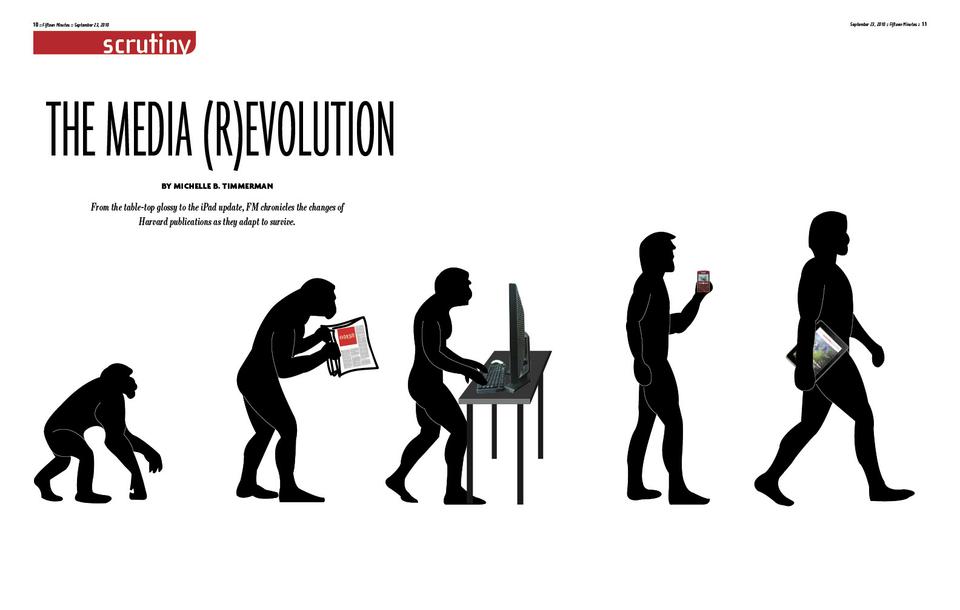

The Media (R)evolution

Harvard prides itself on being at the forefront of change, of research and experimentation, of innovation. The current cover story of the Harvard University Gazette boasts of Harvard scientists investigating the existence of life beyond Earth. A recent story from Harvard Magazine describes Francis Cabot Lowell, class of 1793, as an “American entrepreneur.”

But while these celebrated Harvard affiliates may endure well into history, the publications that recognize them—at least in the forms we know them—may not.

Like many newspapers that are trying to adapt to the shifting technological climate, The New York Times has announced its intent to make some significant changes. It will charge for online content beginning in 2011, and at a recent conference, its publisher and chairman announced, “We will stop printing The New York Times sometime in the future, date TBD.”

When the economic crisis and digital innovations press against Harvard’s gates, publications under the Harvard crown must adapt just as quickly as publications outside of it.

NEW FRONTIERS

John S. Rosenberg is an editor and media and communications specialist at Harvard Magazine, a separately incorporated magazine founded by alumni in 1898 that distributes 245,000 copies every other month to all alumni, faculty, and staff within the country.

“It’s an enormous strain. It’s not just the workload. It’s a totally different kind of deadline—the nature of the assignments, the amount of interruption, and the 24/7 nature of it. There are different rhythms, different demands...conflicts with pace from before,” says Rosenberg, of the industry’s newfound emphasis on going digital.

Consumers have had access to all of Harvard Magazine’s content online since 1996, 98 years after it published its first issue and two years before the incorporation of Google. Now, the magazine’s website receives about 100,000 visitors per month.

With this change in platform preference, so too has come a change in reporting.

“We weren’t a breaking news organization when we were publishing bi-monthly,” explains Rosenberg.

For the Harvard Gazette, breaking news is becoming standard. Once a longer, weekly magazine, in the past year it has scaled down in both size and frequency of publication.

According to Christine M. Heenan, Vice President for Public Affairs and Communications at Harvard Public Affairs and Communications, The Gazette has shifted from a print-first to a digital-first and mobile-first vehicle.

Since September 1, a new issue of the Gazette has found its way to dining halls only twice a month, reflecting a shift in the way its content is being consumed. While 24,000 issues are printed every two weeks, there are 8,000 to 20,000 page views on the Gazette’s website each day.

By those numbers, digital advance certainly seems to be the new frontier, and Harvard media outlets, packing their bags with eager innovation and financial support from the University, are heading west.

EXTRA! EXTRA!

As an alumna reads Harvard Magazine’s latest feature on HIV in sub-Saharan Africa, she is reminded by a sidebar to visit the Magazine’s website for related articles, slideshows and maps.

Similarly, nearly every page of the Gazette encourages readers to go online to find “More Student Columnists,” “More National & World Affairs,” and “More Science & Health,” among other features.

But this begs the question: do these extra features serve as supplements for the curious, or, without the optional online follow-up, is the magazine—and the reader’s comprehension of a topic—simply incomplete?

Student publications, including The Harvard Advocate, The Harvard Lampoon, and The Crimson, have begun to feature videos online as both independent features and as complements to written work.

And as video increasingly engages reader—or viewer—interest, publications are reaping the benefits.

“We joke that we wish that all of our stories had J.K. Rowling in the title,” says Rosenberg, referring to the number of page views resulting from J.K. Rowling’s 2008 Commencement Address, of which Harvard Magazine has the only full recording.

For one publication featuring content online, physical format simply became extraneous.

A bi-annual newsletter, The Yard, originated in 2005 as a publication by the Faculty of Arts and Sciences for alumni of Harvard College and the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Four years later, it went completely online in order “to generate costs savings” and “to meet the communications needs of an increasingly digital audience,” writes Ed Sevilla, Executive Director of Strategic Communications at Alumni Affairs and Development, in an e-mail to The Crimson.

“The trends in Harvard media towards digital dissemination and 24/7 information access tie directly to trends in consumer behavior and technology adoption,” writes Sevilla. “These trends

have a ripple effect upon journalism, inside and outside of Harvard.”

QUANTITY MEETS QUALITY

But even with all the extra multimedia available online, written content remains key.

“The deluge of electronic stuff, especially for us, makes the selecting, and editing and vetting even more important for people,” says Rosenberg of Harvard Magazine’s content. “If we’re coming to you in ink, it means we think it’s really important.”

However, the Gazette, for which the Internet is the primary medium of communication, sees opportunity from the decline of ink.

“In some ways the crisis in mainstream media has presented as much opportunity as it has challenge,” says Heenan, noting that the Gazette added people who formerly wrote at the Boston Globe, The Miami Herald, and The Associated Press to its team over the past year.

Yet as journalists migrate to Cambridge from prominent newspapers, news bureaus are flagging. The Wall Street Journal has closed the regional bureau that contained Cambridge, and The New York Times has cut down its Higher Education staff.

Nonetheless, the Gazette has found opportunities to become its own content channel, and to develop creative partnerships with hurting media outlets.

When President Faust met with Senator Richard J. Durbin and undocumented Harvard student Eric Balderas ’13 in Washington D.C. last week, the Gazette sent both a reporter and a photographer.

“We supplied a photograph to the Boston Globe and to The Crimson because we had the resources to do that,” says Heenan.

Editors of student magazines also serve as arbiters of worthwhile content.

“The main talent at The Advocate is not so much printing a magazine and making a good website, it’s recognizing good poetry from bad poetry,” says Benjamin S. Berman ’11, The Advocate’s Business Manager. “The content-driven imperative means the T.S. Eliots and John Ashberys won’t be writing poetry anymore. They’ll be creating interactive media only able to be published on the Internet. Our prerogative to be producing a web portal is not just how people consume web content. But the best web content will be web-based.”

CHOOSING THE RIGHT VEHICLE

As Harvard media strive to meet their consumers in the digital frontier, they must first choose and then adjust their publications to the appropriate vehicle.

“We’re interested in meeting the Harvard audience at the location where they’re increasingly gravitating to, [which is] away from the printed page,” says Heenan. “All the signs point to more and more people experiencing news and information not only digitally, but on mobile devices.”

In a five-month period beginning in November of last year, The Harvard Gazette for mobile devices received 10,000 visits. In the following five-month period, the number increased by almost 150 percent to 27,000 visits.

And next came Harvard Mobile, an application which makes information about Harvard maps, dining, directory, and news available to owners of any smartphone or feature phone device. Since its launch on September 1, Harvard Mobile has had about 3,500 downloads.

The phone features an automatic feed from stories in main categories from The Harvard Gazette.

“We draw news from the Gazette. We could see in the future drawing from other parts of Harvard,” says John Longbrake, Assistant Vice President of Communications at Harvard Public Affairs and Communications. “We’ll continue to evaluate what’s out there, what will be valuable to our audiences. You launch something, you learn from it, you refine, and you relaunch.”

Whereas the digital vehicle is essential to The Gazette, Rosenberg—of Harvard Magazine—is wary of assigning the vehicle itself too much importance.

“The actual platform is not fundamental. You have been able to get our magazine in PDF form for 10 years,” says Rosenberg, “At that time, we have had one request to not get the magazine in print.”

The Advo

cate’s Berman shares this belief in the irrelevance of the vehicle, though his critique is directed at print, not the internet. “There’s nothing special about something printed; everything is about content.”

THE HAMSTER WHEEL

Though print may or may not be special in its delivery of content, it is unique in its budgetary demands.

Most media budgets are declining in the face of the economic crisis. Indeed, the majority of those at Harvard aren’t growing either—but unlike those outside the Ivory Tower, most Harvard publications count on the University for support.

Roughly 40 percent of Harvard Magazine’s budget comes from the University; the rest is derived from alumni support and advertising sales.

The Magazine’s budget has been roughly the same for the past 15 years, says Rosenberg—in exact dollars, not adjusted for inflation.

“The reason is we’ve used technology incredibly aggressively to reduce our production costs, get better mailing costs, and to simplify our work,” explains Rosenberg.

So, the amount of work necessary to support the Magazine has grown exponentially, while the dollars and number of people involved in executing it has remained constant.

When the conversation comes to the work-staff dynamic, Elizabeth A. Gudrais ’01, a staff writer and editor at Harvard Magazine interjects.

“A magazine has a set number of pages, a set day for publication. With the Internet, you can post as often as you want. It’s infinite,” she says.

Four very industrious people produce most of the feature and breaking-news content for the bimonthly alumni magazine. Formerly, a fair amount of freelance pieces supplemented staff writers’ stories, but that has recently declined due to economic restraints.

But the staples still need to be covered, despite waiting consumers and the demand of a 24/7 news cycle.

“We’re still writing multi-thousand word features in an organized way while interrupting ourselves to write breaking news at the same time,” says Rosenberg. “We’re definitely stretching. No question. This has not been a relaxed and easy exercise. It’s a lot of work.”

The Gazette also employs the same number of reporters as it did prior to its digital shift.

So does Nieman Reports, the quarterly journal of the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard.

“We work on two different platforms,” says Melissa Ludtke, Editor of Nieman Reports. “It’s putting a bit of a strain on a small staff, and we have the same staff arrangement as 12 years ago. We work harder. Sometimes I feel like we’re on the hamster wheel. You can never stay on top of everything.”

Dean Starkman, a writer for the Columbia Journalism Review describes “the hamster wheel” in a September article as “volume without thought. It is news panic, a lack of discipline, an inability to say no. It is copy produced to meet arbitrary productivity metrics.”

The “infinity” of the Internet that Gudrais mentions, in addition to competitive pressure, can make the transition from dedicated writing to endless circling on the “Hamster Wheel” difficult to discern. Motivations and incentives can morph and weave together—the pace of print is incentivized by both the good and bad.

“We’re ambitious to serve people to do as much as we can,” says Rosenberg. “A bad reason [to keep the pace] is to be competitive. A good reason is to be ambitious. To do more and do better.”

REACHING OUT, KEEPING UP

Success at Harvard mirrors success outside of it, in that it involves learning how to sell. Sell your argument, sell your product, sell your pitch. Do everything you can, but land gracefully and deliberately short of selling your soul. Journalism is no different.

“Journalists are no longer just writing and producing their content—they’re becoming the marketers of their content,” says Ludtke. “When we finish an issue we have to do the outreach.”

The Gazette takes this to the extreme, sending out daily e-mails (opt-out for faculty and staff, opt-in for students) containing three of the top daily stories and featured events.

Forty-thousand people receive the daily Gazette. Fifteen hundred have unsubscribed. Heenan says that she targets to keep the proportion of unsubscribers at less than 10 percent.

But online interaction only begins with e-mail.

“Through development of the online Gazette, we have created a lot of the tools critical for broadening our audience—to send through Facebook, Digg, Delicious, e-mail. The ability to forward, share stories,” says Heenan. “That’s all developed in the past year and a half.”

And that’s not to mention iTunesU, Harvard Mobile, and YouTube—three other carriers of the Gazette’s content.

Harvard Magazine is equally diverse, with its mobile apps, and Facebook and Twitter pages accessible from its website.

And book-length publications, which have too been affected by technology, have also witnessed—and participated in—a dramatic shift.

According to William P. Sisler, Director and Chairman of the Board of Syndics at Harvard University Press (HUP), sales of e-books published by HUP grew from $2,000 one year ago to almost $150,000 in the fiscal year that ended June 30.

HUP maintains a Twitter and Face

book account, in addition to a new website.

“We are moving, like many other publishers, to more of a ‘pull’ kind of marketing, to engage readers in conversation with our books and authors, rather than trying to ‘push’ books out to customers,” Sisler writes in an e-mail to The Crimson.

UNIQUELY HARVARD

But as much as the round-the-clock efforts of Harvard-affiliated reporters mirror those of journalists around the globe, there’s a distinct difference between them. After all, Harvard-affiliated reporters have a built-in population of consumers that share one tangible thing in common: a Harvard degree.

“It’s one of the best audiences in the world—educated, absolutely dedicated to learning,” says Rosenberg. “Having a readership that reads and that cares and that has different opinions on things and that catches and calls you out on any mistake is wonderful. You can’t make it up.”

Meanwhile, articles at Harvard Magazine are deliberately becoming more search-friendly, that is, easier to find online.

“Years ago we did a story on how pyramids are built,” says Rosenberg, “As it turns out, every sixth grader has to do an article on pyramids. A large part of the constituency of sixth graders that have to write reports on Egypt visited our article. It comes up high on Google. We’re not writing for them, but it’s a good service.”

Harvard media—especially those targeted to alumni—are unique. For even as their general audience (including sixth graders researching early Egyptian construction methods) grows, so too does their guaranteed target audience, swelling by several thousand each spring.

Rosenberg cites University research as showing that alumni rank Harvard Magazine as their most important source of information about the University.

“It’s demonstrable that the alumni value the thing; it’s also demonstrable that although they get it free, they give us a million dollars a year. But the fact is it’s a very devoted readership,” says Rosenberg.

But not all alumni audiences have been so devoted.

In 2006, two class of 2000 College alumni created the magazine 02138.

In press releases to journalists in the weeks leading up to publication of its first issue, 02138 was described as “a new lifestyle magazine for a unique community of educated, affluent and influential readers: Harvard alumni...02138 will deliver the world to our readers from the perspective they care about most—their own.”

Not free like University-issued publications for alumni, 02138 was available through subscriptions purchased online. The magazine went quickly from “will deliver” to “did deliver,” and folded in 2008. A change in ownership and redesign prior to the collapse did little to revive the magazine. Manhattan Media, the then-owner, credited the magazine’s downfall to the “current economic environment” in a press release announcing the publication’s demise.

It wasn’t free. It wasn’t financially supported by Harvard. Its content—with features on the 100 most influential Harvard alumni and a cover featuring Rashida L. Jones ’97 wearing little but a smirk, a low-cut blazer, and a tie—differed greatly from other alumni publications. Whatever the reason, 02138 came and went in quick succession.

CHASING THE FUTURE

But it seems that most established Harvard publications, including the increasingly mobile-focused Gazette, are here to stay.

“We’ve found that in the Harvard community, particularly among faculty, there is a strong interest in print presence—people like picking up a newspaper and getting ink on their hands,” says Heenan.

Consumers change the way they consume. Digital applications change in number, scale, and popularity. Publications change in size, frequency, and scope. And indeed, no one expects the climate of contemporary change to stop changing either.

Says the Nieman Reports’ Ludtke, “I just think it through issue-to-issue and try to think innovatively and creatively.

CORRECTION: October 3, 2010

An earlier version of the Sept. 23 magazine article "The Media (R)evolution" incorrectly stated that Harvard Magazine is printed twice a month. The magazine is actually printed every other month.