Race, Gender, and Politics

I.

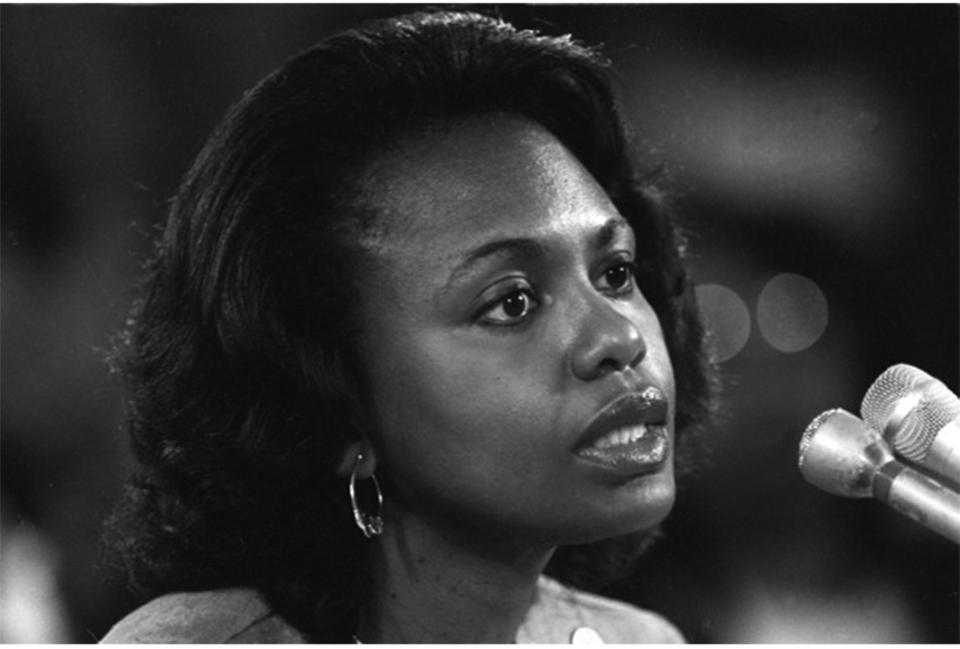

There is a moment in the footage of the 1991 Clarence Thomas Supreme Court nomination hearings when the camera pans out. Amidst a patchwork of drab business attire, one suit catches the eye—a splash of bright aqua. At this distance, it is almost possible to avoid the other, more significant differences between the blue-suited figure and the investigating panel: the person sitting alone in front of a microphone, in contrast to the majority of the Senate members, is black, and she is a woman.

In 1991, following the retirement of Associate Justice Thurgood Marshall, then-President George H.W. Bush nominated Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court. To the President, Thomas must have seemed like an ideal candidate. An African-American, he would maintain the Court’s racial composition; a proven conservative, he would likely rule in line with the president on issues such as abortion and affirmative action. Despite expected contentions with liberal factions, the hearings proceeded normally—until Anita Hill stepped forward.

II.

Hill was 35 years old, a professor at the University of Oklahoma, a graduate of Yale law school, and a former special assistant to Clarence Thomas at the U.S. Department of Education and the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission. And in the time they had worked together, Hill alleged, Clarence Thomas had sexually harassed her.

Besides repeatedly inviting her on dates and commenting on her attractiveness, Hill claimed that Thomas spoke about pornographic films, graphically told her of his sexual prowess, and commented on the size of his penis and his skill at oral sex—despite her expressed aversion to such conversation.

Hill’s allegations inspired a frenzy of controversy, from expressions of disbelief to accusations that she was vindictive or even insane. Part of this, some suggest, was due to a lack of public awareness of sexual harassment as a legitimate issue. “We had sexual harassment laws at that time, but nobody was really taking them seriously,” said Columbia Law Professor Patricia Williams in a 2011 interview with “The Takeaway.”

Yet there were other issues simmering at the time. Besides categorically denying Hill’s accusations, Thomas emphasized the potential racial dimension of the charges against him. “This is a circus,” Thomas famously said during the confirmation hearings, “It is a national disgrace ... it is a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks who in any way deign to think for themselves.”

Thomas’s words “seemed to create a racial bri[a]r patch that no white senator would want to venture into,” said New York Times Magazine reporter Andrew Goldman in a recent interview with Hill. She agreed. “The specter of racism loomed so large that he was able to get away with it,” she responded, “And it was as though my own race really didn’t matter.”

Indeed, Henry LaBarre Jayne Professor of Government and Professor of African and African American Studies Jennifer L. Hochschild explains, “Clarence Thomas was the person perceived as being black, and somehow therefore Anita Hill couldn’t be black, or couldn’t be as black.” In this sense, Hill’s identity as both a woman and an African American put many members of the American public in a bind. “Many black women said then—and maybe now—that their primary loyalty is to their race,” Hochschild says, “So they had to stick up for Clarence Thomas even if they were unhappy about doing so.”

Thomas was approved by a 52-48 Senate vote, but the Thomas-Hill controversy and the racial and gender-related tensions that it revealed were not so easily settled in the mind of the American public. “Let’s not be entirely deceived about this,” Hill commented in the same New York Times interview with Goldman. “I’m not sure that the Senate Judiciary Committee and the Senate at large were really ready to deal with gender discrimination no matter who was alleging it.” Nevertheless, Hill speculates she would have been treated differently had she been white.

Hochschild agrees. Conservatives, she comments, tended to support Thomas for his social views, but “it would’ve been harder for them to do so if [Hill] had been a white woman.” On the other hand, liberals “didn’t want to disbelieve either a black woman or a black man ... It just got very tangled up in issues of race and gender,” Hochschild said. “Nobody could quite figure out which identity took precedence.”

III.

Twenty years ago this October, a woman in a blue jacket did not prevent a man from donning black Justice’s robes. But she did spark national awareness of sexual harassment and, perhaps in a more subtle way, contributed to the discussion of what it meant to be both female and black.

Anita Hill, now a Senior Advisor to the Provost and Professor of Social Policy, Law, and Women’s Studies at Brandeis University, has been writing and lecturing on these issues since the hearings—most recently in her new book “Reimagining Equality: Stories of Gender, Race, and Finding Home.”

The Thomas-Hill controversy is often viewed as a catalyst for the recognition of sexual harassment in the United States, but it also inspired discussion on the ways in which various aspects of identity can conflict. “We have had 20 years of experience in dealing with the intersectionality of race and gender since the Clarence Thomas hearings,” Hochschild says. Twenty years in which a white woman has made significant strides towards the presidency. Twenty years in which a black man has been elected to lead the nation. Twenty years in which a Latina woman has been confirmed as a Justice on the Supreme Court. As the camera pans out over the last two decades, the conversation remains relevant.