News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

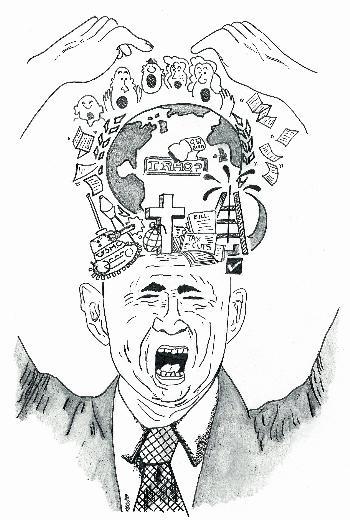

Is the U.S. Heading Toward Withdrawal From Iraq?

A collision may be looming as the U.S. position in Iraq devolves and the U.S. presidential election evolves—a forbidding confrontation of foreign policy and domestic politics.

The question is whether the U.S. will continue its rallying cry for a viable effort in Iraq or instead lower its voice to a whimper, foreshadowing a muffled withdrawal from its current commitment. Do we have a serious, reality-based strategy capable of moving events in Iraq in our favor, or merely an incrementalist, catch-up mentality which will ultimately prove its own insufficiency?

The Bush administration recently submitted to Congress a request for $87 billion to cover a complex mixture of security and reconstruction costs over the next fiscal year. This was accompanied by tough and stirring words stressing the U.S. plans to follow through on security, reconstruction and nation-building challenges related to its war on terrorism. Such rhetoric was necessary not only to provide credibility to the request, but also to shore up the administration’s declining fortunes both in Iraq and the U.S., and to reassert its aggressive, hegemonic national security strategy abroad.

But despite its bold posture, there is a foreboding of factors and developments which the Bush administration faces regarding Iraq—many of which lie beyond its control—that, taken together, could tempt a radical policy change. This could happen as a consequence of cumulative events producing an irresistible momentum over a period of time rather than by way of a deliberate, explicit political decision.

First, there is at least an uncertain and unstable and at worst a desperate and deteriorating situation on the ground in Iraq: guerrilla war; unguarded munitions and missing missiles; inadequate security personnel; a continuing death toll of U.S. soldiers; an assassinated member of the Governing Council; opposition to the occupation from the general population in the absence of services, utilities and jobs; barricaded offices and restricted mobility which contribute to stalemated reconstruction; the absence of U.N. and NGO humanitarian and development workers; hostility and jockeying among differing indigenous, ethnic and political groups.

Moreover, pressures are mounting to quicken the pace of nation-building—but they are not consistent with ensuring a reliable and lasting result. The Security Council, our allies and the Iraqis themselves are producing a cacophony of demands to turn over authority in both the military and civilian arenas to the U.N. and to the Iraqis in various competing configurations. It is ironic that while the U.S. is correctly resisting this particular ‘hurry-up’ trend—rightly arguing that the legitimacy and capacity of the Iraqis needs more time to be developed—the French are clamoring for the conferring of authority on an Iraqi Governing Council which was totally hand-picked by the Americans. Some Iraqi leaders are even asking to be given principal domestic security responsibility without delay. At the same time, almost immediately following the setting of a six-month deadline by the U.S. for constitution preparation, the Iraqi committee charged to recommend a procedure for this announced that wrangling among its various factions had stymied consensus.

Next, there is to be a dearth of resources to devote to the cause: efforts bilaterally and at the U.N. to persuade other nations to contribute cash and troops have fallen short; Congressional approval for the new aid request on top of money already spent, are under increasingly alarmed scrutiny especially in the face of predictions of greater expenditures to come; and U.S. troops are stretched so thin that rotations are delayed, more Reserves and National Guard must be called up and the Marines have been asked to forego their classic expeditionary mission in favor of stabilization tasks.

Finally, here at home there are additional factors that could threaten a long-term U.S. commitment to nation-building and stability in Iraq. Long since the president’s announcement that the war-fighting was over, American soldiers have continued to die in Iraq on a daily basis; public discouragement increases over the uncertainty and dislocation of extended periods of service of our soldiers and reserves; an “infrastructure vs. infrastructure” controversy has emerged over concerns that money being requested for Iraq is not available for urgent unfunded needs at home; the schism between high expenses of an assertive foreign policy and domestic tax and budget cuts is becoming more palpable; and public opinion polls have begun to reflect skittishness about the U.S. role in Iraq and a softening of the president’s popularity.

As the 2004 election approaches, the White House will especially want to avoid getting into more trouble in Iraq and projecting images of confusion and faulty leadership in foreign policy. It is premature now to predict that in order to head off these dangers it will choose pulling back over pressing ahead—we could get our act together, and things could start to break our way. But the aggregation of incentives to pull back enumerated above is already formidable. A decision to back off—whether intentional or by default, whether by declaring victory or by palming the job and the fault off onto others abroad and at home—could make our hasty exit from Somalia look like grace under pressure. Our respect and influence in the world, our ability to pursue our interests globally in prudent and effective ways, would be greatly damaged; further harm would come to the Iraqi people and bedlam to the Middle East; and the blame would be placed on us—abroad and at home.

What changes in U.S. policy toward Iraq, while unfamiliar to the White House and painful to swallow, would constitute a strategy with a good enough prospect of eventual success so as to head off the option of copping out? While there are no policy changes that can avoid peril, this is the jam that we’ve gotten ourselves into, and sticking to the current scheme courts disaster. There are several components which might constitute a strategy worth pursuing.

One, security throughout Iraq must be effected now. This will require more troops to cover the country, both foreign and American. The U.S. position of being only willing to use foreign security forces to replace our soldiers, thus not committing any more of our own and not increasing the total number, will have to be given up. Training and deploying Iraqi military and police too quickly is dangerous. Even so, the resulting need for U.S. troops would be less than if we failed to attract international peace-keeping cooperation. A U.N. Security Council endorsement and umbrella could be helpful to this end, but the U.S. must keep the command authority over the troops.

Two, the U.S. should turn over its responsibility for running the civilian effort—this means humanitarian aid, rehabilitation and reconstruction, and nation-building programs—to the U.N., while, maintaining strong, active participation and support. The U.S. must remember after all, that it is the most important member of the world organization and that our role will be essential far beyond protecting the continuity and momentum of what we have already undertaken. The U.N. offers no panacea, indeed it is rife with limitations and flaws, and is a risky bet for running the show. But what we are dealing with here is an enormously problematic challenge and there is no way to do it well or to guarantee success. The point is that the U.N. is more likely do it better than the U.S., with more experience, broader mobilization and a longer-term commitment, while attracting more cooperation and less suspicion and enmity. Its weaknesses will be less consequential and more tolerated than ours.

Three, the U.S. should hold fast to its position that responsibility in various sectors not be turned over to the Iraqis prematurely, before the capacity has been properly prepared, and before the political context is stable and coherent enough. No one disagrees that the Iraqis must run their own country and affairs, but those inside and outside Iraq who are lobbying for a quick turnover are naïve or self-serving. There is no instant capacity or democracy here. This transition is terribly delicate. If it is not pursued painstakingly and patiently, it can contribute to more chaos and disunity rather than defeating those foes. If, however, efforts are undertaken with true collaboration with and close reliance on the Iraqi authorities, clearly progressing toward their takeover, agitation to get rid of the occupiers fast will diminish.

Four, the Bush administration needs to undertake a serious educational campaign within the United States, putting aside jingoistic slogans and intimidations and setting forth soberly and straightforwardly its perception of the stakes, realities and costs involved so that the citizenry can better understand and judge. We do not currently have a thorough public consideration about Iraq engaged in this country, and this is sorely needed if we are to be able to exercise the opportunities for self-government especially prevalent during a presidential election campaign.

Without a shared competence abroad and an informed and supportive consensus at home, we stand perilously close to sacrificing the awesome responsibility we have assigned ourselves in Iraq.

Jonathan Moore was director of the Institute of Politics from 1974 to 1986 and subsequently served as U.S. Coordinator for Refugees and as Ambassador to the United Nations. He is currently an advisor to the U.N. Development Program and an associate at the Shorenstein Center for the Press, Politics and Public Policy at the Kennedy School of Government.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.