News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

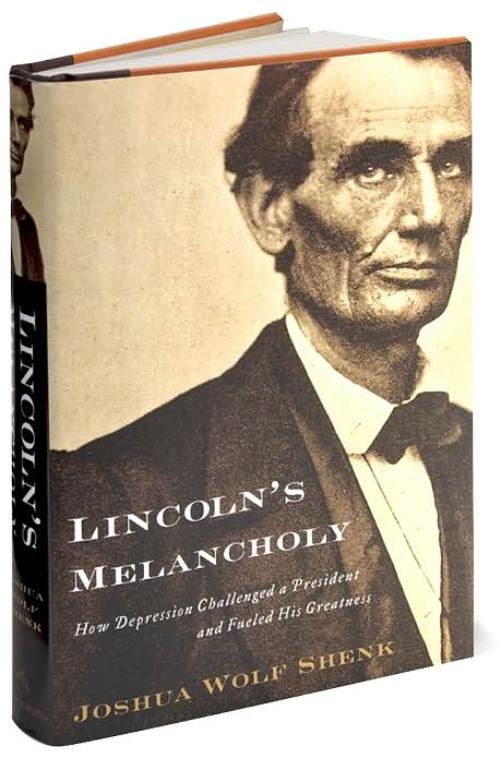

Was Abe’s Depression a Boon?

"Lincoln's Melancholy" by Joshua Wolf Shenk '93

The next time you handle a $5 bill, take a look at Abraham Lincoln’s

face. His expression suggests a gloomy disposition, even depression—an

illness that today might be a political liability.

That image of Lincoln is historically accurate, according to

Joshua Wolf Shenk ’93, author of the new book “Lincoln’s Melancholy.”

But Shenk argues that, instead of being a tragic flaw, the Great

Emancipator’s depression was a key source of his success.

Shenk, also a Crimson editor, got this idea seven years ago

when he saw a reference to Lincoln’s melancholy in a sociologist’s

essay about suicide.

Although Lincoln’s “melancholy” was well known among his contemporaries, it has been largely ignored by historians.

“There’s never been a book to focus on Lincoln’s melancholy and

to gather together all of the material related to the melancholy and

make sense of it,” Shenk says in a phone interview.

Shenk took both a professional and personal interest in the

topic of mental illness. “I was used to studying politics and culture

and history and was also really depressed myself,” he says, adding that

since his late teens he has struggled to manage depression. “I thought

that I could chart a course for my own self by studying the subject in

my professional work.”

Shenk’s personal experience with depression gives his version

of Lincoln an underlying sympathy and sensitivity toward Lincoln’s

forlorn thinking. But Shenk says that he has no personal agenda with

this book other than to present a new view of Lincoln.

“I haven’t been using Lincoln to understand myself,” he says.

“I’ve learned many things that are helpful to me, but they’ve all come

from setting myself aside and looking at Lincoln on his own terms.”

Shenk’s ability to weave a compelling narrative is indeed the

book’s greatest strength. He offers a sort of “E! True Hollywood Story”

behind nearly every major event so famously associated with Lincoln.

The character of Lincoln in Shenk’s book is one who deprecated

himself after his hugely successful speech to financial leaders at

Cooper Union’s Great Hall in New York in 1860, who wrote dismal verses

about death and suicide, who emanated sorrow that at once frightened

and attracted people near him.

However, this is also a man who translated his “depressive

realism,” a term Shenk quotes from psychological literature, into a

passion for finding and accomplishing a greater purpose while

weathering life’s tribulations.

Like this version of the book’s hero, Shenk is humble,

recognizing his own limits as a historian. Referring to some

historians’ claims that Lincoln was homosexual, Shenk doesn’t rule out

such a possibility, but writes that “with people in history, our

understanding is limited by available texts. Intuition and common sense

can help, but only if they’re leavened by an awareness that the world

we see ‘onstage’ is different from the world we live in.” The fact that

Lincoln and companion Joshua Speed were bedmates was not unusual in the

nineteenth century, and “a frank avowal of our ignorance is the first

step in honestly dealing with Lincoln’s sexuality,” Shenk writes.

When he writes of Lincoln’s views on slavery, Shenk is just

as sensitive to Lincoln’s cultural environment. Shenk acknowledges that

Lincoln was in no way fighting in favor of equal rights for

African-Americans—only for the abolition of slavery as an institution.

But despite the focus on Lincoln’s depression, particularly

in the discussion of his life before the presidency, Shenk’s book

becomes more about Lincoln’s admirable character traits than his mental

illness. Shenk’s eloquent explications of Lincoln’s speeches—as well as

anecdotes of Lincoln’s kindness and good sense of humor—become more

intriguing than the book’s argument that his great asset was his

melancholy.

Perhaps this is because Lincoln tempered his depressive

episodes as a public figure and older man. But the reader is left with

the impression that many qualities separate from Lincoln’s

depression—including his persistence and his famous lack of malice

toward the South—contributed more to his greatness.

Ultimately, Shenk just wrote another book about the Lincoln

legend. To his credit, Shenk does bring modern psychological knowledge

to bear on our understanding of the sixteenth president.

And his book adds another nuance to our romanticized portrait

of the Illinois Rail-Splitter. But the argument that Lincoln’s mental

condition was central to his greatness loses steam.

That said, Shenk believes that Lincoln’s depression cannot be

separated from his personality, and that the modern tendency to see

depression as distinctly separate from ordinary mental states isn’t

accurate.

“My sense is that Lincoln came to understand that he had a

condition that was somehow organically connected to his

constitution—something he was born with that was not going away,” says

Shenk.

Lincoln’s contemporaries, Shenk says, saw melancholy as a

temperamental style, as part of someone’s character. Those afflicted by

melancholy might have been more prone to nervous states or debilitating

disease. But melancholy was part of a spectrum.

Shenk says that even if readers see Lincoln’s contemporaries’

views on mental illness as inferior to modern psychology, “it makes you

think that these things are in flux, that our relationship to

depression is a relationship of ideas. We’re developing and thinking

about these things, and they can shift over time.”

And so, too, is our view of Lincoln ever-evolving.

—Staff writer Katherine M. Gray can be reached at kmgray@fas.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.