News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

Group Refuses to Stagnate on Hyperactive Latest

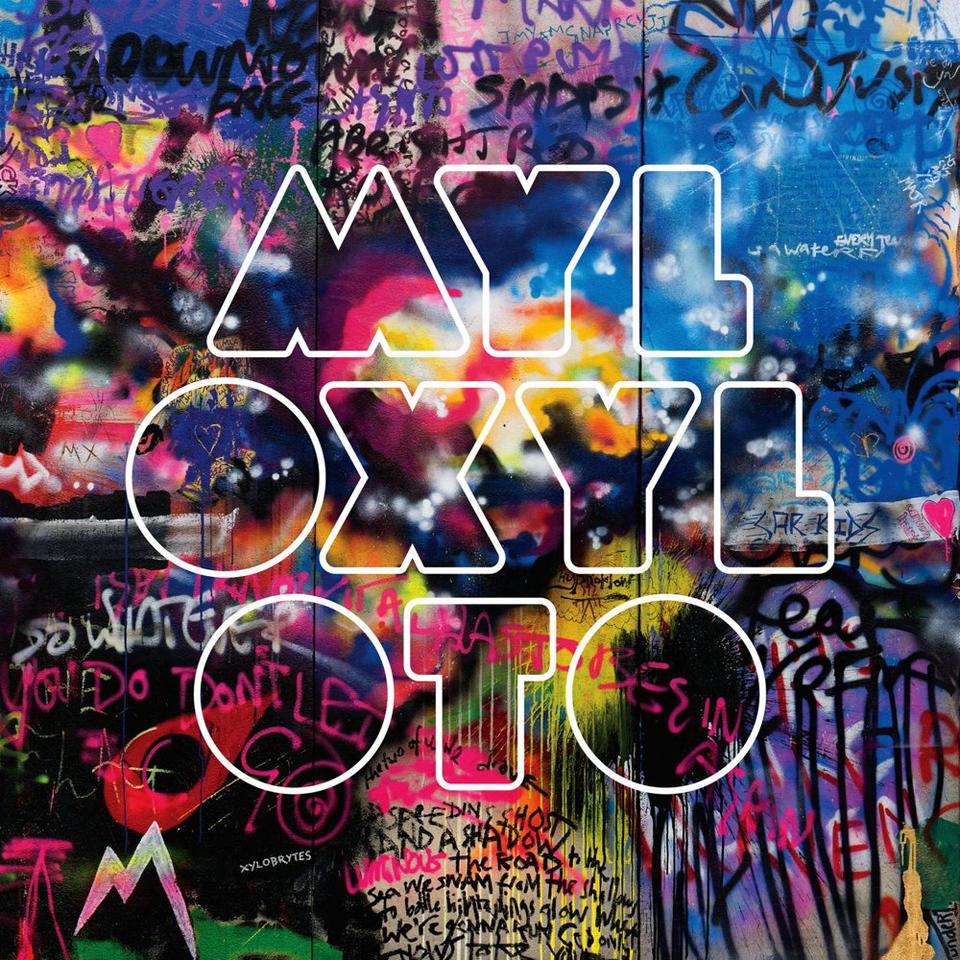

Coldplay -- 'Mylo Xyloto' -- Capitol Records -- 3.5 STARS

“Every Teardrop is a Waterfall,” the first single from Coldplay’s fifth album, is certainly an earworm. Unfortunately for Coldplay’s target audience—that is, human beings and some higher primates—“Teardrop,” unlike 2008’s “Viva la Vida,” is less like a benign earworm, and more like an earwig, or ringworm.

For better or worse, the first single is a fair indication of Coldplay’s new direction. The lyrics mean less than ever before, the synths mean more, and the melodies mean everything. But it’s Martin’s melodies that have always been the reason to listen to Coldplay; and the melodies of “Mylo Xyloto” are as big as ever.

Standout track “Charlie Brown” probably says even more than the first single does about what this album gets right, and what it gets wrong. Whereas the rest of Coldplay seems to have forgotten they once had aspirations of being a proper rock band—evidently drummer Will Champion was pawned for a drum machine halfway through the “Mylo Xyloto” sessions—at some point guitarist Jonny Buckland convinced himself that he, at least, was an honest-to-god rock star. Between the ringing wide-eyed guitar line propelling “Charlie Brown” and the distorted riff driving “Major Minus,” he makes it hard to disagree.

Buckland has quietly—well, as quietly as anyone in Coldplay does anything—developed one of the most irresistibly joyful sounds in popular music. It’s the perfect companion to Martin’s own restless ebullience, and it makes “Mylo Xyloto” what it is: a bundle of compressed, over-synthesized joy, and a surprisingly apt fit for the neon graffiti of the album’s cover. The band that began all yellow has become one of the most colorful acts in music.

Buckland makes it easy to forget that there was a time when Coldplay relied on Martin’s soft pop piano, his trademark falsetto, and a sometimes offensive excess of melodramatic conviction. But the odd thing about his emergence—and about the song “Charlie Brown” in particular—is that sometimes the surfeit of blissful melodies feels more like a cheap sugar rush than a real rush of blood to the head. It gives the impression that Coldplay’s writing process now involves coming up with an excess of good to great melodies that bear some relation to each other, insisting that each is, of course, equally world-beating, and then stringing the parts together with more enthusiasm than discrimination.

The album as a whole, though, hangs well together. The grating singles sound much better with quieter tracks sandwiching them. Between “U.F.O.”—a brief interlude that recalls the spare prettiness of “Parachutes”—and delicate ballad “Up in Flames,” even glitzy Rihanna-feature “Princess of China” becomes bearable.

As it turns out, “Mylo Xyloto,” like “Every Teardrop is a Waterfall,” means the same thing “Viva la Vida” means, the same thing Coldplay has meant since it took its first band name, “Starfish.” It means laughably absurd assertions about laughably, absurdly beautiful things. It means nothing too specific, nothing possibly offensive.

With “Mylo Xyloto” Coldplay proves itself to be the most daringly spineless band on the planet. They want nothing more or less than universal adoration, but they’ve yet to settle for recycling the same sounds that have won them adoration in the past. From the jolting start of speedball second track, “Hurts Like Heaven.” to the quiet end of the restrained, multifaceted album closer, “Up With the Birds,” “Mylo Xyloto” sounds like the efforts of a band hellbent on refusing to stagnate.

Finding something rebellious about one of the most domestic bands in rock was the trick of “Viva la Vida,” with its allusions to the French Revolution and the band’s playfully militaristic costumes: it cast simple joy as rebellion. It’s a thin line between leading a popular rebellion and struggling to be popular, but the grandiose sounds and concept-album aspirations of “Mylo Xyloto” make it hard to doubt Coldplay’s earnestness. Rihanna’s not on the album to sell records; she’s on the album because Chris Martin thinks Rihanna is brilliant. And, for what began as an indie rock band, there’s something rebellious about that.

Five albums in, it turns out first single “Yellow” told us all we needed to know about Coldplay: whom do they write songs for? You. What’s love like? The stars. And even if they haven’t quite restrained themselves to coloring inside the lines yet, Coldplay’s addition of a few more bright colors in their crayon box still feels like a victory for pop music.

—Staff writer Adam T. Horn can be reached at adamhorn@college.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.