News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

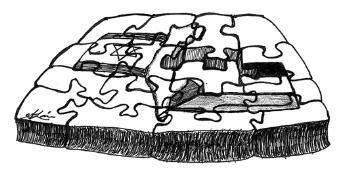

The Missing Piece of the Puzzle

Following the last round of Israeli-Palestinian permanent status negotiations at Taba, Egypt in Jan. 2001, there was a strong sense, shared by most of the participating negotiators, that the parties were in substantive terms very close to reaching an understanding on all issues. Both sides had accepted in principle the guidelines on final status that President Clinton had presented to them a month earlier. But there was no deal, and the parties agreed to resume negotiations after the Israeli elections of 2001 and Ariel Sharon’s victory.

Some of the negotiators from both sides, acting in an unofficial capacity, decided that there would be great importance in informally continuing and completing the work of Taba. The point of departure was the lessons learned from the negotiating experience under former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak from November 1999 to January 2001 and the need to integrate and develop these lessons. Initially, the exercise focused on producing a detailed blueprint for an agreement on all issues, based on the conclusion that “constructive ambiguity” in relation to these issues had become damaging to the peace process. The end product—a detailed and final agreement—would become the reference point for peace and could be used by future negotiators or other interested parties.

As the situation on the ground deteriorated, undermining the confidence of both the Israeli and Palestinian communities, it became clear to many that some action had to be taken. And so, in the spring of 2002, the protagonists in this exercise, including several current and former officials in the Israeli government and the Palestinian Authority, decided to work on a draft paper that would serve as a model for the end game in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. They would produce in Switzerland a detailed agreement of about 60 pages, with detailed attached maps, that would give clear and specific solutions on all issues. I participated actively in the initiation of this process and in numerous negotiations in the United Kingdom, France and Switzerland, first as an individual and, since April 2003, as special representative of the Swiss government for the Middle East peace process. I was also asked by the parties to help them broaden the circle of the potential signatories.

The broad outline of the agreement was finalized at a decisive meeting organized in Oct. 2003 and presented to the public in Geneva on Dec. 1. Meant to compliment the road map that was presented in May 2003 by the quartet of the U.S., the U.N., the European Union and the Russian Federation, the Geneva agreement is in fact the missing piece of the puzzle. As is well known, the road map envisages three steps with clear objectives and deadlines: first, the Palestinians immediately undertake measures for the cessation of violence and reform their institutions, while Israel dismantles settlement outposts erected since 2001. In the second phase, a Palestinian state is created with provisional borders and attributes of sovereignty. Only then, in the third and final phase, do the parties negotiate the final status of the Palestinian state.

The road map formulates a necessary process. If the Palestinian terrorist attacks and the spreading of the Israeli settlements do not end, a final and negotiated agreement is inconceivable. Moreover, the road map is an official document accepted in principle by the Israeli government and the Palestinian Authority. However, it envisages a peace process based on conditionality and sequentialism, and it is these elements that render the process fragile. Each interim commitment becomes the focal point for the next dispute and a microcosm for the overall conflict, leading to endless accusations. Lacking a clear vision of where they are heading, both sides treat the different phases as an opportunity to optimize their bargaining positions. How, then, can the Palestinians be asked to participate in an endeavor whose final destination is totally unknown? How can the Israelis be asked to compromise on security issues without knowing the nature of the state next to which they are supposed to live?

Here is where the Geneva agreement complements the road map. It represents a model for the road map’s third phase at the outset by resolving four crucial problems unsolved in previous negotiations. First, the agreement settles the borders of the non-militarized Palestinian state: Israel would withdraw to its 1967 borders, dismantling the major part of the Jewish settlements. Where dismantlement is no longer possible, the resulting loss of Palestinian land would be compensated by “one to one” land swap. Second, the agreement deals with the question of Jerusalem, dividing it into western and eastern parts, which would become the capitals of Israel and Palestine respectively. The Old City would remain undivided and open, but the different quarters would be attributed to either Israel or Palestine according to the majority of the quarter’s population, as in the Clinton parameters. The Temple Mount/Haram Al Sharif would be under Palestinian sovereignty, the Wailing Wall under that of Israel. Third, the Palestinians would renounce their right of return, meaning that Palestinian refugees could only take residence in the new state of Palestine (including the swapped territories), emigrate to a third country or remain in their current host country. Immigration to Israel would only be possible in the limited framework of a family reunification program, the implementation of which would be at Israel’s sovereign discretion. Fourth, a U.S.-led multinational force would be created to guarantee both parties’ security and to supervise the provisions of the agreement.

It is likely that a definitive and comprehensive resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict will be based on the Geneva agreement, since it represents the maximum acceptable to the Israelis and the minimum tolerable to the Palestinians. The basic elements of the agreement already command majority support among both Israelis and Palestinians, as shown in a poll released on Nov. 24 and commissioned jointly by the James A. Baker III Institute at Rice University and the International Crisis Group.

To a certain extent, the road map is a puzzle. The pieces are on the table, they are numbered and we only have to follow the instructions laid out in the document. All seems simple and clear, yet one crucial piece is missing without which we cannot complete the puzzle. The Geneva agreement is the missing piece of the puzzle. It is a model for a permanent status agreement that will allow the road map to proceed and finally implement the two-state solution.

Alexis Keller, a former associate professor of political science at Geneva University, is the special representative of the Swiss government for the Middle East peace process. He will be a fellow of the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at the Kennedy School of Government beginning Feb. 15.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.