News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

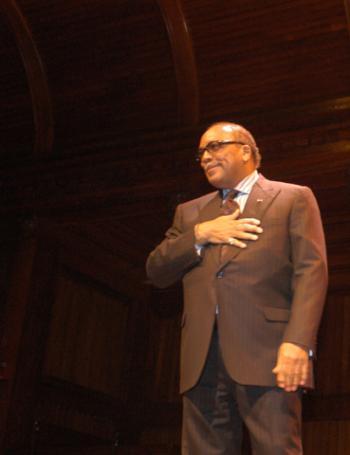

American Icon

Living legend Quincy Jones spoke to the Harvard community on his life and contributions to the American music landscape.

Quincy Jones’ numbers boggle the mind. He has scored 34 movies and produced or played on 221 albums, including 57 solo projects. He produced the number-one selling album of all time, Thriller, and has 76 Grammy nominations—the most ever for a single artist—with 26 wins. He was nominated for the Oscars seven times, the Golden Globes thrice and the Emmy Award four times, with one win.

But the list continues. Jones has received the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award, along with an astonishing 23 other humanitarian awards. He’s received everything from the key to the city of Indianapolis, Indiana to that of Paris, France.

No numbers, however, can describe the power and presence of this living legend when he speaks in the flesh. Fortunately, many students at Harvard had this extraordinary opportunity last week, when the Office for the Arts (OFA) brought Jones to campus as the newest participant of the Kayden Visiting Artist Program. Jones’ connection to Harvard is extensive—he received an honorary degree from Harvard in 1997, the same year his daughter, Rashida, graduated from the College. Jones also persuaded AOL Time Warner to endow the Quincy Jones Professor of African-American Music chair in Harvard’s African and African American studies department. Ingrid Monson, the professor of the popular Core course Literature and Arts B-82, Sayin’ Something: Jazz as Sound, Sensibility, and Social Dialogue, currently occupies the seat.

Jones was at Harvard for three nights last week, and he spent his time shuttling between a meeting with campus musicians, having lunch with members of the Harvard arts community and discussing his movies at the Brattle Theater with Assistant Professor of Visual and Environmental Studies and of English and American Literature and Language J.D. Connor ’92, who is also a Crimson editor. The finale came last Thursday night—an extended talk with W.E.B. Du Bois Professor of the Humanities Henry Louis Gates, Jr. at Sanders Theatre.

The sold-out event at Sanders was a hot ticket among students and local fans, who clamored to see the living legend speak.

“At first, when I heard he was coming I thought I wouldn’t be able to get tickets, ’cause, I mean, he’s a legend. I think between me and my family, [we] have most or all of his albums,” said Dominique C. Deleon ’04, who was able to secure a coveted ticket to the event. “Part of what makes him a legend is his ability to relate to so many different types of people.”

At every event Gates’ seemingly effusive declaration that Jones’ “powers of persuasion are legendary and considerable” is quickly revealed to be an understatement.

Jones’ persuasive powers derive from his charisma and the history that his impressive list of accomplishments brings. As Oprah put it in a clip from a documentary shown at the Sanders Theatre event, “Quincy Jones on a bad day does more than most people do in a lifetime.”

Jones’ rhetorical style is in refreshing contrast to the seemingly canned speeches politicians rehash so often. Watching Jones respond to the questions of fans and interviewers gives the impression that he answers exactly as he believes. Jones’ unique personality gives his comments, which might otherwise get dismissed as clichéd platitudes, the ring of truth.

When asked about Kazaa and other file-sharing programs, he responded simply that, “You have to figure out what’s fair.” Though an obvious oversimplification of the controversy, Jones’ response made it seem reasonable to reconsider the possibility that there is an attainable, fair and final agreement.

In another session, Jones said of the file-sharing services that, “I’ve been in the business 53 years, and I’ve never seen anything like this; but it’s God trying to tell us something.” The key, he said, is that, “nothing lasts, you have to keep going.” A large part of Jones’ success, he realizes, is that “I’ve been open to change.”

Jones implicitly contrasted himself with other artists and businessmen in the music industry. He said, “You can know anyone’s age, creatively I mean, by observing the degree of pain they exhibit when shown something new.” Jones, on the other hand, knows that when new technologies appear, “You have to understand it so you can use it, and it doesn’t use you.”

Examples of Jones’ simple but wise philosophy were evident throughout his talk. He said he decided to understand the business side of the music industry because, “you figure out what you have to do. I saw Basie and Duke pay a lot of dues. At some point you say, I don’t want to be controlled by those considerations.”

Much of Jones’ speech was also quite spiritual. When asked if he is still impressed meeting famous or important people after leading such an impressive life, Jones responded that, “I get impressed with the humanity of a person.”

Jones reiterated the theme of integrity, particularly with regard to questions about the Hip-Hop world. He feels that all artists “are just vehicles for God to come through, and when you only talk about the Benjamins, God will not be on your side.” He had a similar answer to people looking for keys to their own artistic growth. “As Coltrane said, ‘It’s all out there.’ You just have to have the divinity to be able to claim it,” Jones said.

Jones added that “Rappers are the most creative people I’ve worked with since Beboppers.” His history of working and conversing with everyone from Queen Latifah to Chingy to Dr. Dre gave his praise greater weight.

Comparison with Bebop is also one of the highest compliments Jones can give to any genre—as he made his musical bones under the shadow of Beboppers and has a reverence bordering on the religious for icons like Miles Davis and John Coltrane.

Perhaps because of Jones’ strong appreciation for the talent of contemporary rappers, he vehemently denies the rumors of Hip-Hop’s impending and inevitable demise. After one particularly declaratory comment, Jones responded, “Hip-Hop is dead? That’s what Michael [Jackson] told me in 1987. It’s not true, you just have to change. I’ve seen 60 years of groups go by and it’s all adding up to something more.”

THE MAKING OF AMERICAN MUSIC

Quincy Jones is able to persuasively chart the flow of 20th century music, as his talent and strong personality has kept him on top. Talking about the theme to Sanford and Son, a TV show starring his old friend Red Foxx, Jones says that, “I wrote that as a musical impression of Red Fox’s personality.” The statement is accurate and astute, and his work often exhibits a psychological perceptiveness and depth.

Jones’ modesty and talent was particularly evident when he discussed the process of producing other musicians. He said, “It’s pretty easy, because they have their dynamics already laid out, and you just have to know the artist well; it’s all about love.”

At the Brattle Theatre talk, many of the audience’s questions also focused on Jones’ legendary career in film scoring, which broke down the boundaries against African-American composers. “I’ve wanted to do films since I was 15,” he said. The great thing about scoring, Jones insisted, is that, “you can let your imagination run wild.”

Jones also noted a danger of the film business. In his experience, “as a musician you get stereotyped pretty quick.” As soon as “you do hits all the colors fade away” and you become typecast as only being able to create one genre of film score. Sensing this early, he constantly reiterated, motivated his constant drive “to keep moving. Once they say, ‘oh, yeah, Quincy, he does thrillers real good,’ I go do some comedies.”

Jones’ ability to inventively vary his technique without compromising quality quickly vaulted him to the top of the world of Hollywood composers. “When scoring, you can either use representative music or you can have a chasm between what’s on screen and the music. I think it’s more interesting to do both,” he said. He also knows that “in order to write a good score you have to stay away from the dialogue.”

Appreciation of Jones’ ability spread so quickly that by 1967, only four years after he began to score American features, acclaimed director Richard Brooks got him to score In Cold Blood even before he cast the movie. Brooks got an even better than usual performance from Jones, which he readily admitted: “When a director calls you before the actors, you give it 10 times the effort.”

Today, In Cold Blood is clearly dated and tainted by the irony of Robert Blake playing a cold-hearted killer, but Jones’ music holds up. It is clear what Jones meant when he said that “music paints the psyche of a film; it gives it a pace, a contour.”

The music allows the movie to move as though the audience already knows the characters, because the personalities of both the villains and victims are clearly introduced. These people’s history come to life because of the imagery and personality the score invokes.

Near the end of his interview, ‘Skip’ Gates broached the topic of Michael Jackson, who owes much of his solo career success to Jones’ producing talents. As Gates put it, “What happened to that cute little colored boy?”

Jones replied that Michael’s problems is that he “grew from a poor black child into an old white woman.” He moved on to giving his implicit and more damaging criticism, that, “You have to approach your alter of creativity with humility and grace. You have to live your life from the inside-out and not the outside-in.” He went on to name Oprah and Will Smith as celebrities who have managed to keep their good nature and integrity in the face of fame.

The night’s other highlight came when the audience got a chance to see Jones listening to his own music in the theatre. Jones closed his eyes, and began to shake his foot to the beat, with his pleasure in the music rising in him. He then looked up to see his mostly middle-aged and seated audience’s intense enjoyment of the same music, evident by the universal clapping to Jackson’s “Billie Jean.”

His was the relief a true artist can feel when he knows his art is safely enshrined by posterity.

—Staff writer Scoop A. Wasserstein can be reached at wasserst@fas.harvard.edu

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.