The Elephant in the Room

“You’ve never been to Tenebrae, I suppose?” Cordelia asked Charles Ryder in Evelyn Waugh’s novel. “Well, if you had you’d know what the Jews felt about their temple. Quomodo sedet sola civitas...it’s a beautiful chant. You ought to go once, just to hear it.”

I had never gone to Tenebrae before I came to Harvard three years ago. It is a somber service held during the week before Easter—three hours of melancholy psalmody, chanted in a foreign tongue and, at the end when the final candle on the hearse is extinguished, enveloped in complete darkness. Reverent and sublime, indeed, but a dirge first and foremost—a lament for the present day of woe and a longing for a better time since passed.

The reverent formalities of this ancient rite no doubt seem strange to the Harvard of today. But its plaintive sentiment echoes with only too much resonance in the heart of the conservative on campus. How beautiful is this house of learning—the idyllic ivied quads, the scholarly seriousness, the august history of a three-century-old institution. But it has since been despoiled. Traditions usurped, curricula disemboweled, and the noble goal of all intellectual endeavors—the pursuit of truth—unceremoniously renounced. The Ark has been carried away and reposed in Babylon.

“Truth is an aspiration, not a possession,” I heard our president pronounce on a damp and dreary October afternoon last year. My stomach turned. Before my eyes was grand old Harvard on parade, splendidly arrayed in academic robes and bonnets, in all of its pomp and pageantry, installing its new president according to the customary prescription. Yet with a few derisive words about Harvard’s Puritan heritage from Drew Gilpin Faust and her counterpart at the University of Pennsylvania, Amy Gutmann ’71, that visible visible continuity—between the Harvard of the present and the past—was sundered.

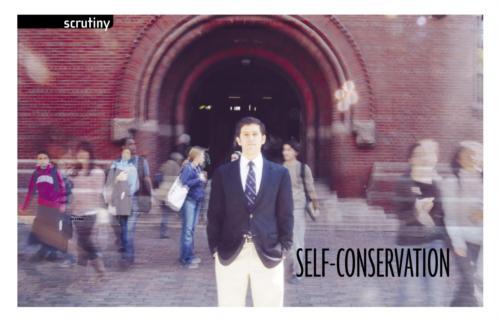

At Harvard, the conservative reflex has been to lament the despoiled temple—praise the University’s illustrious history while bewailing the perceived decline. To be a conservative means to conserve, of course, but to conserve what? This implies not only that something is worth conserving, something precious, but also something under attack, something to be defended. What at Harvard should a conservative conserve? What is a Harvard conservative?