News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

The Maestro's Medley

Opera’s fusion of multiple art forms drives efforts to revitalize the art

In an 1849 essay on aesthetics, German composer Richard Wagner popularized the rather unwieldy term “Gesamtkunstwerk.” According to Wagner, a Gesamtkunstwerk, or a ‘total’ work of art, is the highest attainable artistic ideal, a work that synthesized all the major art forms in a single theatrical performance. Fittingly, Wagner applied this term to the multidisciplinary elegance of opera, which unites so many different artistic inputs into one totalized performance.

Indeed, the artistic amalgam that is opera combines instrumental music, singing, dialogue, and dance to create a multisensory spectacle that may appeal to an audience on multiple aesthetic registers. The viewer may both latch onto the particular art contained within opera that they most appreciate and also experience Wagner’s idea of operatic synthesis.

While not the most popular art form at Harvard, students and graduates are revitalizing opera by performing famous works at Harvard, honing their skills in activities on campus and abroad, and composing works of their own concerning modern life. They aim to prove that opera, though steeped in tradition, is accessible and relevant.

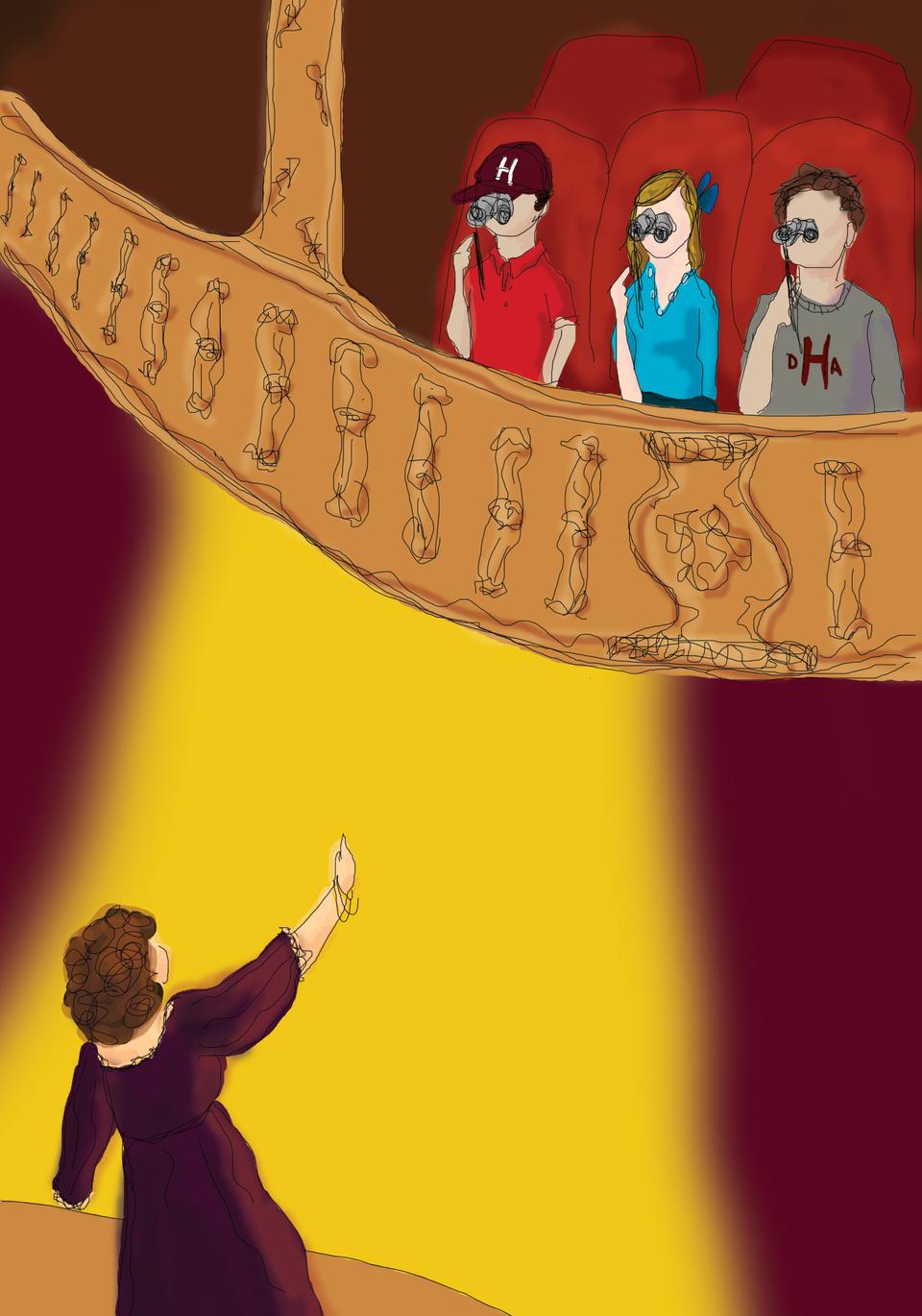

DIE BAGELMAUS

In the Dunster House dining hall, it’s brain break—the Harvard event that most unites disparate social elements on campus. Overworked student writers, scientists, and athletes intermingle to enjoy cold bagels, old cereal, and, tonight, something completely different. The bewildered crowd, suddenly surrounded by tuxedo-clad actors and frantic musicians, is witnessing the start of dress rehearsal for “Die Fledermaus,” Johann Strauss’ classic work being put on by the Dunster House Opera (DHO). Rather than flee to the opera-free safety of their rooms, however, residents of the house linger a little longer than usual over brain break to see what all the fuss—and noise—is about.

Getting people to go see the opera of their own volition, unsurprisingly, is no easy feat. In some fundamental sense, opera seems unsexy: fat women in gowns stereotypically stand in for action heroes in swimwear; topics of convoluted aristocratic manners and tragic romance appear pitifully outdated; and, worst of all for an American audience, most great operas were not originally written in English. Benjamin J. Nelson ’11, musical director of the Harvard a cappella group the Krokodiloes and star of “Die Fledermaus,” claims to be languishing idly the afternoon before “Fledermaus” opens. However, he answers my questions with bounces and nervous, energetic exclamations. “Opera, whether deservedly or not, intimidates a lot of people, [whereas] a cappella reaches the point of accessibility at which it’s almost annoying,” he says. Indeed, the light-hearted, almost silly nature of a cappella does seem the ultimate contrast to opera’s beauty and renowned history. A cappella concerts are short and audience members know exactly what to expect, while “Die Fledermaus” is more than two and a half hours long and, for the average Harvard student, utterly recondite.

OPERATIC PHILOSOPHIES

The DHO is sensitive to these barriers associated with opera. In order to make their material accessible and appealing to undergraduate audiences, they have a stringent set of criteria for selecting an annual opera. The first of these is that the opera must either be written in English or have a readily available English translation. While this decision does limit the number of available options, it vastly increases access, both for audiences and performers. “I think it’s really great that DHO performs in English,” says Nelson. “I personally would never have auditioned for the show if it hadn’t been in English.”

Cast size is also a factor in selecting an opera. Many operas have one or two title roles and a limited supporting cast. The DHO looks for shows with a decent number of roles as well as a substantial chorus that allow them to cast more performers.

One of the greatest obstacles to performing opera at an undergraduate level is that many of the most famous and recognized roles are infeasible for younger, less developed voices. The corpus of Giuseppe Verdi, for example, is off limits to DHO. “A lot of the operas that I was initially drawn to … were just completely impractical,” says Matthew C. Stone ’11, a Crimson arts editor and stage director of “Die Fledermaus.” “Vocally it would be too taxing for young voices to sing any really heavy operatic repertory.” The human voice does not reach full maturity until the late twenties.

While theater companies on campus can perform well-known shows that will attract audiences, opera companies like DHO are more restricted. “You have to look for lighter fare, or lyric opera, or chamber opera for undergraduate voices,” says Stone. Thus, careful thought goes into selecting an opera that is both practical for college-aged performers and attractive to a college audience.

Lowell House Opera (LHO) takes a radically different approach. Its auditions are open to graduate students and actors outside the Harvard community, and it has more relaxed criteria for selecting operas to perform. Last year, the Lowell House Opera performed Giacomo Puccini’s renowned “Tosca” in Italian with English projections, and almost all its singers were professional. “Historically [the DHO and LHO] perform rather different repertoires,” says music director and conductor of “Die Fledermaus” Matthew A. Aucoin ’12.

This difference amounts to a difference in philosophy: characteristically, the DHO focuses on accessibility in the Harvard community and the LHO focuses on performing the greatest operas in their traditional forms. “I think Harvard’s got the whole spectrum,” says Aucoin.

ARE YOU EXPERIENCED?

This operatic spectrum extends to the level of experience held by the cast in student operas. “Most people who get really involved with opera here don’t come from ‘operatic backgrounds’ because those are really rare,” says Aucoin. Instead, students approach opera having trained in theater or classical music. Jennifer Chen ’11, the current president of the Dunster House Opera, came to the form through her involvement with the Early Music Society of Harvard, which is devoted to the performance of historic Western music.

Though Aucoin now has a good deal of professional experience, he was mostly self-taught before coming to college. Last year, he composed and conducted his own opera, which was based on James Merrill’s epic poem “The Changing Light at Sandover.” His opera, which he describes as “a supernatural love story,” premiered in the Horner Room of the Agassiz Theatre and was cast from a largely undergraduate group. Aucoin has also become interested in conducting, and is studying the art with director of the Harvard-

Radcliffe Orchestra Federico Cortese. Last summer he received an Artist Development Fellowship to study conducting in Milan and Florence.

Other performers in “Die Fledermaus” have also studied opera formally. Sofia M. Selowsky ’12, who plays Prince Orlofsky, has been singing opera since fourth grade. She also received an Artist Development Fellowship to do opera training in Salzburg this summer. But as DHO holds auditions through common casting, many cast members do not enjoy this high level of background experience.

SENSORY SYNTHESIS

As these performers take the leap to try opera for the first time, so too may Harvard students. For those willing to try something new, the rewards are numerous. Opera as a genre is not just about music; rather, it is a confluence of many artistic disciplines. “Opera offers a unique combination of dramatic, musical, and visual experiences,” says James Edward Ditson Professor of Music Anne C. Shreffler. One performance stimulates a gamut of aesthetic sensibilities. Audience members do not go to ‘see’ or ‘hear’ an opera, but rather to ‘experience’ one.

Opera streamlines elements of dance, theater, and vocal and orchestral music into one performance. “What is opera but a fusion of all these different art forms?” says Aucoin. This fusion is fundamental to opera and makes performing one a hefty challenge, especially for undergraduates working with limited resources in terms of space, funding, and experienced performers.

This difficulty requires that a multitude of individual efforts go into the creation of the final operatic product. At DHO’s dress rehearsal, violinists are bent intently over their sheet music, while onstage Nelson makes a flamboyant entrance and bursts into song. “That all of these people come from one undergraduate college’s student body is pretty amazing,” says Aucoin, who himself must be fully absorbed in conducting the orchestra while also intimately attuned to how the people onstage are moving.

CAPABLE CONDUCTION

Because opera is a combination of so many different art forms, conducting one is something of a balancing act. Aucoin says that to conduct successfully, “you have to do everything and nothing.” This paradox captures the conductor’s subtle but crucial role in coordinating dramatic action with music. Aucoin’s job obliges him to communicate subtle changes in the mood of the singers onstage to the musicians seated below in the pit. “You have to make everyone feel comfortable, but you can’t get in the way,” he says. Aucoin emphasizes the importance of allowing singers’ spontaneity to flourish, describing the conductor’s role as “a conduit for the energy of the show.” In opera, because so many things are happening simultaneously, it takes only a small error to derail the entire production. This makes the conductor’s position a tenuous one. “Everyone has to be on their A-game all the time,” says Aucoin.

From a staging perspective, opera is more demanding than a stage play because there are in effect two texts to work with: the libretto, or actual text of the opera, and the musical score. “The music becomes something you have to engage with from a staging standpoint,” says Stone. The director took his cues from the music more than from the text, listening to the score in order to isolate the emotions of a particular scene. The large amount of material, both musical and technical, necessitates a greater degree of choreography than is generally required in theater. “It’s inherently useful, going into a scene, to know what is going to fill every bar of music,” says Stone.

ATTRACTING ATTENTION

Professor Shreffler, who has been teaching a seminar on opera at the Humanities Center for seven years, believes that the inherent difficulties and obscurites of opera can be overcome by engaging Harvard students with the form, particularly due to the resources surrounding the University. “Boston is a powerhouse for scholarly research on opera,” she says. The city is home to the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Boston Baroque—both of which are full orchestras that perform the musical scores of operas—as well as the Boston Lyric Opera.

In her years of teaching the seminar in conjunction with two Tufts University professors, Shreffler has seen that opera can connect with both personal tragedy and the political landscape in a modern context. She cites the discussion topic of last week’s seminar, an ongoing production by the Boston Lyric Opera of “The Emperor of Atlantis.” Composed by Jewish-Czech composer Viktor Ullmann in a concentration camp during the Second World War, it is a thinly-veiled, satirical critique of Hitler. For a Boston Lyric Opera performance, it has received extensive media attention, including a review in the New York Times. “This opera, because of the human interest story, the quality of the music, the fact that it’s not so well known, that it’s not another ‘Tosca,’ has attracted a lot of attention [from the media],” says Shreffler.

In addition to the Humanities Center seminar, Shreffler teaches an undergraduate course with Professor of Music Carol J. Oja on the operas of John C. Adams ’69, who is best known for composing “Nixon in China,” an opera chronicling the former president’s 1972 trip currently running at the famed Metropolitan Opera in New York. Like Ullmann’s work, Adams’ demonstrates opera’s potential for political relevance. There have been so many new political operas since that this new body of work is being referred to as ‘CNN opera.’ “Nixon in China” has a deep Harvard connection, which is part of the reason why it is such a focus in Shreffler’s course. In addition to having been written by Adams, the opera is being directed at the Met by Harvard graduate Peter M. Sellars ’80, and Alice A. Goodman ’80 wrote the piece’s libretto. The Dean’s office has provided funds for students of the course to go see the production. “There are a lot of composers interested in writing operas about current events, and I think that helps to make opera relevant,” says Shreffler.

Aucoin witnessed firsthand the contemporary significance of opera during his time at La Scala in Milan, perhaps the world’s most famous opera house. Aucoin’s stint at La Scala coincided with Italian government’s dramatic cuts for funding of the Arts. “Things were in total chaos,” says Aucoin. “Apart from getting a musical education I got to see the inner workings of a very chaotic time in Italy’s musical history.” People were protesting outside the opera house in large numbers, a testament to the important position opera holds in the popular artistic sensibility of Italy.

CREATIVE TOTALITY

What about opera affects people so profoundly that they are moved to protest when its survival is at stake? Perhaps arguments for the form’s unique creative totality imply an otherwise unattainable artistic access. “It spans the whole range of human emotion,” says Shreffler. The artistic breadth in operatic form, then, may expand the aesthetic possibilities of its content. Harvard academics and performers seek to instill this message to a campus that needs only to listen.

—Staff writer Anjali R. Itzkowitz can be reached at aitzkow@college.harvard.edu.

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction.

CORRECTION: FEB. 16, 2011

The Feb. 15 article "The Maestro's Medley" incorrectly identified the composer of "Die Fledermaus" as Richard Strauss. In fact, the work was composed by Johann Strauss.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.