News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

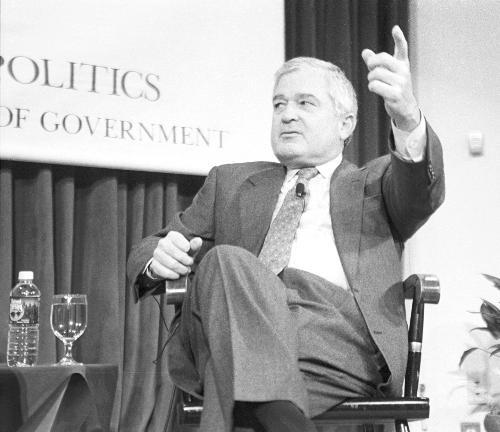

Former IBM Chief Shares Rescue Recipe

Skip the vision statement.

Create a sense of crisis.

Change the “old-world” dress code.

These guiding principles led IBM from near-bankruptcy in 1993 to an over $85 billion corporation today, said its former CEO Louis V. Gerstner Jr. last night at the Kennedy School of Government’s ARCO Forum.

In an event revealing Gerstner’s recipe of rescue, Director of the Center for Public Leadership David Gergen touted his guest’s “inspiring leadership and vision” to a crowd of about 250.

When Gerstner accepted the top job at IBM a decade ago, the media and company insiders were speculating about his new mission statement for the ailing information technology firm.

“[But] if I came in with a vision, it would just give them another six months to debate about the vision, but we had to work fast,” he said. “We were running out of money.”

Instead of catering to the individual demands of 30,000 staff members—including “more Nobel laureates than most countries”—Gerstner flouted tradition and made important decisions himself in his first 100 days.

Notably, he reversed a plan to break up IBM into smaller companies, which he said was the most important business decision he has ever made.

“I really don’t think that there would be an IBM if it was split up,” Gerstner said. “Some of the media thought that I really lost my mind, but [thinking] as a customer, it was an easy decision.”

He lowered the cost of IBM’s mainframes, and there has been an annual price cut ever since.

“What I brought to IBM was the voice of the customer,” Gerstner said.

He brought the customer’s clothes as well.

After decades of blue suits, Gerstner said he relaxed the dress code so that employees could wear blue jeans.

He credits much of his success to connecting with people on a human, not corporate, level.

“Who wants to work for a Wizard of Oz who bangs on the drums and decisions come out?” Gerstner asked.

In order to get his employees to start thinking the same way, he changed the compensation system to make salaries dependent on team, not individual, performance.

Previously, “it was every man, woman and child for themselves,” he said. “People could be making lots of money while the company could be floundering.”

This approach is a refreshing exception to the prevalent corruption in corporate America, Gergen said.

Yet one audience member questioned whether Gerstner’s resuscitation of IBM merited a reported $14 million-a-year salary.

“There are too many people paid lots of money for no performance,” said Gerstner, asserting that his triumph involved the highest of stakes.

“IBM is a national treasure,” a Nobel laureate once told him. “Don’t screw up.”

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.