News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

Sackler's Asian Animal House

Though winter hasn’t even officially started, signs of life outdoors are already few and far between in Cambridge. Even animals are hard to find in the Yard.

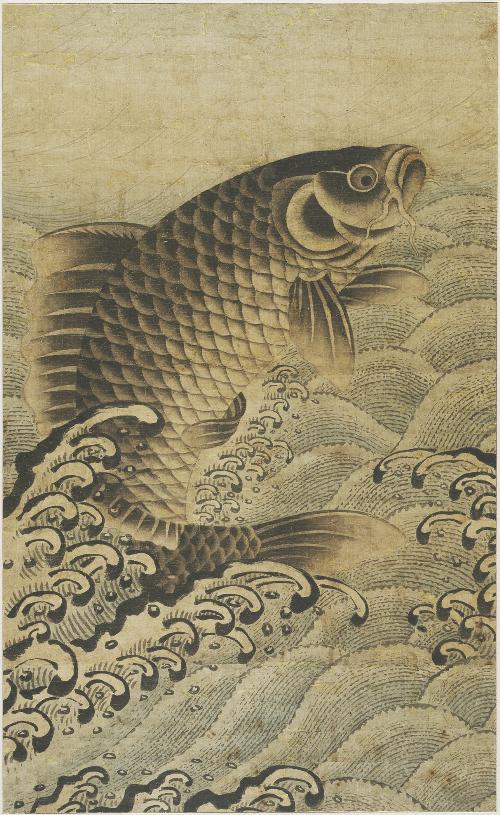

Just outside its gates, however, they’re flourishing. And these aren’t your garden variety birds or squirrels, either: they’re dragons, gibbons, and even phoenixes, all part of the Arthur M. Sackler Museum’s newest exhibition: “Evocative Creatures: Animal Motifs and Symbols in East Asian Art,” which opened on November 16, 2005. Located within the Sackler’s East Asian collection, the artwork is fascinating for any animal lover or Asian art aficionado.

Robert D. Mowry, the Alan J. Dworsky Curator of Chinese Art and Head of the Department of Asian Art at the Harvard University Art Museums, organized “Animal Motifs.”

Mowry said that “this is the first time we’ve developed the theme of animals in Asian Art.” The pieces are eclectic, including scrolls, sliding door screens, ceramic pendants, and even a bridled horse sculpture, and come from areas of East Asia—China, Japan, and Korea.

Particularly interesting is East Asian art’s predilection to focus on both real and imaginary creatures, the latter a departure from most Western artwork.

The common thread between all these works is the subject matter. The Sackler carefully considered this theme. “Animal Motifs [shows a] selection of animals with importance in East Asian tradition,” according to Mowry.

With over 200,000 pieces in the collections and storage of the Sackler, the works of art in “Animal Motifs” had to meet high criteria. Mowry says, “The museum needs collections that allow us to examine the art thoughtfully.”

There are pieces that show expressionism and others that show naturalism. The collection also represents a wide spectrum of history, ranging from the Han Dynasty (206 BC—AD 220) to the recent Qing dynasty (1644—1911). Chronologically, Mowry notes that the exhibition shows the “evolution of styles and aesthetics” within East Asian art.

Walking through the exhibition is like walking through the history of China, Japan, and Korea—albeit a history with zoological undertones.

The first eye-catching piece is a standing horse sculpture from the second century. With caramel brown glaze, the horse was an early Chinese status symbol that wealthy citizens would include in their burial tombs.

Pieces like this sculpture portray animals of the real world. But, Mowry says, that “we wanted to show there are more animals than just horses.”

Beyond these equestrian pieces are animals as diverse as the monkey, tiger, and snake. Animals of the fantasy world include the dragon and phoenix.

In “Dragon amid Clouds,” a hanging scroll from the Choson dynasty of Korea in the nineteenth century, an orange and green dragon is offset by black and white clouds. The dragon, a celebrated animal in East Asia, is chasing a wish-granting Buddhist symbol in this scroll.

“Dragons in the West are considered evil, whereas in Asia they are thought of as benevolent and even auspicious,” says Mowry.

These pieces illustrate Asian views of the dragon, also an emblem of masculinity, known in China as the “yang.” The mythical phoenix is symbolic of the feminine component of the world, or the “yin.”

A jade vase with nephrite yellow and brown markings—a wine vessel from the early eighteenth century—portrays the yin and yang relationship, with images of the dragon and phoenix on opposite sides.

In another handscroll, from the seventeenth century, “The Twelve Zodiac Animals as Poets,” animals are used to reflect cultural symbols. Animals from the traditional Chinese zodiac are satirically dressed in elaborate garments like the stoic Asian poet.

The poetry of these famous poets was entered into competitions at the imperial court; simultaneously portraits were erected to depict the authors in tandem with their writings.

In this particular scroll, animals like the snake and tiger, with their smug expressions, extravagant robes, and blinding bling, are skewing the pictorial legacy of the Asian poet.

With “Zodiac” animals are not depicted as fearful or inhumane, often the case with Western depictions, but playful. This same nature is epitomized in the working of a two-panel folding screen known as “Gibbons Playing in an Old Tree along the Bank of a Stream.”

This screen door is both practical as a household appliance and artistic, with monkey-like creatures configured with naturalistic brushes. Its premise is that a number of the animals are linking arms under a tree branch hoping to reach for the moon, but only moving closer to the moon’s reflection in the stream. It’s a subtle reference to Buddhist philosophy but also, more importantly, a powerful statement on illusion and reality—and perhaps art itself.

And though the Sackler’s exhibit is in essence a reflection of a reflection—a Western perspective on an Asian perspective on animal life—it shares the positive connotations of the painting. “Evocative Creatures” gives viewers a window into the foreign world of centuries-old East Asia, a world perhaps as mysterious and faraway to many Cantabrigians as the painting’s moon is to its gibbons.

“Animal Motifs” runs until June 12.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.