News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

Harvard's Crimson Scare

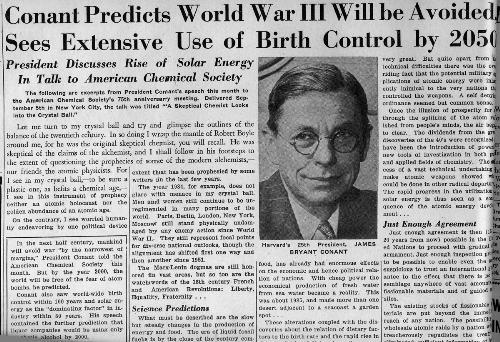

A president defends the University as accusations of communism fly

On Oct. 15, 1951, the Massachusetts state legislature passed a bill making university presidents responsible for preventing communist and subversive activities from taking place on campus.

The new law launched an offensive on the principles of academic freedom long cherished by students and faculty and illuminated a long-time dilemma at Harvard—what was the University’s proper role in the all-encompassing fight against communism?

The looming threat of Stalin’s Soviet Union overshadowed campus life during the Class of 1952’s senior year, as the merits of academic freedom became an almost daily subject of debate and prominent professors faced allegations of treachery.

Leading the University was eminent chemist and erudite political commentator James Bryant Conant ’14, who in the last year of his presidency sought to pilot Harvard through this period of turbulence.

“Drastic shifts in the national scene,” he wrote in his final presidential report at the end of the academic year, “have influenced immediately and profoundly the work of all our major institutions.”

The dangers of the nuclear age were a constant preoccupation during the year, as Harvard faculty and students worried along with the rest of the country about the dangers of mutually assured destruction.

Seeking to underscore the dangers posed by the Soviet Union, Conant brought the prospect of a nuclear holocaust closer to home.

“The prospect of the physical annihilation of all of Harvard is for the first time in all our history a possibility we must admit,” he wrote.

As it had provided technological expertise in the Second World War just a decade previously, Harvard now offered its country ideological support for the battle against communism.

So much was even noted in Moscow. The Russian humor magazine Krokodil lambasted Harvard in its Sept. 30 edition for being under the thumb of the U.S. military. It even ran a cartoon on its back page entitled “Mathematics,” which showed a drill sergeant shouting “one, two, one, two” at a group of Harvard students carrying rifles.

‘Period of Trial’

Although Soviet critics viewed Harvard as a bastion of right-wing militarism, many in America worried about its spiritual collapse under a socialist threat.

The editor of a reactionary monthly magazine, The Cross and the Flag, accused the president of the Harvard Liberal Union, Walter C. Carrington ’52, of being a “creeping socialist” and demanded that he be expelled.

Meanwhile a string of Harvard professors found themselves charged as communists and fierce debate raged in Cambridge—as it did nationwide—on the boundary between protecting academic freedom and preventing treason.

Conant sided clearly in favor of openness and academic freedom, which he said constituted “the essence of a university.” Nonetheless he acknowledged that America found itself undergoing “a long period of trial for the university tradition which started when Hitler came to power in Germany.”

A number of Harvard faculty members attacked the so-called “anti-subversive bill” that had passed the State House in October. The bill, they claimed, restricted academic freedom while remaining largely inept at tackling the genuine dangers posed by communism.

Speaking for those who feared encroachment on the principles of academic freedom, Samuel H. Beer, associate professor of Government, dismissed anti-subversive bills as mere publicity stunts by over-zealous lawmakers.

“They’re pure demagogy,” he said one evening at a Harvard-sponsored discussion, “aimed at trying to get votes and hitting the headlines. They have no utility value or need at all.”

More than 1,000 Harvard students agreed, signing a petition organized by Carrington and his prominent Liberal Union to protest the Massachusetts bill. Carrington described the measure as “unconstitutional and unnecessary in that the threat which it tries to meet has been over-exaggerated.”

The Crimson’s editorial page added its support, charging that the bill displayed “unprecedented naivete and illogic” and would force colleges to “operate under an atmosphere of fear and suspicion.”

Over their protests, Governor Paul A. Dever signed the bill into law on November 17.

Reds All Over?

The Cold War was at the forefront of many Harvard minds, not least because eight percent of the University’s financing came from government research contracts.

In contrast to Harvard’s tremendous involvement in the Second World War, when the University was involved in vast confidential research projects, participation in the struggle against Communism was piecemeal and fairly small-scale.

That year saw the Business School finally end its classified government experiments, seven years after the end of the Second World War.

Conant had taken a leave of absence from Harvard during the Second World War to personally contribute to J. Robert Oppenheimer’s ’26 Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, N.M., which led to the development of the atom bomb.

But in 1951-52, Conant was ensconced in Loeb House in 1951 to oversee the Harvard administration.

At the same time as Harvard scaled back its contribution, members of the Faculty found themselves unwittingly drawn into the conflict.

Several professors stood accused of having personal communist connections. Most prominently, Professor of History John K. Fairbank ’29 was not initially allowed to take a year’s sabbatical leave teaching in Japan because of supposed communist links.

Fairbank was accused by confessed ex-communists Elizabeth Bentley and Louis Budenz before the House Un-American Activities Committee of having had ties with the party. Although the Department of the Army did lift his travel restrictions in the spring of 1952, Fairbank was repeatedly attacked by critics as a communist sympathizer.

The ramifications of having tainted men on the faculty were tremendous.

Self-proclaimed “Redbusters” attacked Harvard, protesting that innocent students were being indoctrinated by dangerous left-wingers.

McGeorge Bundy, future dean of the Faculty, as well as national security advisor to Presidents John F. Kennedy ’40 and Lyndon B. Johnson, was then associate professor of government and engaged in almost weekly debates on the merits of academic freedom and foreign policy with prominent visitors and fellow faculty members.

Others, however, feared engaging communism head on.

Edward S. Mason, Baker professor of economics, publicly declined an invitation from a Polish economist to attend a Moscow conference on world trade, saying he feared its intellectual basis and free discussions would be undermined by the presence of delegates from communist countries.

The impact of the Cold War was even felt among Harvard’s non-academic personnel. In November 1951 William J. Bingham ’16, a former director of athletics, suddenly resigned as chair of the Faculty Committee on Athletics in order to accept a position in what he termed “vital defense work” in Washington.

Bingham had served as a director of security and intelligence for the federal government during the Second World War, and now he shifted within a matter of weeks from organizing intramural athletic events at Harvard to a full-time job in national defense.

Bully Pulpit

In his final year in office, Conant was particularly outspoken about foreign affairs.

Conant was a nationally known figure. In late 1951, he ran fifth behind General Dwight D. Eisenhower in a poll of potential Republican presidential candidates.

He used his stature and prominent position to prognosticate frequently—and presciently—about the future of the Cold War. He correctly foretold that there would be no Third World War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union but that the conflict would instead play itself out in a series of “short local wars.”

Conant also accurately suggested that arms decommissioning would begin in earnest in the 1970s.

Before then, however, he advocated a strong U.S. foreign policy to counteract the Soviet threat.

“The rearmament of defense of Europe is the only way out of the atomic age,” he told students at the Law School on Oct. 16, 1951. “Once Europe is stabilized we can talk about taking bombs out of each others’ houses.”

A fervent believer in the important roles universities had to play in such a conflict, Conant concluded his final presidential report with a ringing endorsement of the value of higher education to democratic society.

“As vital centers of sound learning, as strongpoints defending individual liberty, as communities of creative thinkers, no industrialized democracy can do without them,” he wrote. “Each year will demonstrate their indispensability to this society of free men.”

—Staff writer Anthony S.A. Freinberg can be reached at freinber@fas.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.