News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

Making Our Education Whole

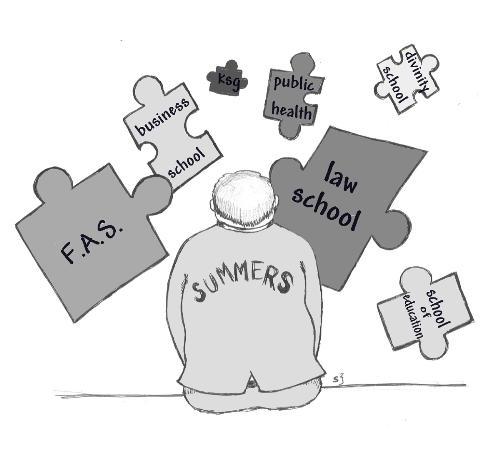

University is from the Latin universus meaning whole. However, Harvard’s familiar mantra of “every tub on its own bottom” fragments the University and exacerbates the lack of interaction among the students and faculty of its several schools.

Although decentralization provides autonomy to the various schools, it detracts from the wholeness that should be the true meaning and mission of a university. When the challenges facing society increasingly require multidisciplinary approaches, it creates artificial boundaries between disciplines and reinforces the idea that cross-disciplinary studies are not valuable.

While faculty and students at Harvard can and do transcend boundaries between disciplines, they almost always do so as part of grass-roots movements that prioritize the value of learning from colleagues at all of the schools. Although both University President Lawrence H. Summers and Provost Steven E. Hyman have emphasized, through interfaculty initiatives and public statements, the need for more cross-disciplinary efforts, a larger commitment is needed.

One example of grass-roots efforts aimed at addressing the downside of decentralization is the Harvard Health Caucus at Harvard Medical School (HMS), an organization of graduate students that I founded during my first year as a student in HMS. Its purpose is to encourage students from the various graduate and professional schools to meet and discuss issues in health policy. The centerpiece of the Caucus’ activities is a yearly Policy Roundtable Series, where we focus on one topic over a period of months and hold panel discussions at the various Harvard campuses.

Last spring, we focused on the social implications of the Human Genome Project and held in-depth sessions on genetic privacy, the doctor-patient relationship, the role of the media, commercialization of the genome and the perspective of various religious disciplines. These sessions brought the Law School, the School of Public Health, the Kennedy School of Government, the Business School and the Divinity School together with HMS. This year, we tackled the impact of globalization on health, including a panel on the relationship between health and economic development at the Kennedy School and a panel on creating incentives for research and development of medicines for diseases in developing countries at the Harvard Business School.

But such interdisciplinary collaboration is far too rare. Think of some of the great challenges facing society today and consider what kinds of experts you would want developing public policy aimed at addressing these challenges. It’s likely that a blue-ribbon panel on economic development or bioterrorism would include economists, public health experts, environmental engineers, sociologists and management experts among others.

Because important policy questions require common ground among people representing different fields, it is essential that the University encourage cross-disciplinary dialogue.

Harvard is the ideal place for students of management to begin to understand the concerns and vocabulary of physicians and for public policy students to familiarize themselves with the viewpoints of public health students. Cross-disciplinary studies reinforce the contributions of other professionals and sensitize us to the value added to a Harvard degree by a more rounded view of the world. This is not to say that curriculum should become less rigorous; on the contrary, cross-disciplinary studies recognize that a single-minded approach to any problem is likely to be inadequate.

So how can the University foster the kind of cross-disciplinary efforts that would make a Harvard education “whole”? The initials steps require administrators from each school to acknowledge the value of cross-disciplinary work and to create an atmosphere conducive to such efforts. By focusing support on existing efforts at the faculty and student levels, and by highlighting the potential for new inter-school collaboration, the administration would signal its desire to cultivate interdisciplinary study.

From there, the University should proceed by removing some of the bureaucratic hurdles that face both students and faculty. Examples of how the bureaucracy of decentralization stymies cross-disciplinary studies abound: the cross-registration process is inefficient, there is no centralized calendar of events for all schools, the schools are on different academic schedules and combined degree programs are often an administrative headache for students. The University should align the academic calendars of all of its graduate schools —or at minimum, put all classes on the same time schedule. It should reduce barriers to cross-registration, allow cross-registration on the web and publish a centralized calendar of events at Harvard, searchable by topic, and available to all students and faculty on the web. This infrastructure, along with a strong commitment to promoting cross-disciplinary exchange, is essential for equipping Harvard and its graduates with the tools necessary for the most perplexing problems of today and tomorrow.

Erica Seiguer is a third year MD-Ph.D student at Harvard, currently in the Doctoral Program in Health Policy.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.