My Left Hand

The Shakespeare and Company Bookstore, located on the Left Bank of the Seine River in Paris, has seen many an interesting traveler in its day. Historically associated with great writers such as Ernest Hemingway and James Joyce, the store is filled with beds where writers and artists can live in the shop at no charge. Their only obligations are to tend to the shop for an hour a day and read one book a day. Bohemians and counter-culture rebels have for many years passed in and out of the shop in their quests for enlightenment and artistic expression. Last month, they bunked with a linebacker.

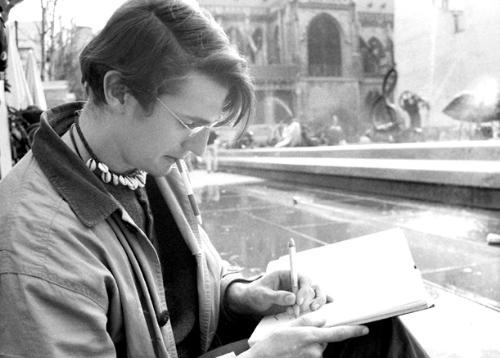

Robert Schaffer ’05, a former member of Harvard’s varsity Football team, spent a few nights at the Shakespeare and Company, but left after three days because he found the environment “not conducive to a painter or visual artist mind set.” The former Crimson linebacker quit the team in January and withdrew for the semester in early March, having decided to head to France to immerse himself in the Parisian art scene and explore his artistic potential.

An intimidating specimen at 6’2”, 200 lbs., Schaffer’s exterior is belied by his goofy confidence—part star athlete, part class clown.

“He’s a very endearing guy with a wildly outlandish spirit,” says former teammate and friend Conor G. Black ’04. Since he became an artist, Schaffer has found a creative outlet for that spirit.

“Art cannot be anything but personal,” he says. “I am an extrovert and things are always coming outwards. The energy is exothermic. This helps with art because you are trying to take all of the emotions that you are feeling at the time and manifest them into something like a blank canvas or a blank piece of paper.”

Schaffer may sound like he’s been an artist all his life, but until recently, football was his most serious passion. He was recruited by Harvard in 2001 to play tailback, but was quickly converted to outside linebacker and then to middle linebacker.

“[He’s] a high energy guy, very competitive and a good kid,” Harvard Football coach Tim Murphy wrote in an e-mail. “[He has] good size, speed, [and he] enjoyed contact. Like many young players, he was still trying to find the best position for him.”

Schaffer did not receive extensive playing time but was recognized for his hard work and competitive spirit.

“Rob had a good work ethic and was a very enthusiastic practice participant,” Murphy says. “My expectations of all young players are that they will work hard, compete, make friends and learn some life lessons through participation in intercollegiate football. Beyond that I felt that Rob had the potential to compete at this level by his senior year.”

Schaffer was one of a half-dozen-or-so first-years to make the traveling squad in 2001, and as a sophomore, he got into several games on special teams. Nonetheless, he felt disillusioned by his football experience and quit the team in January.

“I quit football because I could not handle the rigid social hierarchy that came with it,” Schaffer says. “The game of football still thrilled me but those who I had to pass through in order to attain my thrill lacked a true understanding of my personality, and were incapable of coaching me.”

Schaffer made a swift transition to art, perhaps eased by his exposure to it at a young age. His mother was a middle school art teacher, and familiarized Schaffer with Renoir, Manet, and Cezanne. Schaffer says he came to view art quite narrowly, as a combination of landscapes and portraits, and decided to pursue athletics.

Growing up in a suburb of Chicago, Schaffer says football was the accepted path, an endeavor that earned him the respect of his community and his peers. “I felt the weight of my societal baggage,” Schaffer says.

Nonetheless, Schaffer found his creative outlet at tailback. “The position allowed me the most creativity possible on a football field,” Schaffer recently wrote in a grant-application essay. “Once the ball was handed off to me I was free to create my own destiny. It was my own world to fashion.”

At Harvard, however, Schaffer found the football program too regimented for his liking. “Football in a college setting…is more like the military,” writes Schaffer. “There is a strict chain of command in its arrangement of both players and coaches. Players report to position coaches, who report to offensive or defensive coordinators, who then report to the head coach. All orders are to be followed eagerly and wholeheartedly, with little room for dissent.”

Schaffer had always been somewhat distant from the football scene. Unlike most players, he did not block with any of his teammates. He was always an extremely hard worker, but he was unwilling to sacrifice his individuality to the team.

“I stopped playing because I found myself no longer able to suppress my creative capacities,” he writes in an e-mail. “I needed to leave football’s system behind in order to create a new system which I will dictate myself.”

Schaffer’s discovery of art, however, occurred before he officially quit the team. One December night, while hanging out with friends in Dunster House, Schaffer began doodling.

“He’d sit right here,” says Thomas J. “T.J.” Scaramellino ’05, pointing to a chair by his desk. “He’d get a paper and this clipboard and he’d take this light, and shine it as bright as possible on the clipboard and just sit here and shake his knee really fast, really jittery for about six hours straight and not get up.”

The experience was surreal for all those involved.

“According to [Schaffer], what he was doing wasn’t drawing,” Scaramellino says. “What he was doing was looking at the way the light hit the paper and the paper would show him images. He was just tracing the images that he saw come up from the light on the paper. He felt that he was just the receptacle of this divine communication that he had access to.”

Schaffer had not taken an art class since eighth grade, and says this was the first time he ever seriously attempted to express himself visually. His earliest work was primarily scribbles with pen on pieces of paper.

“This is just me, for the first time, finding that I’m able to see things in the paper,” Schaffer says of his first piece. He spent the next month and a half drawing as much as possible, quickly showing improvement. Though his art remained extremely abstract, distinct images were clearly visible in his work.

“What he showed in [in that time] was an immense amount of progress.” Scaramellino says. “At first, we thought it was a joke. We thought it was a withdrawal thing from football, but with the progress he showed, we were like ‘Go for it, Schaffer.’”

Schaffer soon switched concentrations, from Social Anthropology to Visual and Environmental Studies. That change, however, was not enough to satisfy his newfound passion. He officially quit the football team in early January, and by the end of the month, he had decided to withdraw for the semester and travel to Paris. He officially withdrew on March 5.

In early February, Schaffer drew a picture titled “Cocoon Me.” On the right side of the page there is a strange, alien figure. Merging with this figure on the left is a butterfly in full flight. “It was a ‘foreshadowing’ picture,” Schaffer says.

A week later, Schaffer says, he had a creative breakthrough. While working on a painting, he suddenly drew a line in the middle of the canvas. Until that point, the right-handed Schaffer had been painting on the right side of the canvas, with his right hand. Mid-painting, he switched to his left hand and began forming bizarre images of faces, people and animals. He has not painted with his right hand since.

Despite his 21 years of right-handedness, Schaffer now believes that he has always been “naturally” left-handed. “I think it’s without question that my left hand is more deft, more expressive,” he says. Schaffer took to drawing with his left hand even more seriously than he had with his right.

“For about a week and a half, that was the only thing he talked about,” Scaramellino says. When Schaffer told his friends of his plans to go to Paris, he received mixed reactions.

“The reception among our friends was ‘He’s probably crazy, but that’s alright,’” Scaramellino says. “Let him be crazy. Let him to do what he’s got to do. If this whole thing doesn’t work out for him he can always come back.’”

Schaffer’s Harvard friends are not the only ones who have supported his artistic development. As a member of Harvard’s chapter of the Pi Kappa Alpha (Pike) fraternity, Schaffer made a lasting impression on Bruce Wolfson, a New York based lawyer and the fraternity’s international vice president. Schaffer and Wolfson worked together on the Pike’s “Return to Values” initiative, a campaign which sought to reinstill the fraternity with a spirit of brotherhood and to encourage its members to give back to their communities.

“As we talked, it was clear that the same part of [Schaffer] that found the ‘Return to Values’ initiative so appealing—because it was a spiritual undertaking—was driving his decision to go to Paris and pursue art,” says Wolfson.

Before leaving for Paris, Schaffer visited Wolfson in New York to show him his work. Though Wolfson has no formal training in the arts, he thought he saw potential in Schaffer.

“He has the ability to draw things that are recognizable and representational,” Wolfson says. “He’s also able to use symbols, combine a number of complex themes.” Wolfson also noted the expressiveness of Schaffer’s left hand.

“His art with his left hand is extraordinarily personal and private,” Wolfson says. “It’s more intimate drama, the essence of who he is. It is a freer expression of what’s inside.”

Now back in the Boston area living with his brother, Schaffer remains obsessed with art, and is making plans to return to Paris this summer. Football seems like a distant memory. He still runs and does muscular exercises, but he as decided to give his body a rest from heavy weightlifting.

“I do not think about returning to football because it is a life I know well,” Schaffer says of the possibilities of a comeback.

But, Schaffer concedes that there is a void to be filled in his creative spirit since leaving football.

“I miss the intense connection that is cultivated between people with 35 hour workweek in season,” Schaffer says. “But instead of this intense connection in a football setting, I will hopefully have these type of relationships in a different context.”

If Schaffer’s left hand is involved, that context is sure to be a colorful one.