News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

The Gospel of West

Harvard’s most famous expat returns to Cambridge to discuss aggressive militarism, Summers and how to reform democracy

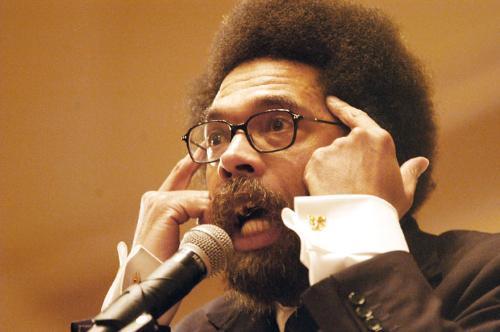

It is fitting that when Cornel R. West ’74 came to Harvard last Saturday to discuss his new book, Democracy Matters: Winning the Fight Against Imperialism, he spoke not in the halls of Sever or Emerson, but at the pulpit of First Parish Church.

When you see him in his finely tailored all black three-piece suit, thrusting his arm and clenched fist out at the packed crowd in a sign of Black Power, his voice wavering like an erratic EKG printout, reaching a crescendo mid-sentence and then trailing off so that he whispers the last word, syllable by syllable—“hu-man-i-ty”—it is then that you realize that Cornel West is not your ordinary professor.

This Princeton University Professor of Religion is a preacher, and his congregation today realizes that. They chime in to his words with the occasional “that’s right!” or “tell ‘em!” that you would expect more of a Sunday afternoon homily than a Saturday night book discussion sponsored by the Harvard Book Store.

West’s gospel today is of the secular sort. He preaches that democracy is “in crisis” and that “we need to be reminded of the intellectual and political resources available in the democratic tradition that we can build on in order to deal” with those threats.

He blends together old-school academia and new-school pop culture, invoking Socrates, Herman Melville and Snoop Dogg to advocate critical examination first of one self, and eventually of one’s government.

“Let’s engage in Socratic questions for a certain intellectual integrity and moral consistency,” he sermonizes. “It’s a matter of deciding ‘Is this the person I want to be?’” He ends the sentence with what, only five minutes into the speech, has become his trademark: he draws out the last syllables of the sentence, making his plea seem even more urgent.

We must follow Socrates’ exhortation in Plato’s Apology that “the unexamined life is not worth living,” he says, because only through self-examination can we recognize in what ways we need to improve our democratic society. An examination of the problems with our democratic society, and an argument for how to overcome them, constitutes the bulk of Democracy Matters.

But along the way West, ever the controversial figure, especially since his bitter public dispute in 2002 with University President Lawrence H. Summers resulted in West’s departure from Harvard for Princeton, manages to ruffle a few feathers along the way, as he talks about the “niggerization of America,” the “evangelical nihilistic arrogance of the Bush administration,” and even devotes a full 11 pages to retelling his side of the Summers affair.

WHY DEMOCRACY MATTERS

West outlines the threats to democracy as free market fundamentalism, aggressive militarism, and the dogma of increasing authoritarianism. Free market fundamentalism he defines as “fetishizing unregulated markets,” which provides an excuse to rationalize rising wealth inequalities. Under the heading of “aggressive militarism” he includes everything from America’s invasion of Iraq to domestic violence. And by the “dogma of increasing authoritarianism” he means a mindset that has allowed the United States to, according to West, violate the rights of prisoners of war captured abroad in Iraq and Afghanistan and to racially profile Arab-Americans at home.

West invokes Melville in a call for Americans to critically question what he views as the hijacking of democracy by anti-democratic and oppressive forces.

“If you’re well adapted to a status quo that is oppressive, something is wrong,” he pleads from behind the pulpit.

He argues that material success and personal power have become the highest values in American culture today, above even liberty. Americans have begun to define themselves in terms of these materialistic values, and this has harmed society by deflating it of more altruistic values. America, to West, has succumbed to nihilism.

It is his hatred of nihilism that drives the book and leads to his call for Socratic self-examination. Indeed, in an interview after the speech he defines nihilism as “a gangster way of life. It is amoral, it is obsessed with might and force. It’s both a mindset and a mode of behavior. It’s unprincipled and it’s dangerous.”

West takes particular issue with the Bush administration specifically—hence the “evangelical nihilistic arrogance” charge—and with America’s prosecution of the war on terror more generally. He uses the term “niggerization of America” to describe a country that in the wake of September 11, 2001 shares the black experience of being widely hated by others. West says America has responded to international terror with a hatred that blacks have historically not employed when struggling against American terror and hate directed against them.

“If Martin Luther King responded to American terrorism the way we [America] respond to foreign terrorism, we’d have a civil war every generation,” he says.

West’s solutions are three-fold, yet also largely theoretical. He urges America to affirm “the Socratic commitment to questioning,” a “prophetic commitment to justice,” and a belief in “tragicomic hope.”

From behind the pulpit, he emphasizes the Socratic questioning most of all, urging his congregation to ask “What does it mean to be human?”

West believes that such questioning will empower humans to overcome the oppressive status quo they see in society. He says that blacks have historically been forced to do this in the face of continual oppression, but that today all Americans have succumbed to an insidious nihilism that has allowed them to become permissive of tyranny and oppression in their midst.

And citizens must use their power within a democracy to bring about the necessary changes to the system.

“Democracy is always a movement of an energized public to make elites responsible,” he writes in Democracy Matters. “Democracy is not a system of governance, as we tend to think of it, but a cultural way of being.”

But West’s solutions have become a source of criticism of his book—while he is able to point out concrete ways in which democracy is ostensibly crumbling, his solutions remain largely theoretical and ill-defined. Essentially, encouraging Americans to engage in Socratic dialogue with their inner self—to have them ask “what it means to be human”—is easier said than done.

Caleb Crain, reviewing in the book in the New York Times, writes, “Unfortunately, whining about the hyenas [that assault democracy] is, for the most part, what occupies West in Democracy Matters. I agree with his sense that ‘we have reached a rare fork in the road in American history.’ But I am not sure this book will be much help.”

The book has also struggled elsewhere in the New York Times—on its bestseller list. It debuted at #11 on the October 10, 2004 listing, but has since dropped every week and is no longer among the top 35 sellers.

But reception of the book has not been completely negative. Tony Norman, reviewing the book in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, praised West for his famous eloquence.

“His work displays a clarity of language that Race Matters, for all of its ground-breaking insight, lacked,” Norman writes, referring to West’s 1993 bestseller that has sold more than 400,000 copies. “West is still capable of getting tangled in sentences of unnecessary complexity, but he does a better job making his points without resorting to distracting jargon.”

Yet Crain criticizes West’s writing style for what he sees as its “eccentricities of tone.” In particular, West is very ready to lavish praise on friends—he lauds the Wachowski brothers, who cast him as “Counselor West” in The Matrix sequels for their “deep democratic vision” and Tavis Smiley, on whose National Public Radio West is a habitual guest, as “the most influential democratic intellectual in mass media of the younger generation—and possibly of any generation.”

And he does this while reserving his harshest words for enemies—most prominently, Harvard President Summers.

JUST LIKE OLD TIMES

Norman writes that “even [West] isn’t above settling old scores as he lays out a blueprint for a more progressive politics of engagement,” and the 11 pages that rehash West’s version of his notorious spat with Summers bear this out as fact.

West never directly mentions his ugly break with his alma mater during his Saturday evening book discussion, but he does not completely ignore what for Harvard faculty and students is the elephant in the room.

“I am blessed to be back in Cambridge” to engage in critical and open discussion, West says, because “that is what Harvard is about—at it’s best.” As the crowd laughs, he repeats “at it’s best” once more to drive the point home.

But Democracy Matters is not one for glancing blows.

West goes into great detail recounting how, soon after Summers took over as University President in Oct. 2001, he requested a meeting with West in which he allegedly criticized the then-University Professor’s academic integrity and told him to make better use of his time than making a rap CD and working on Bill Bradley’s 2000 Presidential campaign. Summers also allegedly criticized West for allowing grade inflation in his class which, the New York Times would later report, gave A or A- grades to 50% of students.

West minces few words when using his book to respond to Summers’ charges. He repeats past charges that the president is “a bull in a china shop…an arrogant man, an ineffective leader,” adding that his “vision puts a premium on accumulating academic trophies and generating sizable income in the form of government contracts, foundation grants, and business partnerships” on an insular campus that does not reach out to the larger democratic society.

He also accuses Summers of trying to conspire with West in “bringing Professor Mansfield down,” referring to Kenan Professor of Government Harvey C. Mansfield ’53, though he does not elaborate further.

West, who elsewhere in the book criticizes “aggressive militarism” as one of three major threats to contemporary democracy, goes as far as to proclaim that “President Summers had messed with the wrong Negro.”

Summers has repeatedly refused to comment on what transpired between him and West on the grounds that he does not discuss the content of any meeting with Faculty members.

“I have not talked about the content of that meeting and certainly do not intend to start now,” Summers said in Oct. 2002. But he has said that he made efforts to broker peace with West before his departure and convince him to stay at Harvard.

West addresses the Summers dispute within the larger context of the obligation of intellectuals and professors to go beyond the ivory tower and engage with the democratic community as a whole. His critique of Summers is framed within a larger criticism of “the technocratic management culture on the rise in our universities today [that] offers few…democratic rewards.”

West’s discussion of his dispute with Summers is particularly timely because tensions between Summers and the African and African-American Studies Department resurfaced recently when two Harvard Af-Am professors, Lawrence Bobo and his wife Marcyliena Morgan, announced they will leave Harvard at the end of the fall semester to take up tenured positions at Stanford. Their departure has been attributed by colleagues to the fact that Summers denied Morgan tenure at Harvard this past summer.

West says this incident is part of a larger conspiracy by Summers and others at the University to diminish the standing of black professors at Harvard.

“Summers and others were deeply upset that black professors were becoming the public face of Harvard…and so we’ve seen a set of actions that at this point are pretty undeniable that ensure that those black public officials are put in their place,” West says in an interview the day after his speech.

But W.E.B. DuBois Professor of the Humanities and Af-Am Department Chair Henry Louis Gates, Jr. says that significant tension between the department and Summers are non-existent.

“We have a wonderfully warm, direct and honest relationship,” Gates said in September after Morgan and Bobo announced their imminent departure. “While we do not always agree, I believe that we respect each other’s opinions.”

It seems as if West may forever be associated with his row with Summers, just as that row at times distracts from his scholarship in Democracy Matters.

But for West, no matter what his relations with the President, they will not cloud his feelings for his alma mater.

“Cambridge is a home among other homes,” he says. “I wish the school well, I wish the Harvard tradition well.”

—Staff writer William C. Marra can be reached at wmarra@fas.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.