News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

Divinity, Faith, and Loss in Lewis Bio

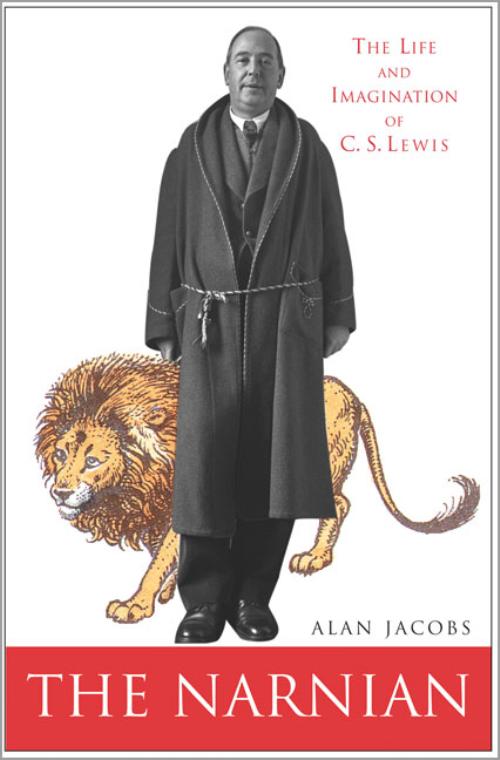

The Narnian by Alan Jacobs

While five-year-olds and fantasy fanatics gear up for the new film adaptation of “The Lion The Witch and The Wardrobe,” Alan Jacobs struggles to reveal the man behind the fairy tale in “The Narnian.” The book—part biography of C.S. Lewis and part literary critique of his works—provides greater insight into Lewis’ continuing influence on thinkers like Jacobs than it does into Lewis himself.

“The Narnian” portrays Lewis as a man defined by his imagination and his inward life.

Jacobs seeks to understand the mind behind the stories rather than the biographical minutiae of Lewis’ outward life, relying often on letters and close readings of Lewis’ texts. He names “[his] belief that Lewis’ mind was above all characterized by a willingness to be enchanted” as the cornerstone of his analysis.

Yet Jacobs is an apologist as well as an investigator—his unflagging admiration for Lewis shines through even his critiques.

While writing the book, Jacobs had access to what he terms “the finest collection of Lewis research materials in the world,” a collection of Lewis’ letters and writings. The collection is part of Wheaton College’s holdings, a school which lists “the development of whole and effective Christians” in its mission statement and where Jacobs is an English professor.

More interesting, however, is Jacobs’ apparent appropriation of Lewis’ own style. He emulates Lewis’ distinctive voice, adopting a conversational tone and using italics liberally. Yet Jacobs rarely succeeds in his desired effect—his parenthetical comments are more often off-putting than endearing and his clumsy prose is a poor match for Lewis’ fluency.

Lewis’ fascination with the fantastic began at an early age, when he formed an elaborate mythology with his older brother in the upper room of their house in Ulster. Stories sustained Lewis through a difficult childhood, beginning with the loss of his mother and continuing in a series of nightmarish episodes at boarding school.

Exceptionally gifted at his scholarly pursuits, Lewis nonetheless suffered from social awkwardness in his youth. He prized solitude and became a “thoroughly obnoxious, arrogant, condescending intellectual prig,” as he put it, by his teens.

A stint fighting in the trenches of World War I resulted in a fairly unsuccessful book of lyric poetry which nonetheless demonstrated Lewis’ considerable talents. Lewis also began an affair with the divorced mother of a friend who died in the war. The relationship would last until the end of her life, decades later.

After the war, Lewis went to Oxford and stayed there for nearly the rest of his life.

In time, Lewis became the large, loud, Medievalist who laughed deeply and held late-night meetings for friends and intellectuals. He developed close companionships with fellow academics, most notably J.R.R. Tolkien.

On a walk one evening with Tolkien and another friend, Tolkien convinced Lewis that his lifelong yearning for a feeling which he called Joy was, in fact, a longing for God. The friends debated until sunrise, when the middle-aged Lewis became a Christian.

Lewis’ conversion from atheism to Christianity influenced the rest of his works and resulted in a series of Christian apologetics.

The popular success of books like “The Screwtape Letters” and Lewis’ talents in oratory and debate contributed to his status as spokesman for many Christians, both then and now.

Jacobs reveals himself to be a devotee of Lewis’ religious works, writing “It was probably not likely that such an open mind would remain atheist long.” He intimates that Lewis’ love of myth was only fully realized in his belief in the Christian narrative.

Yet Jacobs also takes pains to point out that to many readers, Lewis is simply the man who conjured the Chronicles of Narnia. Jacobs narrative of Lewis’ life strays at times to Lewis’ beliefs or the literary climate of his time, but it always returns to Narnia.

Lewis wrote that it was only when the character Aslan “came bounding in” to “The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe” that the story and subsequent series began to make sense. The self-sacrificing lion is the ultimate ruler of Narnia who returns to rescue it from the oppression of the White Witch.

Aslan is Narnia’s savior.

Jacobs appears to attribute a similar, if not quite as extensive, power to Lewis himself. His description of Lewis as larger-than-life, deeply kind and perennially jovial strays eerily close to reverence. It is Lewis, bounding into the lives of his readers, who teaches them to imagine and to truly feel delight. If Jacobs doesn’t want to deify Lewis, he certainly wishes to canonize him.

Chronicling the richness Lewis found in his whimsical visions, Jacobs demonstrates that Narnia is as relevant for today’s readers as it was for children in post-World War II Britain.

While dogged by stylistic mediocrity and overwhelming bias, “The Narnian” demonstrates the power of Lewis’ imagination to both sustain and inspire. Jacobs’ point (and Lewis’) is that the power, ultimately, is in the story itself.

—Staff writer Allison A. Frost can be reached at afrost@fas.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.