captain, the blue, tattooed faces of the Kanak crew, and the strange attack on the ship by clouds of thirsty butterflies.

But the collective voice of the Marstallers is never silent for long as they report on the struggles of each new generation. The lives of Marstal men are lost to both sea and war, although Jensen makes a clear distinction between the two fates. Boys grow up knowing that they are likely to die with their boots on—that is, by drowning—but war is another matter entirely: “What was the difference? The difference was that the sea respected our manhood. The cannons didn’t.” Jensen does not glorify naval war; through the eyes of the Marstal men, he reveals naval wars to be terrifying, dirty, and foul. These men are rarely fighting for a cause in which they believe deeply. Rather, they seem caught up in the winds of a wider world controlled by powers such as Germany, Britain, and America.

But sea battles are not the only ones fought by the people of Marstal. Jensen’s collective narration is most convincing when it is from the vantage point of the boys of Marstal, who face their own smaller terrors. In some cases, their trials arrive in the shape of other boys as they form gangs and compete with one another in games of war. In other cases, the boys band together against a common enemy: Isager the schoolteacher. But it is when they join into one mob that they reveal that the world of children can be just as brutal as the world of adults, though on a smaller scale. One of the more distressing moments in the novel is not the death of a man, but rather the death of the schoolteacher’s dog at the hands of the vengeful boys.

If Jensen is at his most heart-rending as he illustrates the cruelty of the boys of Marstal, he is also at his most eloquent as he describes the experience of boyhood. “Every summer,” he writes, “we went to the beach, with its border of dried seaweed that crackled and pricked under our bare feet, its carpet of crushed mussel shells, its luminous green seabed, and its swaying submerged forests of bladder wrack and eel grass.” Jensen is masterful at evoking the landscapes of his novel, whether the idyllic summer world of Marstal boys or the pitching deck of a ship beset by a gale.

While the exploits of men dominate the novel, Jensen is also careful to include Marstal’s female residents, whom he depicts as perpetual widows: “Our women, who have no choice but to stay behind in Marstal, live in a state of permanent uncertainty. Even a letter is no proof that the sender is alive; it can be on its way for months and the sea steals men without warning.” Jensen shows generations of women taking up widow’s weeds—but their roles are not quite as passive their lives of widowhood might suggest. There is Cheng Sumei, the woman behind the decisions of businessmen and shipping makers alike; there is Kristina, who travels the world on a boat her father named for her; and there is Klara Friis, who after losing a husband to the sea tries her best to ruin the town’s seafaring industry so that her son might not share his father’s fate.

A novel like this one, which spans two centuries and covers the globe, might run the risk of being overly broad. But it is the large scope of Jensen’s novel that gives the work its strength. Jensen does not romanticize the life of the seaman or the world of this small port town. The lives of the Marstallers are rough; over the course of two centuries they face the dangers of three wars, the loneliness of widowhood, and the terror of being left behind in a changing world. But the sea, despite the efforts of Klara Friis, is the only constant in the lives of the Marstallers, serving both as the source of their livelihood and, in the case of many of the ‘drowned,’ as their final resting place.

—Staff writer Rachel A. Burns can be reached at rburns@fas.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.