On The Polish Question

Harvard attracts some big name speakers, giving students the chance to hear international luminaries, behind-the-scenes politicos and literary giants share their thoughts on the world. But what about seeing someone who, despite having earned international fame, still feels like a kind of homegrown hero?

“He isn’t exactly an educated man,” Wojciech Kubik ’07 reluctantly says of his birth country’s modern emblem, Lech Walesa, who spoke to a packed house at the Institute of Politics last week. “He is idolized [in Poland],” Kubik says, “he’s idolized, though not as much as in the international community.” Kubik, whose family sought refuge from Communist Poland in 1987, has seen his life intertwined with the political ascent of Walesa. Kubik’s parents escaped the disappointment of showing up at a supermarket and discovering only tea and vinegar on the shelves, Kubik says, by emigrating to the United States. His great-grandfather disappeared at the hands of the Communists, and his grandmother was present at the shipyard riots.

Walesa, for those who have forgotten the timeline of the USSR’s fall, worked in the Gdansk shipyards when Poland was still a Soviet satellite state. He became famous organizing labor into the Solidarity union, after he took part in the Gdansk shipyard riots in 1980. Solidarity was the first labor union of its kind in a Communist country, gaining millions of supporters. For his work he received a Nobel peace prize in 1983, and is widely credited with helping to break down the Soviet system in Poland. When it did finally fall, Walesa was elected president in 1990, though not reelected in 1995.

“His education is that of an electrician. And then he formed the union…and then was pulled into the government,” Kubik says. “During his presidency the complaint of a lot of Polish people was that his speeches were a little less than eloquent. When he was addressing the UN and the president of the United States, Polish people would be watching TV like, ‘Oh My God! What are you saying!’ Because a lot of his colloquialisms are, well, I hate to break Poland down into classes, but they were working class colloquialisms.”

Which may be why Kubik opted for a different line of questioning last week. When the commanding, moustached former president yielded the floor to questions—after a 30 minute speech railing on the sloppiness of American foreign policy—Kubik was one of the few audience members who didn’t ask about the nature of communist economic oppression, the daunting tasks facing China when (and if) it makes the switch to a capitalist system, or Brazilian labor leader-turned-President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. No, Kubik went for a more specific topic.

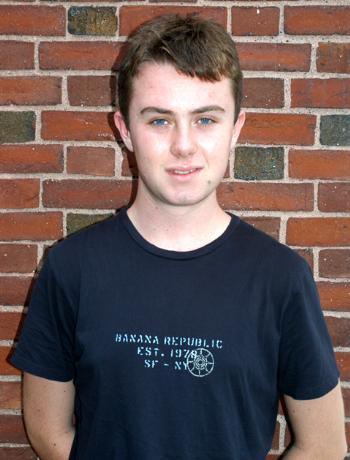

Dressed in a black button down and khakis, Kubik, who speaks without a trace of a Polish accent—though with a hint of Addison, Illinois, the suburb of Chicago where he now lives—addressed the audience in English and Walesa in Polish, asking him about coal mines in the country. The mines’ workers, finding themselves out of work and now faced with a supply-and-demand economy and not all that much demand, have attacked the economic policies of the current government.

“I didn’t get too clear a response. He commented on how that came to be, but it didn’t say how to solve it,” Kubik says, slightly disappointed, though still appreciative of the chance to ask Walesa a question face-to-face.

Kubik, who arrived in Chicago in 1987, when he was not yet three years old (one of his first memories, he says, was seeing the black and white checkered floor of his grandmother’s basement, where he and his parents lived for three years after emigrating) has seen Walesa before. About five years ago, Walesa spoke in Chicago, though in a setting very different from the IOP forum. He spoke then without a translator, addressing a crowd of locals gathered in the neighborhood Polish Catholic Church. (“Chicago has as many Polish people as Warsaw, I think,” Kubik says. He’s almost right: Warsaw has a population of about 1.6 million and Illinois a Polish population of about 950,000.)

What of seeing the man here in the U.S, in this setting? “It was interesting to see him in the elevated context,” Kubik says. “It wasn’t necessarily a bad thing to see him here but it was weird to see him…because it was sort of different from the general Polish ideal of who he is.”